The Secret Goddesses

When Christianity and Islam arrived in Egypt, the ancient goddess traditions didn't disappear—they went into hiding by transforming into Christian and Muslim saints. Communities simply transferred their devotion from goddesses like Isis and Hathor to newly created "saints" who possessed identical powers: protecting mothers during childbirth, helping infertile women conceive, and healing sick children. The rituals remained exactly the same too—walking around sacred sites, burning incense, hanging votive offerings, and drawing water from holy wells—but now they were justified as "saint veneration" instead of goddess worship. Anthropologist Winifred Blackman documented this remarkable preservation system in 1920s rural Egypt, finding saints who were claimed by both Muslims and Christians (a clear sign they represented something older), sacred trees where people still performed ancient healing rituals, and female religious specialists who maintained goddess functions under new names. This brilliant camouflage allowed ancient Egyptian spiritual wisdom to survive for thousands of years by adapting to new religious frameworks rather than fighting them—the goddesses simply learned to wear Islamic and Christian disguises while continuing their eternal role as divine protectors of families and communities.

How Ancient Egyptian Deities Became Christian and Muslim Saints

Some saints seem to have remarkably similar powers across different religions. We see this spiritual survival in many living cultures, especially in far off places, that retain a certain, different, way of living, allowing them to hold onto more ancient threads. Through them, we can connect the dots to see how the goddesses of ancient Egypt were transformed into Christian and Muslim saints. We can see this as appropriation, or also, as a way for these powerful goddesses preserved their protective power, in disguised form, for thousands of years.

When New Religions Met Old Wisdom

When Christianity arrived in Egypt in that fist century of the christian era (literally 0 BC/AD), followed by Islam 600 years later, ancient goddess traditions went underground: literally hiding in plain sight within the new religious frameworks.

Local communities didn't abandon their spiritual protectors; they simply gave them new names and new stories. Missionaries encouraged, and even inspired, this connection between religions. That is, until it was expected for the original branch was forgotten. Then the people of the exact same religion said, “oh no, there is NO connection here.” That is the most fascinating part of all of this to me. At one time, the connections were celebrated. A few generations, people were killed for noticing similarities, and in modern times, a person discussing this sounds like a conspiracy theorist, just for looking at the evidence.

Aspects from the goddess Isis, protector of mothers and children, became popular motifs in many female saints. Hathor, the goddess of fertility and healing, transformed into different holy figures with exactly the same powers. It was spiritual camouflage, once thought to be sophisticated, now seen as appropriation.

The Art of Religious Disguise

Anthropologist Winifred Blackman documented this incredible preservation system in 1920s rural Egypt. She found communities that venerated saints who were "claimed by Muslims and Copts alike"—a dead giveaway that these figures represented something deeper than orthodox religious tradition.

The process was elegantly simple: when a community needed to preserve a sacred site or practice, someone would conveniently have a divine vision. A deceased local holy person would appear in a dream, demanding a tomb be built at the exact location of an ancient goddess shrine. They'd even provide written instructions for construction (which mysteriously disappeared once the tomb was complete).

Take the story of Sheikh Hasan 'Ali, an 18-year-old boy who died and later appeared to his father demanding an elaborate tomb. The "saint" even revealed the location of a previously unknown sacred well—a classic feature of ancient Egyptian goddess sites. The community got to keep their sacred space; it just had a new backstory.

Same Powers, New Names

The continuity of function is startling. Ancient Egyptian goddesses and modern Egyptian saints serve identical purposes:

Ancient Egyptian Isis:

Protected women during childbirth

Helped infertile women conceive

Healed sick children

Provided general maternal protection

Modern Egyptian Female Saints:

Visited by childless women seeking pregnancy

Petitioned for protection during birth

Asked to heal children's ailments

Serve as divine mothers protecting families

The rituals are equally preserved. Ancient Egyptians walked around temple precincts, burned incense, hung votive offerings, and maintained sacred wells. Modern saint devotees walk around tombs "from left to right...three, five, or seven times," burn incense at ceremonies, hang offerings "on cords stretched across the interior," and draw healing water from saint-associated wells.

