How Egyptian Women Illuminate Ancient Wisdom

When French sculptor Bartholdi chose an Egyptian peasant woman (fellah) as the design for the canal in Egypt, which was rejected, just a year before he submitted his ideas for the Statue of Liberty, he was unknowingly selecting a figure who embodied thousands of years of preserved wisdom. Winifred Blackman's 1927 study of Egypt's rural fellahin communities reveals that these women, especially in Upper Egypt (where Bartholdi described his inspiration), maintained ancient traditions virtually unchanged since pharaonic times—from their reverence for motherhood that echoed goddess worship, to birthday celebrations with candles that honored the sun god Re, to baptismal rituals using sacred waters that mirrored both ancient rebirth ceremonies and the life-giving waters of the womb. These communities preserved spiritual practices where Christian and Muslim saints often concealed ancient Egyptian deities, particularly female ones, creating a living bridge between humanity's earliest understanding of the divine feminine and modern religious expression. The fellaha that inspired Lady Liberty represented not just an Egyptian peasant, but a universal symbol of women as keepers of sacred knowledge—those who preserve the light of wisdom, protect their communities like divine mothers, and maintain the spiritual connections that transcend individual religions to touch something deeper about human experience itself.

The Eternal Mothers: How Egyptian Fellahin Women Illuminate Ancient Wisdom and Modern Faith

When French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi first envisioned a colossal lighthouse for the Suez Canal in the 1860s, he drew inspiration from an unlikely source: a female fellaha—a simple Egyptian female farmer, what google will call “a peasant woman”. Though that project never received funding, the image of this Egyptian woman carrying light would soon transform into Lady Liberty herself, gifted to America as a symbol of freedom. But what did Bartholdi see in these rural Egyptian women that so captured his imagination? The answer lies in a remarkable 1927 study from one of the first female researchers in Egypt, looking at the people and culture to reveal these women as living bridges between ancient Egypt and the modern world.

My Interest and Goals for the Study

Winifred gives us insight into her work, and reminds us the importance of a woman’s perspective on this kind of research. She was able to enter communities that were not open to men. She cared about poor people, and lived among them, while most would try to look away. She was one of the first people to gather ethnographic data in Egypt (the study of people), with notes, photographs, drawings, even some film. She was able to watch rituals from tattooing to birth and naming ceremonies. She spent 6 months at a time, for 6 years straight, not among the pyramids, but within the smaller communities in Upper Egypt (the southern, more ancient portion). She was interested in people AND science, gaining respect in both fields.

Before even starting this research, I wanted to know what the term Fellah meant, the term used by Bartholdi, specificlaly pointing out those of “upper Egypt”. This was one of the best sources on the topic. Google’s first definition was that of a “peasant Arab woman”. And immediately, I feel the tinge of, eh, alright. Even though I love plant studies with other women, like Jane of the Herbs, who spent her days among peasants of Russia to learn their ways and methods and childbirth, I still had the feeling of, oh, time to move on to more important things. My pull to dismiss them was a fraction of a second before I caught myself, but it was there. google searches call her an Arab peasant. This is a highly incomplete and almost innacurate statement to leave it like that. She was an egyptian woman, who worked the land like her family had done for generations before anyone from the outside came in. She may now be arab, but we also see a different kind of religion than just a convert, we see older traditions preserved by necesity with a way of life that essentially would have stayed the same and be quite different even if she had been forced to convert to another religion or not. the term should be egyptian fellah. Her religion seems irrelevant and misleading. most of the women in egypt, after many years of conquest, often stayed and maintained older traditions, while men faught and were pushed out. In many religions, jewish included, children inherit the religion of the mother (by default). We can learn quite a bit by studying them, knowing few would care too much to study them, especially to live among them.

I wanted to know more- maybe they preserved something there. And what was it that Bartholdi saw in them? Me, an engineer, mom and herbalist is deeply interested, but what about a man in the early 1900’s, a 19 year old painter who, upon seeing the colossal statues in Egypt decided to become a scultor instead, changing his career path entirely. Within 10 years, he wanted to build a statue of one of these women, a simple woman, not a goddess. An Egyptian woman. Not a mother, a human. Not only for her sensuality or productivity, but just being herself. Within a few years, this morphed into an idea of the Statue of Liberty. Not just a discarded idea, but one he wanted to see finished- a woman, as a symbol of freedom and enlightenment.

What were these women like? Would he have bumped into them in the market? Winifred was doing her study around the same time: Bartholdi in 1855, Winifred in 1920’s, so about 75 years later.

How were simple women treated then, and how were they treated in the times of the Pharoahs, when Egypt was at the height of its power? How did her role change under foreign rule, then as Christians then Arabs came through?

Preface for the Fellahin Study

In Winifred’s preface to her book, she mentions she was not done. She still had many years of research she wanted to do. This book was for the people, while she later wanted to do a more scientific study. I am not sure if she was able to ever finish that, but when I search her name, this is the only book that tends to pop up. She mentions:

“I hope that, if I have misunderstood a point, my Egyptian friends will not hesitate to inform me. I am most anxious that educated Egyptians should recognize the importance of the anthropology and folklore of their country, and my earnest hope is that some of them will be persuaded to take up this study. They surely, if they received the proper training, would be best able to undertake anthropological research among their own people. Before very long I much hope that I may see a flourishing anthropological institute established in Cairo, forming a centre for all such research work, not only in Egypt itself, but in adjacent countries—for who knows how far the influence of ancient Egypt has extended ? Some writers in England even postulate an almost world-wide diffusion of Egyptian culture !”

