Tylenol May Be Bad For Us?

Something's been in the news recently about the acknowledged potential harm of Tylenol on children and pregnant women.

I did a major deep dive when I was pregnant, and I feel the need to share what I found. When it comes to our children, NOTHING is off the table for discussion. Let's talk. When we should be taking extra care of our most vulnerable, we're cursing those asking for more rigorous safety measures.

Here's what we know:

Tylenol depletes glutathione, which is our body's master detoxifier. When we compromise detox pathways, toxins are able to stay in the body longer. Tylenol is often taken alongside newborn combo vaccines that exceed ADULT limits of aluminum. (The safety limit for babies is literally zero, so there is no upper limit guiding vaccine combo doses).

Safety studies have NOT been completed with combos or with Tylenol, as they happen in realty. They have only been studied for safety individually.

So we should use caution- it is not as safe to use for babies and pregnant women as first believed. We have more (newer) science that says Tylenol burdens our glutathione that is needed to remove the toxins we added.

I am not saying tylenol (or vaccines) cause autism, but that known toxins cause toxic effects when dosages are exceeded. It’s subtle. There are cumulative effects of uncharted new ingredients that have added up and show harm over the most recent generations. But there are a few simple things we can do to reduce side effects of our modern reality. These were just the few tips I pulled together by reading the fine print:

Tylenol is not as benign as we thought. So dont just take it without weighing the risks.

Don’t give your child a vaccine when they are sick (just reschedule)

Separate the combo dosages so each administration at least stays under adult problem limits (and avoids unnecessary preservatives)

If a child has known liver or kidney issues (hindered ability to remove the known toxins in vaccines), take extra precaution.

Basically, don’t overburden children's systems when we give them known neurochemicals (aka vaccines).

We're potentially compromising our children's ability to eliminate toxins at the exact moment they need that system working its best. When children can't properly detoxify aluminum and other vaccine ingredients, we see increased rates of many health issues - from respiratory problems to attention disorders to immune dysfunction. Studies link Tylenol use to increased rates of autism, ADHD, asthma, and other developmental issues. Various examples are listed in the comments.

Educating the public is important. Our babies are born today with 200+ known toxic chemicals ON AVERAGE in their umbilical cord blood. And they are not born with functioning livers to remove that burden. Then we add “pain reducers” that increase the load to remove, holding in other things longer than estimated. It’s been estimated that 1/3 of all cancers are due to known lifestyle factors. Yet less than 1% of research dollars are spent on education of those factors. This is exactly the kind of thing we need to be talking about. Removing known burdens. Tylenol is proving to be more of a burden than load bearer, at least in the long term.

This is not about use for extreme fevers- there may be moments some would say Tylenol can be really helpful- but we must weigh the risks. Acetaminophen is now the leading cause of acute liver failure in the US, and randomized studies show it's not even that effective as a pain reliever. Maybe adults using it for hangover cure are not doing themselves much of a service, in the long run, holding in alcohol toxins to dull pain. But that’s adults: who cares, when we are talking about children.

This isn't about creating fear or placing blame. It's about empowerment, and having the freedom to ask questions. It’s saying we need to be MORE cautious than we thought.

We are allowed to talk about this. Modern parenting involves calculating risk and making informed decisions. We live at an unprecedented time of freedom and access, don't let it numb you into inaction. This is diving right into the muck of an issue all political sides SHOULD find reason to unite: protecting our babies and mamas.

Closing your eyes to known studies does not mean those studies do not exist. Lack of adequate studies does NOT prove safety.

When Studies Raise Questions: A Parent's Perspective on Tylenol and Our Most Precious Humans

RFK Jr. has been making headlines recently for a couple of things—his stance on vaccines and his suggestion that Tylenol needs to be reviewed when offered to pregnant women and children. Regardless of the details of the studies, the one thing to note is everyone is saying we need more data. This is somewhere we should unite on: to make sure our most vulnerable are protected, and to err on the side of caution, whichever aisle of the political spectrum you stand on.