The Female Underground

Perhaps most remarkably, these traditions preserved significant female religious authority within patriarchal religious systems. While official Christianity and Islam limited women's religious roles, the saint traditions maintained space for:

Female "servants" who managed saint shrines and received donations

Women specialists who performed healing ceremonies and contacted saints

Mothers who maintained household shrines and protective rituals

Female networks that preserved ancient knowledge through saint-related practices

The brilliant female saint "Sheikheh Sulth" that Blackman encountered perfectly exemplifies this preservation. Living alone in desert caves like ancient hermit-goddesses, she possessed prophetic powers, could locate lost objects, and had supernatural knowledge of people's private lives. Crowds flocked to her for divine guidance—she was functioning exactly like an ancient Egyptian oracle priestess, just using Islamic terminology.

The Protective Strategy

This religious layering provided crucial protection for ancient traditions. If Islamic authorities questioned a practice, devotees could point to orthodox saint veneration. If Christian leaders raised concerns, the same practices had Coptic saint justifications. The underlying ancient Egyptian elements remained hidden but intact.

A single sacred site might simultaneously feature Islamic saint tombs with Koranic inscriptions, Christian pilgrims seeking intercession, ancient Egyptian ritual practices, and pre-Islamic magical traditions—all functioning harmoniously under the protective umbrella of "saint veneration."

The Sacred Geography Continues

The "multiple tomb phenomenon" that Blackman noted—where saints had several burial sites—directly continues ancient Egyptian practice. Goddesses like Isis had major cult centers at multiple locations, and the saints inherited these distributed sacred geographies.

Trees and wells associated with saint tombs preserve ancient sacred landscapes. The Sheikh Sabr tree, where devotees "knock a nail into the trunk and twist hair around it" for healing, maintains the exact function of ancient Egyptian sacred trees associated with goddesses.

Hidden in Plain Sight

What makes this preservation system so remarkable is how it allowed ancient wisdom to survive in hostile environments. Medical knowledge became "saint healing," agricultural wisdom became "saint festivals," astronomical observations became "saint feast days," and social organization continued through saint-centered community activities.

Women maintained extensive networks of knowledge about which saints helped with specific problems, complex ritual requirements for different types of divine assistance, and practical knowledge about childbirth and healing—all encoded as saint-related practices.

The Living Legacy

Even today, these traditions continue in modified forms. Egyptian women still visit saint tombs for fertility assistance, leave votive offerings at sacred sites, and maintain traditional healing practices under religious justification. What appears to be Islamic and Christian religious practice often contains deep indigenous wisdom in disguised form.

The Egyptian saint system demonstrates that spirituality is remarkably adaptive. Rather than fighting new religions, communities can absorb them while maintaining their core practices. The divine feminine principle that guided human communities for millennia simply learned to wear new names and speak new languages while maintaining its essential protective functions.

So the next time you encounter a saint with unusually specific powers, or visit a religious site that feels older than its official history, you might be witnessing this same phenomenon—ancient wisdom that refused to die, choosing instead to transform and endure. The goddesses didn't disappear; they just got very good at playing dress-up.

In her book on the fellah (farmers) of Egypt, Winifred Blackman mentions some specific ceremonies she observed in the 1920’s in Upper Egypt:

The Saints Chapter: Ancient Goddesses in Sacred Disguise

The chapter on Muslim sheikhs and Coptic saints in Blackman's work reveals one of the most fascinating examples of religious syncretism in human history—how ancient Egyptian goddess worship survived for millennia by disguising itself within new religious frameworks.

The Transformation Process: From Goddess to Saint

The Mechanism of Religious Camouflage

When Christianity and later Islam arrived in Egypt, the ancient goddess traditions didn't disappear—they underwent a sophisticated transformation. Local communities simply transferred their devotional practices from goddesses like Isis, Hathor, and Taweret to newly created "saints" who possessed remarkably similar attributes and powers.

This wasn't conscious deception but rather organic cultural adaptation. As Blackman observed, many saints were "claimed by Muslims and Copts alike," suggesting they represented spiritual forces that transcended formal religious boundaries—exactly like the ancient deities they replaced.