“[This is only the beginning… I have not yet touched Lower Egypt, and] “would like to include in my researches the whole of Egypt proper, plus the Egyptian Oases and Lower Nubia.” I really wish she could have continued. There are some great details of things we can learn from ancient Oasis and ancient paths that predated Egypt.

She took all the photographs herself, with the exception of a few from her friend.

“Finally, I should like to point out that with the spread of education the old customs and beliefs are already beginning to die out. It is thus most important that they should be recorded at once, before they suffer complete extinction. I hope, therefore, that my work may not be left unfinished for lack of financial support, and that this book may awaken sufficient interest in Egypt and in England to induce those who have the means and the power to support my researches for some years to come and to enable me to bring them to a successful conclusion.”

This breaks my heart. Already in the 1920’s, she was seeing the old customs dying out. I can only look with gratitude to people like her who shared their knowledge of the past before it was gone forever.

Sources

Her work is old enough that it is available for free in online format. Copies for purchase are in the hundred dollar range, and I am incredibly grateful for sites like this.

The Fellahin of Upper Egypt by Winifred S. Blackman

Guardians of Ancient Wisdom

Winifred work reveals that the peasant women of rural Egypt were far more than agricultural laborers—they were the keepers of millennia-old traditions. Living in relative isolation along the Nile, particularly in Upper Egypt, these communities preserved customs that "have remained almost, if not entirely, unchanged from Pharaonic times."

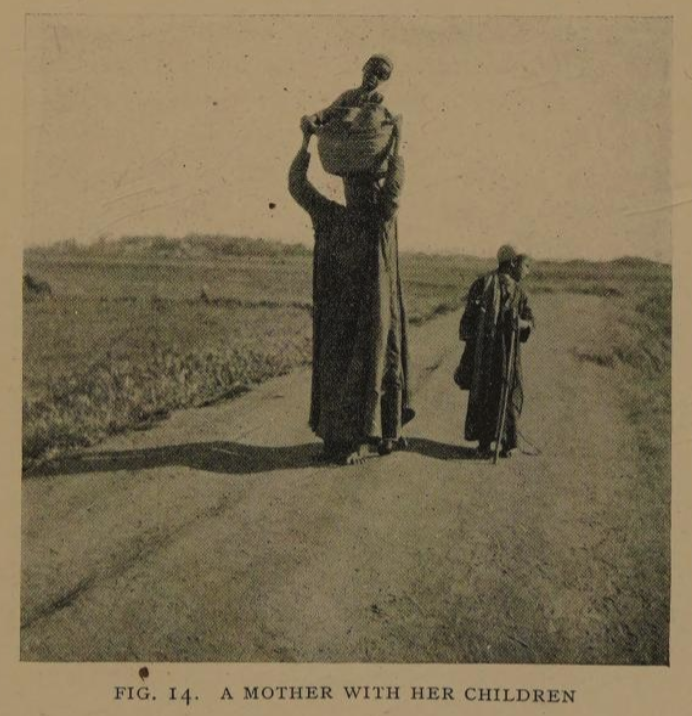

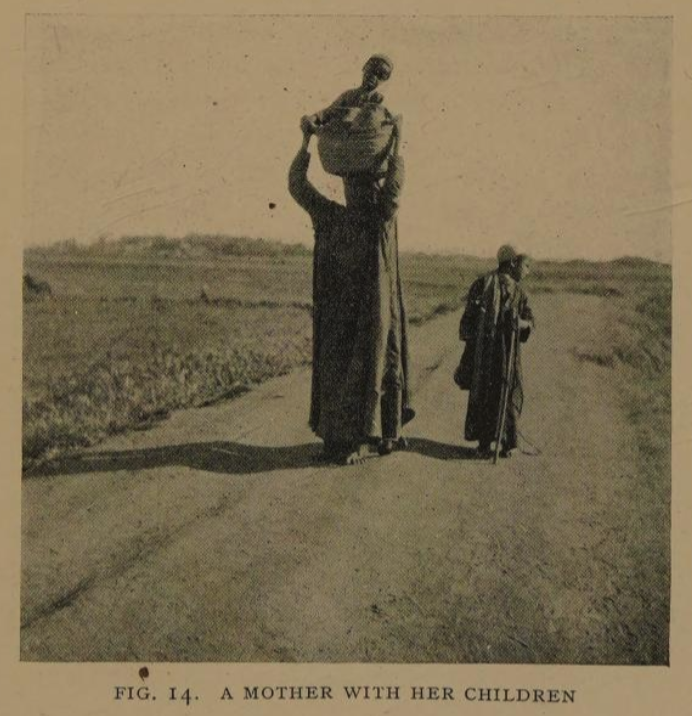

The women Bartholdi would have encountered held onto an almost mystical connection to their ancient heritage. They wore jewelry that echoed pharaonic designs, practiced tattooing patterns unchanged since the Middle Kingdom, and maintained birth and childhood rituals that could be traced directly to ancient Egyptian texts. Their long, flowing robes and veils created silhouettes that would have seemed familiar to any ancient Egyptian tomb painter.