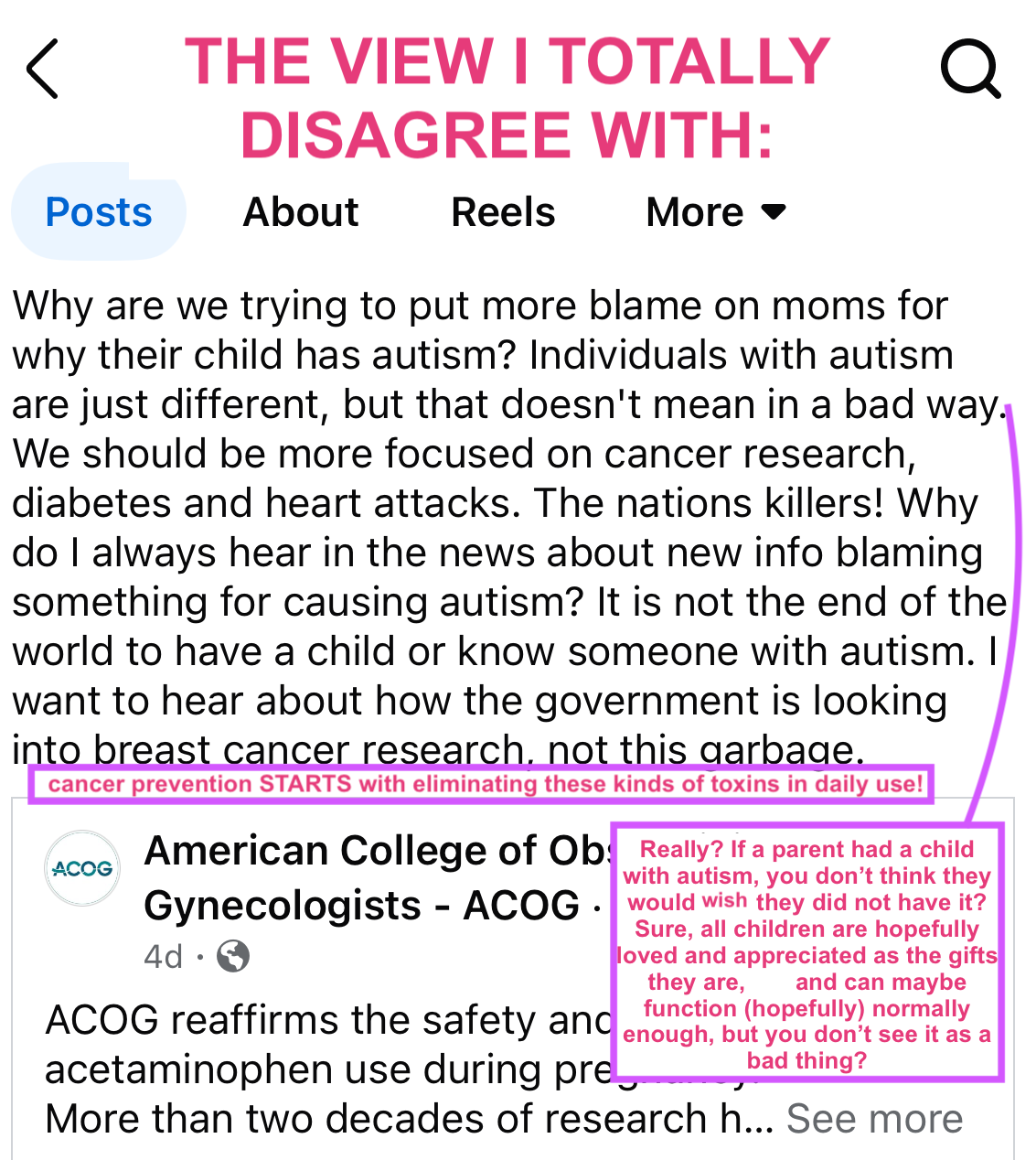

Then I saw a post today where someone was pushing back against this—a mom who happens to be a nurse, sharing how the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently reaffirmed the safety of acetaminophen (Tylenol) during pregnancy, citing "more than two decades of research showing no harm." She seemed frustrated that we keep "blaming moms" and suggested we focus on bigger health issues instead.

Here's the thing: I don't think this is about blame at all. It's about having access to information and the freedom to make informed choices for our families.

When Research Raises Red Flags

As an engineer, I understand that science is far less black and white than we like to think it is. Science is never clear-cut. In every study, there are scientists who seldom agree on every point. Usually, you'll find 50/50 opinions and conclusions going in either direction. Often, many scientists have information that runs counter to the funding source or the message that sponsors want to promote.