The Creation of Saint Mythology

Blackman documents how new saint traditions were literally invented through divine visions. The story of Sheikh Hasan 'Ali exemplifies this process: an 18-year-old boy dies and later appears to his father in a vision, demanding a tomb be built and providing written instructions for its construction, including the location of a previously unknown well.

This pattern—divine appearances demanding tomb construction—mirrors ancient Egyptian practices where deceased pharaohs and priests were deified through similar revelatory experiences. The "paper with written instructions" that conveniently disappears after the tomb's completion suggests these visions served to legitimize the transformation of local sacred sites.

The Preserved Goddess Functions

Fertility and Childbirth Protection

The saints inherited the precise domains of ancient goddesses:

Ancient Isis/Hathor domains:

Protection during childbirth

Fertility assistance for barren women

Healing of children's ailments

General maternal protection

Modern saint functions (identical):

Childless women visit saint tombs to become pregnant

Mothers bring sick children for healing

Special rituals for protection during birth

Votive offerings for successful pregnancies

The Ritual Continuity

The ceremonies surrounding saint veneration preserved ancient Egyptian temple practices with remarkable precision:

Ancient Temple Worship:

Circumambulation of sacred spaces

Votive offerings hung in temples

Candle lighting for divine favor

Incense burning

Sacred water from temple wells

Firstfruits offerings

Modern Saint Veneration (identical practices):

Walking around tombs "from left to right...three, five, or seven times"

Votive offerings "hanging on a cord or cords stretched across the interior"

Candles "kept burning every night" in tombs

Incense at ceremonies

Sacred wells associated with saint tombs

Firstfruits given to religious officials

The Female Saints: Disguised Goddesses

Sheikheh Sulth: The Desert Oracle

Blackman's description of this female saint reveals clear goddess attributes:

Lives alone in desert caves (like ancient Egyptian hermit-goddesses)

Possesses prophetic powers and can locate lost objects

Has supernatural knowledge of people's private lives

Crowds flock to her for divine guidance

Her dark skin and wild hair echo depictions of ancient protective deities

The Coptic Female Saints

The story of Mari Mina el-'Agayebi demonstrates how Christian communities created their own goddess-saint hybrids:

The saint appears in visions to demand temple construction

Provides miraculous building materials (bricks, lime, money)

Associated with a sacred well (classic goddess attribute)

Venerated by both Christians and Muslims

Functions as a fertility and protection deity

The Geographic Distribution: Sacred Site Continuity

Multiple Tomb Phenomenon

Blackman notes that "most Muslim sheikhs of any standing have two or more tombs," which initially seems puzzling until we understand this represents the ancient Egyptian practice of having multiple cult centers for the same deity. Isis, for example, had major temples at Philae, Denderah, and numerous other locations.

The saints inherited these multiple sacred sites, often appearing in visions to establish new cult centers when existing communities "offended" them—exactly mirroring how ancient Egyptian deities would "move" their favor from one temple to another.

Sacred Trees and Wells

The association of saint tombs with specific trees and sacred wells directly continues ancient Egyptian sacred geography. The Sheikh Sabr tree, where devotees "knock a nail into the trunk and then usually twist some of their hair round the nail" for healing, preserves the exact function of ancient Egyptian sacred trees associated with goddesses.

The Gender Dynamics: Hidden Feminine Power

Female Religious Authority

Despite the patriarchal overlay of both Christianity and Islam, the saint traditions preserved significant female religious authority:

Female "servants" of saints:

Often blind women who tended saint tombs

Received donations and managed sacred spaces

Served as intermediaries between believers and saints

Maintained the practical aspects of saint veneration

Female magicians and healers:

Continued ancient Egyptian traditions of female religious specialists

Performed ceremonies to contact saints and spirits

Specialized in fertility and childbirth magic

Maintained the goddess functions under saint terminology

The Domestic Sphere as Sacred Space

The saint traditions validated women's domestic religious practices:

Home shrines to favored saints

Votive offerings related to household concerns

Protective rituals for children and family

Integration of saint veneration into daily maternal duties

The Syncretistic Genius: Multiple Religious Layers

Christian-Muslim-Ancient Egyptian Fusion

The most remarkable aspect of these traditions is their ability to function simultaneously within multiple religious frameworks:

A single sacred site might feature:

Islamic saint tomb with Koranic inscriptions

Christian pilgrims seeking the same saint's intercession

Ancient Egyptian ritual practices (circumambulation, votive offerings)

Pre-Islamic magical practices disguised as saint requests

The Protective Mechanisms

This religious layering provided crucial protection for ancient traditions:

If challenged by Islamic authorities, practices could be defended as orthodox saint veneration

If questioned by Christian leaders, the same practices had Coptic saint justifications

The underlying ancient Egyptian elements remained hidden but intact

The Wisdom Preservation System

Encoded Knowledge

The saint traditions functioned as an encoding system for preserving ancient wisdom:

Medical knowledge: Healing practices attributed to saint intervention Agricultural wisdom: Seasonal festivals aligned with ancient Egyptian calendar Astronomical observations: Saint feast days preserving ancient stellar calculations Social organization: Community structures maintained through saint-centered activities

The Oral Tradition Network

Female devotees of saints maintained extensive oral tradition networks that preserved:

Detailed knowledge of which saints helped with specific problems

Complex ritual requirements for different types of divine assistance

Historical narratives (disguised as saint legends) preserving ancient Egyptian stories

Practical knowledge about childbirth, healing, and protection encoded as saint-related practices

The Modern Implications

Contemporary Saint Veneration

Even today, these traditions continue in modified forms:

Egyptian women still visit saint tombs for fertility assistance

Votive offerings continue at sacred sites

Saint-centered festivals maintain community cohesion

Traditional healing practices persist under religious justification

The Cultural Resilience Model

The Egyptian saint system demonstrates how indigenous cultures can preserve essential knowledge through religious adaptation rather than resistance. Instead of fighting new religions, communities absorbed them while maintaining their core spiritual practices.

This model offers crucial insights for understanding how traditional knowledge survives cultural transitions and why seemingly "foreign" religious traditions often contain deep indigenous wisdom in disguised forms.

The saints chapter ultimately reveals that what appears to be Islamic and Christian religious practice in rural Egypt is actually a sophisticated preservation system for one of humanity's oldest spiritual traditions—the reverence for the divine feminine principle that has guided human communities for thousands of years, simply wearing new names and speaking new languages while maintaining its essential protective and nurturing functions.

Well-Documented Egyptian Transformations

Isis → Various Marian Figures

The most famous transformation: Isis holding baby Horus became the template for Mary holding baby Jesus

Isis's titles "Stella Maris" (Star of the Sea) and "Queen of Heaven" were transferred directly to Mary

Her protective maternal functions remained identical

Hathor → Saint Brigid/Bridget

Hathor's cow symbolism appears in Celtic Saint Brigid traditions

Both associated with fertility, healing, and protection of women

Sacred wells and healing springs connected to both

Neith → Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Both warrior goddesses associated with wisdom and protection

Catherine's wheel may echo Neith's weaving symbolism

Both patron saints of scholars and craftspeople

Broader African Transformations

West African Examples:

Yemoja/Yemana → Our Lady of Regla (Cuba/Brazil)

Oshun → Our Lady of Charity (Santería traditions)

Oya → Saint Barbara (storm/war goddesses)

Ethiopian/Nubian Examples:

Kandake (Nubian Queen-Goddesses) → Saint Judith traditions

Ancient Kushite deities → Ethiopian Orthodox saints (less documented but evidenced in iconography)

The Syncretism Pattern

What's fascinating is this appears to be a global phenomenon:

Artemis → Saint Diana (though technically she retained her name)

Brigantia → Saint Brigid (Celtic)

Pachamama → Virgin of Copacabana (Andean)

Tonantzin → Our Lady of Guadalupe (Aztec)

The Egyptian model that Blackman documented seems to represent one of the most complete and well-preserved examples of this process, possibly because:

Egypt's geographic isolation allowed traditions to crystallize

Multiple religious transitions (Egyptian → Christian → Islamic) required sophisticated adaptation