The Sacred Feminine and Maternal Reverence

Perhaps most striking to a recently modern European observer would have been the profound reverence these communities held for mothers. As Blackman documented, "A man's love and respect for his mother is a marked characteristic among Egyptians." One villager explained to her: "My wife is good, and I am pleased with her, but she must remain there [pointing downward]. My mother is up there [pointing upward]. Did she not carry me here for nine months? Did she not endure pain to give me birth, and did she not feed me from her breast? How could I not love her? She is always first and above all with me. My wife may change and may lose her love for me. My mother is always the same ; her love for me cannot change.”

Love can come and go- but a mother’s love is possibly the most persistent thing we could ever have in our lives. And if we do not have it, a part of us will always crave it. (I know it, I lost my mom at 17, after she struggled with mental illness). A father’s love is also absolutely essential, but there is something about our mother’s hug that will always feel like home. To me, at least.

This observation by a man hist something important, it does not seem to be merely personal preference— his mentality reflects a spiritual reverence that echoed ancient Egyptian relgion, where goddesses like Isis represented the divine mother principle, associated with the earth, and essential waters of the Nile. The fellahin women embodied this sacred maternal role, serving as protectors, healers, and spiritual guides for their communities.

“In later years a woman, especially if she has sons, has an honourable position in the family. A man’s love and respect for his mother is a marked characteristic among Egyptians, and even after marriage the mother retains the highest place in her son’s love and respect. Some years ago I was told that if a man illtreated his mother and did not show her the greatest honour and respect the whole village would consider him a reprobate. In the married son’s household his mother reigns supreme, and the wife who does not show proper respect to her mother-in-law usually has | no chance of finding favour with her husband.” -Chapter 2, Winifred Blackman

More insights from Chapter 2: The Women and Children

“Foreigners are often heard talking about ‘the poor Egyptian woman.’ She is spoken of as over-worked and ill-treated, and her husband as a brute without feeling or thought for her. I would have my readers bear in mind that in this book I am dealing only with the fellahin ; I have no intention of discussing or criticizing the aspirations for emancipation which are now finding voice among many Egyptian ladies of the upper classes. What I have to say here concerns the peasants only, among whom I have sojourned for several years. No one is more anxious than I am to see the status of Egyptian women raised, for until they are made fit to hold a higher position in their world there is, I think, little chance of the country taking a more exalted place among the nations of the earth.”

“Girls are taught the best way of carrying out their domestic duties, which are, after all, very simple—how to cook their food in a cleanly way.” It is simple stuff, wash hands before cooking, wear a clean, not dirty dress when in the kitchen.

“They should also be made to realize that if they would spend but half an hour to an hour every morning sweeping their mud floors and the ground outside their house-doors, and then burning the refuse, they would have both healthier and brighter homes and villages.” This was interesting to me. We learn in many native communities a reciprocol relationship between humans and the earth. Humans carved out placed to live- not adapting to the wild only, but adapting the wild to them. Native americans burned brush annualy, and cut down many trees to make spaces for living. The rainforests of the world are considered by some experts to be someone’s ancient garden of favorite plants. And the climate loved it enough to keep it going for untold generations. We may never really know the truth to how much of the modern world was shaped by humans, but it takes effort, and skill, and simple insights like this, to SWEEP YOUR HOUSE for an hour ever single day, to keep the desert out. As we study the oasis as an ecosystem, we see how fast the desert sets in without human settlement. And the humans allow the trees to thrive, and many many animals as well. We can be great gardeners, as long as we see a limit to our reach. A heavy hand is not always the best. We have to practice and learn and listen to the world around us and our elders. The plants live on much longer than us, but we can guide a sapling’s growth so it will be a “productive” plant for our children’s children and beyond.

“Little girls have a perfectly free life until they reach marriageable age, when their freedom is somewhat more restricted. After marriage they are still more secluded, but the degree of seclusion varies, being rather stricter among the better-class peasants than among those of lower social status. Among the lower classes, there may be considerable freedom of intercourse between the sexes. It must be remembered that there are quite definite social grades among the fellahin, the lines of demarcation being very strongly emphasized. For instance, in a family well known to me the women are not allowed to speak freely to the men, and, with the exception of the elderly mother, none of the females are allowed to enter a room in which male visitors may be seated, and even the mother does not appear unless there is something which renders her presence necessary. One of the women in this family is a widow of about thirty years of age, possibly a little older, and her brother objects to her even being seen walking in the streets of their village, except when she goes, accompanied by her mother, to get the water for household use or for some other necessary purpose. He told me that if he allowed her to be seen walking about in public places his family would at once lose their position, and they would be looked down upon as nobodies.”

This was striking to me:

“To our Western ideas such restrictions are apt to be regarded as a form of tyranny, but it is not a fair judgment. Seclusion is partly a sign of respect among Egyptians, and indicates the value that the men put upon their womenfolk.”