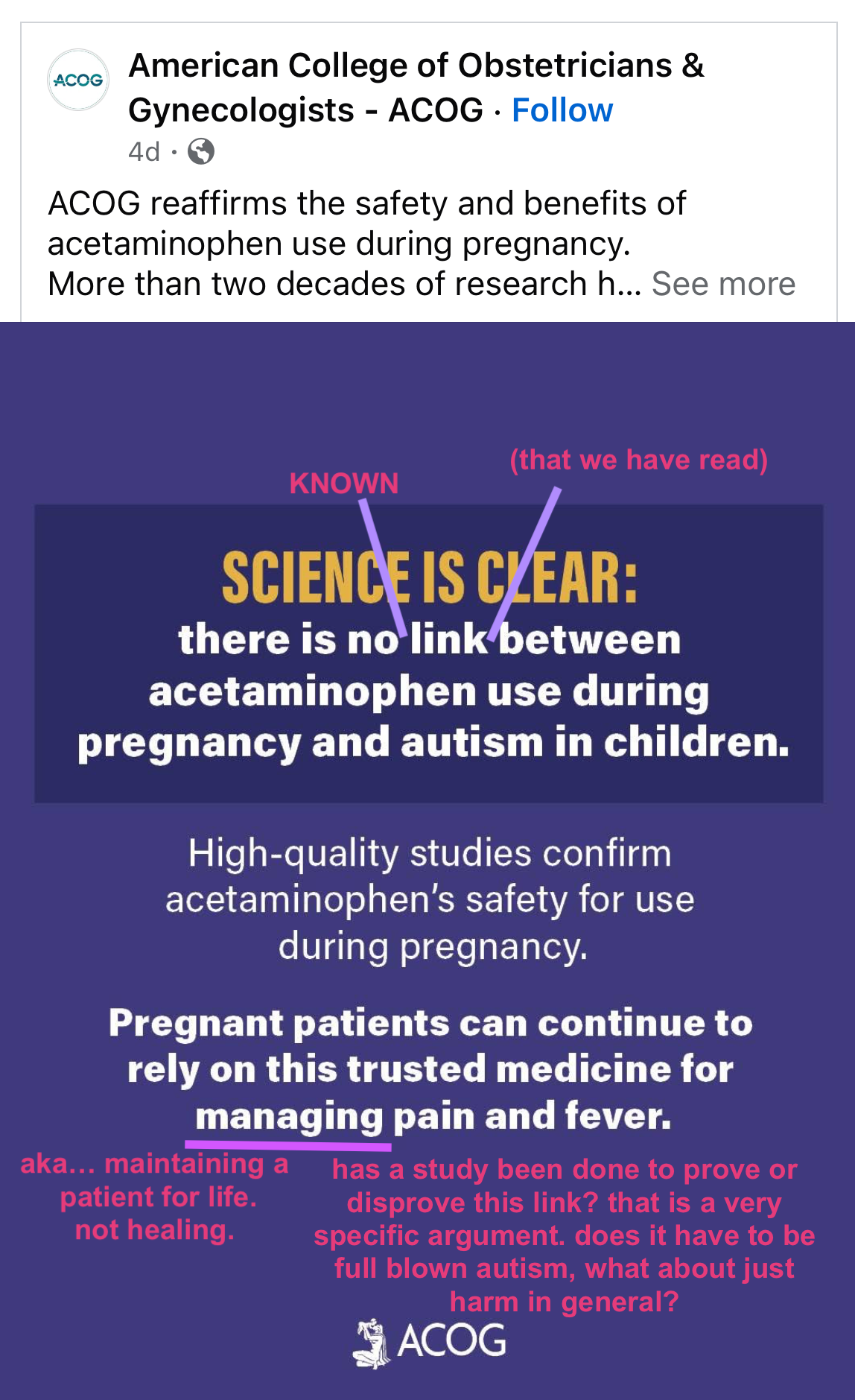

Here's something crucial that people don't always grasp: nobody can claim to prove disconnection. We can only prove links. Nobody can prove things are NOT related. For example, we might say autism was correlated with x, y, and z factors. But we can never definitively say it is NOT linked to something—only that we don't have data to say otherwise.

This is exactly what bothers me about ACOG's statement. For them to claim "There is no link between Tylenol (acetaminophen) use during pregnancy and autism in children," they are already claiming more in grammar than they have the power to. Nobody can say there is no link, only that they have not read research or data that says otherwise. Their failure to see what is in print, their lack of education, proves nothing—except that their opinion should be questioned.

Recently, some studies have raised questions about acetaminophen use during pregnancy and early childhood. These aren't fringe theories—they're legitimate research findings published in peer-reviewed journals. When any study suggests potential risks to our children, shouldn't that at least warrant a conversation?

The Power of Informed Choice

Here's something worth shouting from the rooftops: nothing is off limits for discussion as a parent. This is not about blame—it's about education. It's about learning you have the power to change things.