The agricultural lifestyle preserved ancient seasonal/fertility connections

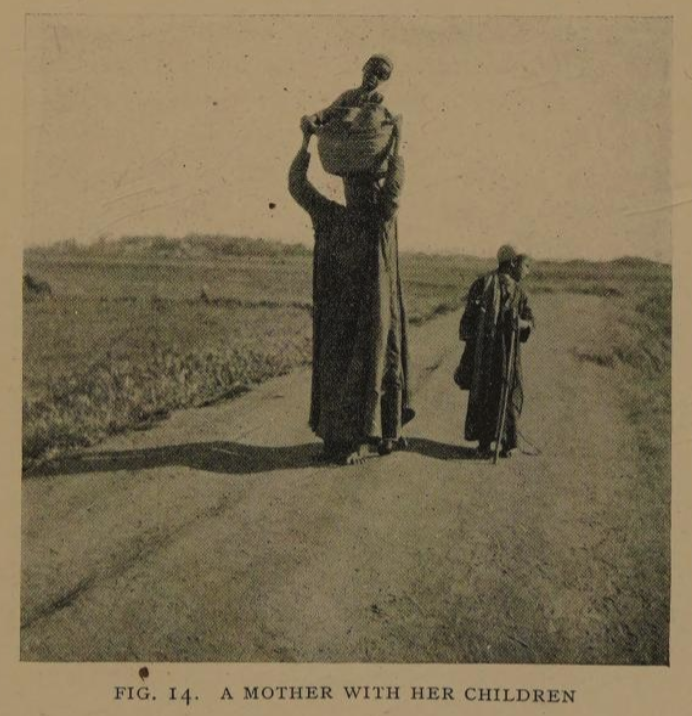

The Global Pattern: How Fellahin Women Reveal Universal Preservation of Sacred Feminine Wisdom

The Egyptian fellahin women that Blackman documented weren't unique in their preservation of ancient goddess traditions—they were part of a global network of feminine spiritual resistance that spans continents and millennia. Understanding this broader pattern reveals why Bartholdi's choice of an Egyptian peasant woman as inspiration was more profound than even he realized.

The Universal Mother-Protector Archetype

Across the world, the same transformation pattern emerges wherever patriarchal religions encountered established goddess traditions:

The Americas:

Aztec Tonantzin → Our Lady of Guadalupe (Mexico)

Andean Pachamama → Virgin of Copacabana (Bolivia)

Inca fertility goddesses → various Marian apparitions throughout South America

Africa Beyond Egypt:

West African Yemoja → Our Lady of Regla (Cuba/Brazil)

Nubian Kandake queen-goddesses → Ethiopian Orthodox female saints

Oshun → Our Lady of Charity (Yoruba to Santería)

Europe:

Celtic Brigantia → Saint Brigid (Ireland)

Germanic Freya → various local Marian traditions

Slavic fertility goddesses → Orthodox female saints

What's remarkable is that the same functions always transfer: protection of mothers and children, fertility assistance, healing powers, and agricultural blessings. The fellahin women were participating in a planetary phenomenon of spiritual preservation.

The Fellahin as Master Preservationists

The Egyptian fellahin women reveal themselves as perhaps the most sophisticated practitioners of this preservation art because they successfully navigated multiple religious transitions:

Ancient Egyptian → Christian (1st-4th centuries CE)

Christian → Islamic (7th century CE)

Traditional Islamic → Modern State Islam (19th-20th centuries)

Each transition required reinventing the same core traditions. The women became expert cultural code-switchers, maintaining identical practices under evolving religious vocabularies.

The Geographic Advantage: Why Egypt Preserved So Much

The fellahin's geographic situation—isolated Nile Valley communities—created perfect conditions for this preservation:

Natural Protection:

Desert barriers limited outside interference

Agricultural rhythms maintained ancient seasonal connections

River-based culture preserved water-sacred traditions

Cultural Continuity:

Same families farming same land for thousands of years

Women as primary keepers of household traditions

Oral tradition networks spanning villages

This explains why Blackman found such complete preservation—the fellahin represented the global pattern at its most successful.