“Though theoretically they are supposed to be entirely in subjection to the male sex, in practice they can, and often do, maintain a very firm hold on their husbands. I have known many men who are in mortal terror of their wives. Indeed, I am often inclined to think that it is the poor oppressed Egyptian man who has a claim to my sympathy, and that the over-ruled, oppressed wife is somewhat of a myth.”

“More often than not a man marries a girl from his own village, the favourite marriage being with a daughter of his father’s brother. On the smallest provocation, some imagined slight, for example, a girl will run off to her father’s or brother’s house, and remain there until her husband, from fear of mischief being made against him in the village by his wife’s relations, is induced to agree to do whatever his wife demands of him. She may require him to buy her gold earrings, a nose-ring, an anklet, or fine clothes, and, though a poor man, he may feel obliged to purchase one or more of these articles for fear of what his wife may do. Many men have run into debt for such reasons.”

To have two wives is expensive, but not prohibited. “Monogamy is becoming much more common in Egypt.”

“With regard to the division of labour among the sexes, the men certainly have the hardest and largest share. Living is simple among the peasants, so that very strenuous work for the women is not necessary.”

“It is, of course, very difficult for the peasants to be as clean as they should be. All the water has to be fetched by the women, often from some distance. No water is laid on in the villages, and no bathrooms exist. The instinct of the Egyptian fellahin, however, is to be clean, and the religion of Islam commands ablutions. A man will almost instinctively strip and bathe if he happens to be near a canal or the river, but this privilege is denied to the women, as modesty forbids their bathing in public.”

“One of the most crying needs in Egypt is that both girls and women should have instruction in the care and upbringing of children. The children undergo a great deal of unnecessary suffering during the early years of their infancy ; not because their mothers are lacking in affection, for Egyptian women are, as a ‘rule, devoted mothers, but because they are so hopelessly ignorant.”

Even he peasants will spend an enormous amount of money for spiritual amulets and written charms, but refuse to see a doctor. “Most of the women have a deeply rooted objection to going to a doctor for advice. It is encouraging to hear that the Egyptian Government has recently allocated a certain sum of money for the purpose of starting baby welfare centres. If only these institutions can be got into good working order.”

“put an end to a vast amount of unnecessary suffering. During the years I have lived among these people I have had hundreds of sick children of all ages brought to me, and it has been heartbreaking to realize, as having had no medical training I inevitably must, that I am quite incapable of dealing with the terrible diseases from which they are often suffering. As will be seen in some of the subsequent chapters, a great deal of this sickness is due to superstition—taboos against washing, for instance, being very strict.”

“Marriage is, of course, the one and only aim in life among the girls, and the desire to get a husband is encouraged in every way by the mothers. It is quite a pitiful sight to see a little girl decked out in all the jewellery she can muster, dressed in a gaily coloured frock decorated with beads and jangles (Fig. 17), and with a veil drawn coquettishly across her face, standing about the village street, or outside the house, obviously on the look-out to attract some man… There is now a law forbidding a girl to marry till she is sixteen and a boy till he is eighteen. However, in small, out-of-the-way villages the law has been disobeyed.”

“The childbearing age lasts over a long period, for girls mature early, and it is a common thing in Egypt for a woman_of fifty to give birth to a child. From an economic point of view it is probably an advantage that so many of the children die, for otherwise the country would soon become over-populated.”

Here I see influence of the more modern sentiment as influenced by a more patriarchal Greeks and Roman civilization than would have been under the Egyptians. Of course, emphasis on children was always there, but this goes to an extreme:

“If a girl has misconducted herself before marriage, and is discovered at marriage to be unchaste, the disgrace to her family is looked upon as such a terrible one that her own parents will often kill her.”

“the unfortunate child—for she is hardly more than a child…”

And here I see evidence for my theory:

“The moral standard is very much lower in some villages than others, and I have observed that villages of pure, or comparatively pure, Egyptian stock are more moral sexual, more honest, and less prone to crimes of violence than are those of mixed negro or Arab origin.”

In later years a woman, especially if she has sons, has an honourable position in the family. A man’s love and respect for his ' mother. is a marked characteristic among Egyptians, and even after marriage the mother retains the highest place in her son’s love and respect.

“I fear I may seem to have given a very unpleasant impression in many respects of the peasants of Egypt, but I have dwelt on the darker side of the picture at some length not because there is no brighter side, nor because I am lacking in appreciation of the many excellent qualities to be found in most of my village friends. It is because of my real affection for them, and because I very greatly desire to see their lives improved, especially from the moral standpoint, that I venture to speak openly on a subject in which I am much interested—z.e., how to assure a more wholesome childhood and a higher mental training for the girls, so that they may be better and wiser wives and mothers.”

“I have every cause to speak of these people with affection, for their courtesy to me has been unbounded, and I have often marvelled at their patience and cheerfulness, even in the midst of poverty and great privations, which they bear with a courage that enforces respect. Their kindness to each other in times of trouble is most marked, and they will as a rule, however poor they may be, share their scanty fare with one whose position may be even worse than their own. This nobler side of their character shows what a fine people they might become were the women, the chief influence in any community, to receive a better training in childhood, a more suitable education, and to have held up before them a higher ideal of life.”