As humans today, we live in a world of freedom and access—unprecedented access to information, and the freedom to talk about it openly. This has never happened before in human history. We can hear from scientists themselves, read the data ourselves, not rely on the red tape political statement that comes out a decade later. It takes 17 years for information to make it into the medical curriculum. Are we willing to wait for our children to be 17 for the new nurses and doctors to be up to speed?

It's in the news that Tylenol may be harmful to kids and pregnant women. (Gasp.) So let's dive in.

As with anything, you should be able to make a hard choice. If you have a 104-degree fever, then fine—it might be worth it. But knowing that someone, anyone, any study at all says it may do harm, then don't take it daily like candy. Maybe that headache is worth suffering through for 2 hours if it could have long-term side effects on your children (assuming you're pregnant—because who cares about us as just adults, right?).

We should be equally careful with what we give our children directly.

There's so much animosity about very outdated and privately funded safety studies being questioned. LET'S QUESTION EVERYTHING. Let's talk. Our children deserve it.

The Real Science: What We're Actually Dealing With

Here's what really concerns me about how Tylenol works: it puts a heavy load on our body's main detoxification system, specifically something called glutathione. Glutathione is like our master antioxidant—its job is to grab onto waste products and toxins and help flush them out. When your body processes acetaminophen, it can use up your glutathione reserves temporarily. If that main detox pathway is busy or depleted because of Tylenol, other toxins that your body would normally clear out might hang around longer.

This became personal for me when I was dealing with adult acne. Glutathione support and morning lemon detox water were top recommendations I kept seeing. Learning that Tylenol specifically inhibits this hard-working body process really drove home why we should be cautious about casual use.

Let's look at our over-the-counter pain relief options for children:

Tylenol: Diminishes glutathione (our detoxifying pathway) and causes the body to hold in toxins

Motrin: Not approved for babies under 6 months

Ibuprofen: Causes ulcers, not approved for babies under 6 months

The timing of Tylenol's rise is telling. In the early 1980s, evidence emerged linking aspirin to Reye's syndrome—a rare but serious condition causing brain and liver swelling. Johnson & Johnson representatives, armed with free samples and literature about aspirin's dangers, essentially replaced aspirin with Tylenol for fever and pain in pregnant women and small children. These medications were then routinely given just before vaccines, with parents urged to use them afterward—especially after the pertussis vaccine, which was notorious for high fevers and seizures.

What the research shows:

A 2008 study compared 83 children with autism to 80 without. Children who took Tylenol after the MMR vaccine were significantly more likely to have autism than those who didn't. Children aged 12-18 months were 8-20 times more likely to have autism than children given ibuprofen or no painkiller at all.

Research from the 1980s on lab animals showed that acetaminophen, especially in the presence of testosterone (meaning boys are more vulnerable), can cause mitochondrial disruption and depletion of glutathione. Interestingly, children with autism consistently have lower than normal glutathione levels.

A 2014 Danish study of 64,000 mothers and children found that acetaminophen use during pregnancy (not ibuprofen) was associated with significantly higher risk of ADHD in their babies. The more they took during pregnancy, the more likely their children were to have severe attention problems and hyperactivity—a dose-dependent relationship.

One particularly striking finding: long term downstrem effects of circumcision only saw issues with children who were given tylenol after the surgery.

The Cuban comparison is especially interesting. The highest estimate for autism in Cuba is 185 cases out of 11 million people (0.00168%), compared to as high as 1.5 million out of 300 million Americans (0.50%). That's a rate 298 times higher in the US than Cuba, despite Cuba being economically challenged with income per person 8 times less. One key difference: prescribing acetaminophen as fever prevention with vaccines is common in the US but not in Cuba.

Red flag warning: When any doctor says there is NO evidence contrary to something like this, that's not proof of safety. Plus, there IS evidence—they just haven't read it. At best, all anyone can say for certain is they have not read the research.

Acetaminophen is now the leading cause of acute liver failure in the US, and randomized studies show it's not even that effective as a pain reliever. It's found in over 600 over-the-counter and prescription medications, yet we continue to give it casually to the most vulnerable—pregnant women and small children—often right alongside other interventions without studying the combined effects.

Summary: The Real Science

Tylenol (the better known term used to talk about acetamenaphine) is toxic to growing baby’s liver and depletes glutathione, nature’s mop to clean up toxins.