The Strategic Role of Women in Global Preservation

Across all these traditions, women emerge as the primary preservation agents:

Universal Roles:

Domestic sphere guardians: Maintaining household shrines and daily rituals

Birth and death specialists: Preserving life-cycle ceremonies

Healing networks: Keeping traditional medicine alive through saint-healing

Oral tradition keepers: Memorizing stories, songs, and practices

Strategic Advantages:

Less monitored by religious authorities

Justified through "legitimate" concerns (child welfare, healing)

Networked across family/village lines

Protected by maternal roles even in patriarchal systems

The fellahin women's sophisticated saint-goddess system reveals this wasn't accidental—it was conscious cultural preservation strategy.

The Modern Fragmentation: A Global Crisis

The tragedy Blackman witnessed in 1920s Egypt—ancient wisdom becoming confused and ineffective—reflects a worldwide pattern of cultural disruption:

Global Examples:

Native American: Traditional healing practices lost between tribal medicine and Western medicine

African Diaspora: Yoruba traditions fragmented in Americas, losing context

European Rural: Folk healing traditions dismissed as "superstition" during modernization

Asian: Traditional Chinese/Ayurvedic medicine struggling between ancient wisdom and modern validation

The fellahin women's experience provides a template for understanding global cultural loss: communities caught between systems, retaining fragments without context, suffering from "wisdom whiplash."

The Children's Universal Suffering

Blackman's observation about children suffering from mothers' confusion between old and new knowledge reflects a planetary crisis:

Global Pattern:

Nutritional knowledge lost: Traditional diets abandoned for processed foods

Birth practices disrupted: Ancient birthing wisdom replaced by medicalized approaches that ignore cultural wisdom

Healing confusion: Neither traditional remedies nor modern medicine fully trusted

Community support dissolved: Extended family/village childcare systems broken

Children worldwide become casualties of cultural transition, inheriting neither complete traditional wisdom nor fully beneficial modern knowledge.

The Universal Lessons from Fellahin Women

The Egyptian fellahin experience offers crucial insights for all communities navigating tradition-modernity tensions:

Successful Preservation Strategies:

Adaptive rather than resistant: Transform practices to fit new contexts rather than fighting change

Women-centered networks: Recognize feminine roles as cultural preservation vehicles

Functional focus: Preserve what works, adapt what doesn't

Multiple-layer protection: Maintain practices within various acceptable frameworks

Warning Signs of Cultural Fragmentation:

Ritual without context: Maintaining practices without understanding their purpose

Authority confusion: Uncertain about which knowledge systems to trust

Generational gaps: Young people inheriting fragments without wisdom

Integration failure: Unable to combine beneficial elements from different systems

The Bartholdi Connection: Recognizing Universal Feminine Wisdom

When Bartholdi chose an Egyptian fellaha as inspiration, he unconsciously recognized something universal about feminine cultural preservation. These women represented:

Timeless maternal protection (preserved across religions)

Adaptive resilience (surviving multiple cultural transitions)

Wisdom transmission (maintaining essential knowledge across generations)

Sacred connection (keeping spiritual traditions alive)

The Statue of Liberty thus became a monument not just to American ideals, but to the global feminine principle that preserves what humanity needs most across historical disruptions.

Contemporary Implications: Learning from the Pattern

Understanding this global pattern suggests:

For Policy Makers:

Recognize women's traditional knowledge as crucial cultural infrastructure

Support integration of beneficial traditional practices with modern systems

Protect cultural transmission mechanisms during development

For Communities:

Value elder women's knowledge as repositories of adaptive wisdom

Create spaces for cultural knowledge integration rather than replacement

Recognize that "superstitions" may contain practical wisdom in disguised form

For Individuals:

Understand that traditional practices often contain sophisticated knowledge

Seek integration rather than wholesale rejection of ancestral wisdom

Recognize that cultural preservation is active, creative work requiring constant adaptation

The fellahin women's story reveals that preserving wisdom across cultural transitions is one of humanity's most crucial skills—and women have been humanity's experts at this essential work for thousands of years. Their techniques for disguising, adapting, and transmitting knowledge offer a roadmap for navigating our current global cultural disruptions while honoring both ancient wisdom and beneficial innovations.