On Jewelry

“In some parts of Egypt a girl on becoming a bride may don such a number of glass bracelets of various colours that they completely cover both arms from wrist to elbow! Silver or white metal bracelets of particular design may also now be worn by her. I was told in Asyit Province that unmarried girls are never allowed to wear this type of bracelet, which is thus a means of indicating social status.”

On Tattoos

“clients can choose whatever pattern or patterns they prefer. Some are very elaborate, and must involve considerable suffering on the part of the person who is tattooed with them. Many of the patterns are conventional designs, and I am assured that they have no special meaning, but are chosen according to individual taste and fancy. One pattern is called esh-shagerer (the tree), and is the one usually chosen by both men and women to decorate the back of the right hand. So far as I have observed, this pattern when used by women differs slightly from that used by men.”

This makes me think the meaning has been lost, though the tradition itself survives.

“The tattoo on the back of the hand and wrist, as well as on the fingers and thumb, is said to make them strong.”

On Hair

“Long hair is certainly considered a woman’s glory in Egypt, though I have rarely, if ever, seen really thick, long hair among the fellahin women and girls. However, this defect is easily remedied, and every woman buys long plaits of false hair, which hang down far below her waist. She cuts her hair short on either side of her face, and forms this short hair into flat curls against her cheeks. Over her head she ties.a silk or cotton kerchief, a brightly coloured one if she is young, a more sombre one if she has passed her YOUtH, and this keeps’ the side curls in position. The hair is not dressed every day, but when it is done a double wooden comb is used (Fig. 26), with fine and coarse teeth. The centre of the comb is usually decorated with coloured designs.”

It is interesting to note that deeper African traditions see the comb as the symbol for god. It is the base from which all things sprout. We actually see this in some hieroglyphs where a comb is representive image of a god, and many scholars wonder why.

On Birth and Childhood

“Children occupy a very important place in Egyptian society. Numerous methods employed by women to ensure their producing offspring. When a woman becomes pregnant she often hangs up in various rooms in her house pictures of legendary persons who are renowned not only for physical beauty, but also for their loving and gentle disposition. The expectant mother believes that if she constantly looks at such pictures the child to be born will resemble them in face and character. Anything and everything that she gazes at for any length of time is believed by her to affect her unborn child. This is also a common belief in England.”

“The first year that I visited Egypt I was on more than one occasion somewhat embarrassed by the numbers of women who would sit or stand around me when I happened to be visiting a village, staring at me without moving their eyes from my face. I was afterward told by my servant, who always accompanied me and assisted me greatly in my work, that these women were all expectant mothers and desired to have babies resembling me in face—hence the rigid stares! Since then I have frequently been gazed at in this manner, but have now quite lost my first feelings of embarrassment.”

‘Ah,’ said one woman when thus engaged in studying my features, ‘ if I had a girl like her I could marry her for a thousand pounds!’

‘Look well, O girl,’’ replied my servant,‘ and if you are in a state of yearning you may have one like her!’

For a similar reason most women in this condition will endeavour to avoid ugly or unpleasant sights or people, fearing that their unborn infants may be thereby adversely affected.”

“The women often have a craving to eat mud during their pregnancy.” (signs of malnutrition) “They go to the bed of a canal and break up into small pieces some of the clods of mud which have partially dried up since the inundation. They keep a store of these in their pockets or tied up in their veils, so that they may have them handy when the craving comes upon them. These pieces of mud are called tin ibliz (mud from the Nile’s flood waters). This curious craving by an expectant mother is common in some other parts of the world, as well as in Egypt.”

I have to note the “iz sound from flood waters, the is- sound”

“When a woman who is a Christian, whether Copt, Protestant, or of any other denomination, has given birth to a child her relatives take some wheat flour and mix it with water. Out of this dough they make several crosses, sticking them on the walls of the room occupied by the mother and child. The greatest number of crosses is placed in that part of the room where the child lies.”

“Childlessness is a real terror to them, and the more children they have the happier they are.”

A prayer: “O God, by thy mighty name and powerful arm, and thy Beneficent Light of Thy Face, protect the bearer of this my charm.” (The sun symbolism!)

“The naming of the child is part of the seventh-day ceremony. If the parents are anxious to discover the best and luckiest name for their offspring they proceed as follows. Candles, usually four in number, sometimes of different colours, are procured, and a different name is inscribed on each. All these candles are lighted at once, and the name on the candle which burns the longest is the one eventually bestowed on the child. After it has received a name the birth is entered in the Government archives, the name of the child’s mother only being given; the father’s name is not entered at all.”

“Women are supposed to suckle their children for two years”. In ancient Egypt, this had been four years.

“It is a common belief all-over Egypt that the souls of twins when they have passed babyhood often leave their bodies at night and enter the bodies of cats. These animals, therefore, are usually very kindly treated. It is believed that if a cat is killed while the soul of a twin is in its body the twin dies also. For this reason cats are rarely killed.”

Ancient Forgotten Places

“On the site of an ancient temple in Middle Egypt is a pool of water in which large inscribed stones are partly submerged, while others lie on the ground close by. The site is called el-Keniseh (the Church) by the peasants, probably because it became known that it is the site of an ancient temple. This pool is believed to possess miraculous powers, and every Friday childless women flock thither from all the surrounding villages. They clamber over the stones on the edge of the pool and also over those which are partly submerged, performing this somewhat arduous feat three times, and going more or less in a circular direction (Fig. 49). After this they hope to conceive.”

“Curiously enough, women come to this spot and act in the same manner to prevent conception.” They will also eat castor oil seeds for this purpose.

“On the occasion of my visit to the pool one of the women who was there told me that she had come for this latter purpose. She did not want to have another child for some time, as she had one or two very young children living Women also come here if they are experiencing difficulty in suckling their children, and donkeys which are not producing sufficient milk for their young are likewise driven here. The ceremony is the same as that for childlessness, and after its performance the milk is supposed to be much increased in quantity.”

“Many years ago my brother, Dr A. M. Blackman, recorded a custom of hanging skins of foxes over the doors of houses in Lower Nubia. On inquiry he found that they were believed to be charms “to protect the women of the household, preventing miscarriages, and helping them in labour.”’ In some parts of Egypt if a mother wants another child she will attach a small piece of fox’s skin to the head of her last-born living child. After doing this she hopes that her wish will be granted.”

On Saints

The chapter on Muslim sheikhs and Coptic saints in Blackman's work reveals one of the most fascinating examples of religious syncretism in human history—how ancient Egyptian goddess worship survived for millennia by disguising itself within new religious frameworks.

The Transformation Process: From Goddess to Saint

The Mechanism of Religious Camouflage

When Christianity and later Islam arrived in Egypt, the ancient goddess traditions didn't disappear—they underwent a sophisticated transformation. Local communities simply transferred their devotional practices from goddesses like Isis, Hathor, and Taweret to newly created "saints" who possessed remarkably similar attributes and powers.

Blackman observed that many saints were "claimed by Muslims and Copts alike," suggesting they represented spiritual forces that transcended formal religious boundaries—exactly like the ancient deities they replaced.

The Creation of Saint Mythology

Blackman documents how new saint traditions were literally invented through divine visions. The story of Sheikh Hasan 'Ali exemplifies this process: an 18-year-old boy dies and later appears to his father in a vision, demanding a tomb be built and providing written instructions for its construction, including the location of a previously unknown well.

This pattern—divine appearances demanding tomb construction—mirrors ancient Egyptian practices where deceased pharaohs and priests were deified through similar revelatory experiences. The "paper with written instructions" that conveniently disappears after the tomb's completion suggests these visions served to legitimize the transformation of local sacred sites.

Ancient Festivals and the Birth of Celebration

The fellah communities preserved fascinating birthday traditions that may represent the very origins of such celebrations. Children received elaborate seventh-day naming ceremonies involving candles, special waters, and community gatherings. These rituals explicitly connected the child to solar symbolism—as Blackman noted, "when a child is born it is said that a new star appears in the sky."

The use of candles in these celebrations deserves particular attention. Ancient Egyptians venerated Re, the sun god, as both king and queen of the heavens—a divine principle that transcended gender while embodying both solar power and nurturing light. The fellahin birthday customs, with their emphasis on candles and stellar connections, preserved this ancient understanding of light as divine presence and protection.

Annual festivals in these communities centered around saint veneration, where "candles are a favourite form of votive offering" and were "kept burning every night in some sheikhs' tombs." These practices created a continuous tradition from ancient Egyptian temple lighting rituals through to modern birthday celebrations worldwide.

Baptism, Holy Water, and the Waters of Life

The baptismal practices Blackman observed among both Coptic Christians and Muslims in these communities reveal profound connections between spiritual rebirth and maternal creation. The Copts practiced total immersion baptism in water contained in ground-level tanks, while elaborate purification rituals surrounded Muslim births involving specially blessed water called "water of the angels."

These customs illuminate the deeper symbolism of baptism as spiritual rebirth through sacred waters—a concept that mirrors the life-giving amniotic waters of the womb. Ancient Egyptian religious texts spoke of rebirth through the waters of Nun, the primordial ocean, and these fellah communities maintained rituals that preserved this understanding of water as the medium of both physical and spiritual birth.

The parallel becomes even more striking when we consider that ancient Egyptian creation myths began with the primordial waters giving birth to the sun god Re, just as human life begins in the waters of the womb before emerging into the light of day.

Hidden Goddesses: Saints as Spiritual Camouflage

Blackman's work (actually a white woman, but regardless… ;) reveals how Christian and Muslim saint veneration in these communities often masked far older traditions. Female saints like "Sheikheh Sulth" and "Mari Mina el-'Agayebi" received devotion that clearly echoed ancient goddess worship. Women brought offerings to these saints for fertility, protection in childbirth, and healing—precisely the domains of ancient Egyptian goddesses like Hathor, Isis, and Taweret.

The practice of hanging votive offerings in saint shrines, including "bunches of human hair" and "first-fruits of the cornfields," mirrors ancient Egyptian temple practices. Most tellingly, many of these saints were claimed by both Muslims and Christians, suggesting they represented spiritual forces that transcended formal religious boundaries—much like the ancient deities they likely concealed.

The Reputation for Motherhood

In their reverence for mothers, their celebrations of life's passages, their understanding of water and light as sacred forces, and their ability to maintain spiritual connections across religious boundaries, these women demonstrated that the deepest human insights transcend any single culture or creed. Perhaps this is what Bartholdi truly saw—not just an Egyptian peasant woman, but a universal symbol of the feminine principle that nurtures, protects, and illuminates the world.

The Tragic Fragmentation: When Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Confusion

Yet by the time Blackman conducted her research in the 1920s, she was documenting the twilight of this extraordinary cultural preservation. What emerged in the following decades was perhaps even more heartbreaking than complete loss—a confused mixture where women retained fragments of ancient practices without understanding their original purpose, while simultaneously rejecting traditional wisdom that had protected children for millennia.

Modern Egyptian women often find themselves caught in a devastating middle ground. They may instinctively practice diluted versions of ancient rituals—lighting candles for celebrations, seeking blessings for their children, maintaining certain birth customs—yet they're often isolated from both the deep wisdom these practices once carried AND the benefits of truly modern medical knowledge.

Blackman witnessed this tragic confusion firsthand. She described mothers using "various primitive medicinal remedies" that were "of such a nature that one wonders how any child manages to survive at all," while simultaneously having "a deeply rooted objection to going to a doctor for advice." The problem wasn't that ancient practices were inherently harmful—many contained profound wisdom about child-rearing, nutrition, and healing. Rather, successive waves of foreign occupation and religious conversion had scrambled the transmission of knowledge, leaving women with fragments of practices whose original logic had been lost.

Perhaps most heartbreaking were the cases where women followed distorted versions of ancient protective rituals that actually harmed their children. Blackman documented infants covered in "terrible sores" because mothers feared washing them, following taboos whose original purpose had been forgotten.

“On one occasion a child was brought to me in a most filthy state, and covered from head to foot with suppurating sores. I told the mother that I would not give her any medicine until she had washed the child. On hearing this she became terribly distressed, and declared that she could not wash it. She told me that if the father or mother suffered in this way, their children were never washed at all until they were old enough to wash themselves. As for the child which was brought to me, ~I am glad to say that at last persuaded the mother to wash to a certain extent, and I gave her some medicine. This happened a few years ago, and on my visiting the same village again some time later I was glad to hear that the child was well and flourishing.”

These weren't ignorant women—they were the inheritors of sophisticated medical and spiritual traditions that had been corrupted by centuries of cultural disruption. We will never know if there was ever a grain of truth to this wisdom, but without context, it becomes extremely dangerous.

The result is a generation of mothers who suffer from what we might call "wisdom whiplash"—suspicious of both old and new knowledge because they've seen both fail. They carry genetic memories of practices that once worked, but lack the context to distinguish effective ancient wisdom from harmful superstition. Simultaneously, they've witnessed the failure of modern systems that promised better outcomes but often delivered cultural alienation instead.

The Children Caught Between Worlds

Most tragically, it's often the children who pay the price for this cultural confusion. Blackman observed that "the children undergo a great deal of unnecessary suffering during the early years of their infancy; not because their mothers are lacking in affection, for Egyptian women are, as a rule, devoted mothers, but because they are so hopelessly ignorant."

This "hopeless ignorance" wasn't stupidity—it was the natural result of cultural knowledge systems being shattered and imperfectly rebuilt. Women who might have been brilliant traditional healers and child-rearers if they'd lived in an intact cultural system instead found themselves navigating between incompatible worldviews, often choosing the worst elements of both.

The fellah mothers Blackman studied possessed remnants of birth rituals that originally ensured proper nutrition for mothers and babies, timing of weaning that optimized child health, and community support systems that protected vulnerable families. But by the 1920s, many women practiced only the ritual elements while losing the practical wisdom that made them effective.

The Universal Lesson

Today, we see similar patterns worldwide as traditional cultures encounter modernity. Women everywhere struggle to navigate between ancestral wisdom and contemporary knowledge, often feeling forced to choose between systems that each offer only partial solutions. The fellah women's experience offers both inspiration and warning: it shows us the incredible resilience of feminine wisdom across millennia, while also demonstrating how easily that wisdom can be corrupted when its transmission is disrupted.

The Living Library of Human Experience

When Bartholdi chose a fellaha as his inspiration, he was unconsciously recognizing these women as living embodiments of humanity's most enduring spiritual insights. They carried in their daily practices the accumulated wisdom of thousands of years—from the sophisticated understanding of light and water as divine forces, to the recognition of motherhood as sacred calling, to the preservation of community celebrations that honored the cycles of life.

The Statue of Liberty, with her torch held high, ultimately became a monument to these principles: the light of wisdom passed down through generations, the maternal protection offered to all who seek refuge, and the enduring strength of women who preserve what matters most even in the face of changing times.

Today, as we grapple with questions of tradition and modernity, spiritual meaning and scientific understanding, the fellahin women of Blackman's study offer us a remarkable example—and a sobering warning. They show us how ancient wisdom can be preserved not in museums or books, but in the living practices of communities who understand that some truths are too important to lose. But they also demonstrate how fragile that transmission can be, and how devastating it is when cultural knowledge becomes fragmented.

Perhaps the most important lesson from these extraordinary women is that we need not choose between ancient wisdom and modern knowledge—but we must be incredibly careful about how we integrate them. The goal should be to preserve the best of traditional practices while embracing beneficial innovations, rather than abandoning entire knowledge systems or accepting them uncritically.

In their reverence for mothers, their celebrations of life's passages, their understanding of water and light as sacred forces, and their ability to maintain spiritual connections across religious boundaries, these women demonstrated that the deepest human insights transcend any single culture or creed. Their tragedy—and our opportunity—lies in learning to honor both the torch of ancient wisdom and the light of new understanding, ensuring that future generations inherit the best of both worlds rather than the worst of neither.

Timeline: The Enduring Fellahin Women of Egypt

Ancient Foundation (3100-30 BCE)

3100 BCE - First Dynasty establishes Nile Valley agricultural communities; women hold sacred roles as priestesses and keepers of household traditions 2600-2100 BCE - Old Kingdom tomb paintings show women performing the same domestic and agricultural tasks still practiced by 1920s fellahin 1550-1070 BCE - New Kingdom religious texts establish goddess worship (Isis, Hathor, Taweret) that would later be absorbed into saint veneration 664-332 BCE - Late Period: Rural communities develop strong local traditions as urban centers face political upheaval

Foreign Occupations - The Great Survival (332 BCE-641 CE)

332 BCE - Alexander's Conquest: Greek elites rule cities; fellah women maintain village life unchanged 30 BCE - Roman Occupation: Men conscripted for armies and public works; women become primary keepers of local customs and oral traditions 284-305 CE - Diocletian's Persecution: Christian communities form in rural areas; ancient goddess rituals begin merging with early saint veneration 395-641 CE - Byzantine Rule: Official Christianity imposed; rural women adapt by transferring reverence from Isis/Hathor to Virgin Mary and female saints

Key Pattern: Each occupation targets men through military service, taxation, and forced labor, leaving women as the stable core maintaining community continuity

Islamic Integration and Saint Synthesis (641-1517 CE)

641 CE - Arab Conquest: Islam arrives; fellah women seamlessly transfer ancient practices to new framework 700-900 CE - Golden Age of Saint Creation: Ancient goddess sites become tombs of invented Muslim saints; Coptic communities develop parallel Christian saint traditions 969-1171 CE - Fatimid Period: Sufi mysticism allows ancient Egyptian magical practices to continue under Islamic terminology 1250-1517 CE - Mamluk Era: Rural isolation increases; women's traditions crystallize into forms that would persist into modern times

Ottoman Stagnation and Preservation (1517-1798)

1517-1798 - Ottoman Rule: Administrative neglect of rural areas allows ancient practices to fossilize unchanged

Women's tattooing patterns remain identical to Middle Kingdom examples

Birth rituals preserve exact ancient Egyptian ceremonies

Saint veneration maintains goddess worship in disguise

Modern Encounters and Documentation (1798-1927)

1798 - Napoleon's Expedition: First European documentation of fellah customs; scholars note "remarkable conservatism" 1805-1848 - Muhammad Ali's Modernization: Urban Egypt transforms; rural women's communities remain untouched islands of antiquity 1869 - Suez Canal Opens: Bartholdi encounters fellah women, sees them as embodying eternal feminine principles 1886 - Statue of Liberty Dedicated: Bartholdi's vision of the torch-bearing woman ultimately derived from these ancient-modern figures 1920-1927 - Blackman's Fieldwork: Documents traditions on verge of disappearing due to education and modernization

The Strange Inheritance - Modern Fragmentation (1927-Present)

1920s-1950s - Educational Disruption: Government schools begin breaking transmission of oral traditions; ancient knowledge becomes fragmented 1952-1970s - Nasser Era: Rural development projects displace traditional communities; women lose connection to ancient sites and practices 1970s-2000s - Urbanization Wave: Rural women migrate to cities carrying diluted memories of ancient customs Present Day - Isolated Fragments: Modern Egyptian women unknowingly practice ancient rituals (henna ceremonies, evil eye protection, reverence for motherhood) without understanding their pharaonic origins

The Contemporary Paradox

Today's Egyptian women exist in a peculiar state of disconnection - they may practice watered-down versions of ancient birthday celebrations with candles, seek blessings from saints who are really disguised goddesses, and maintain maternal reverence systems, yet they're often cut off from both the ancient wisdom these practices once carried AND the pure traditions their recent ancestors preserved. They're simultaneously the inheritors of humanity's oldest spiritual traditions and strangers to their own heritage - carrying the genetic memory of the fellahin but living in a world that has forgotten what the practices actually meant.

The irony: A modern Egyptian woman lighting birthday candles may be performing a ritual older than Christianity or Islam, honoring the sun god Re through practices her fellaha great-grandmother understood completely, yet she herself sees only a secular celebration borrowed from the West.