These are our over-the-counter pain killing options:

Tylenol: diminishes glutathione, (aka our detoxifying pathway), and causes the body to holds in toxins

(vaccines should be considered toxins, since they have heavy metals like aluminum and mercury, and other preservatives known to cause human harm, and are not meant to stay in the body. safety studies assume swift removal, with working detox pathways)

Motrin: not approved for babies <6m

Ibprofin: causes ulcers, not approved for babies <6m.

Red flag #1: When a doctor says there is NO evidence contrary to vaccines. No evidence is NOT proof of safety. Plus, THERE IS EVIDENCE, they just haven’t read it. At best, all anyone can say for certain is they have not read the research.

Understanding How Tylenol Works in the Body

Here's what really concerns me about how Tylenol works: it puts a heavy load on our body's main detoxification system, specifically something called glutathione. Glutathione is like our master antioxidant—its job is to grab onto waste products and toxins and help flush them out. When your body processes acetaminophen, it can use up your glutathione reserves temporarily. If that main detox pathway is busy or depleted because of Tylenol, other toxins that your body would normally clear out might hang around longer.

This became personal for me when I was dealing with adult acne. Glutathione support and morning lemon detox water were top recommendations I kept seeing. Learning that Tylenol specifically inhibits this hard-working body process really drove home why we should be cautious about casual use.

I've read that Tylenol holds in toxins (prevents elimination), so if given during vaccines in kids, it causes the heavy metals to stay in longer. Safety studies are not performed as vaccines are given in real life—in combo, often with Tylenol. Also, in a study on circumcision, the only children long-term with any negative side effects were those who took Tylenol for pain after. I can go on.

A Personal Wake-Up Call

My dad's recent experience really drove this home for me. During his cancer treatment, he was taking Tylenol regularly for pain management—maybe a little too much, as he put it. His blood tests went south, and doctors became concerned about liver damage. He even needed additional liver testing. Once he stopped taking the Tylenol, everything returned to normal.

This made me realize something crucial: if acetaminophen can threaten an adult's liver during treatment, what is it doing to a developing baby's liver? Or a small child's?

The Liver Connection: Why This Matters for Our Smallest Humans

Acetaminophen is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States. Think about that for a moment. The medication we casually give to pregnant women and infants is the number one cause of acute liver failure in our country.

My dad's experience really drove this home for me, but it also sparked a deeper realization about how we treat our liver—our body's major detoxification organ. We know the liver processes alcohol, and we know that when we drink too much, we get headaches. What do many people do for those headaches? Take Tylenol. Think about the irony: we're overburdening our detox organ with alcohol, then adding more toxins (acetaminophen) when our liver is already compromised and trying to recover.

Dr. Ke-Qin Hu, a leading liver disease specialist, warns that severe damage can occur if people take more than four grams of acetaminophen in 24 hours. But here's the kicker: "And that's very conservative, because if taken with alcohol, even two grams can cause problems." Two grams is just four regular-strength Tylenol tablets.

Here's what makes this especially concerning for children and developing babies:

Developing livers work differently. Babies and young children have immature liver enzyme systems. The pathways that adults use to safely process acetaminophen aren't fully developed yet. This means more of the drug gets converted to the toxic NAPQI metabolite that causes damage.

The escalating risk factor. What many people don't realize is that repeated acetaminophen use actually increases the CYP2E1 enzyme—the very enzyme that creates the toxic NAPQI metabolite. It's like your body ramps up the factory that makes the poison. Each time you take it, it could potentially be riskier, not safer.

Smaller bodies, same doses. We often give children doses that, relative to their body weight, are much higher than what we'd give adults. A "children's dose" can put disproportionate stress on a tiny liver that's still learning how to do its job.

The vaccine timing concern. Here's where this gets particularly relevant to the vaccine discussion. The concept of a vaccine is that we know it contains toxic particles (like aluminum), but we trust that our bodies can remove them within a certain timeframe. However, if we compromise the detox pathway with Tylenol at the same time, those toxins may stay in the body longer. We're essentially asking the liver to handle multiple toxic loads simultaneously when it's least equipped to do so.

Cumulative effects we don't track. When we give Tylenol repeatedly—before vaccines, after vaccines, for teething, for any discomfort—we're asking an immature liver to process a compound that overwhelms even adult livers when used regularly.

The glutathione factor. Children already have lower glutathione reserves than adults. When acetaminophen depletes these reserves further, it's like removing the fire department while the house is burning.

My dad's liver recovered because he was an adult with a fully developed detoxification system, and he stopped taking the medication. But what about the developing liver of a fetus whose mother takes Tylenol throughout pregnancy? What about the tiny liver of a baby given Tylenol routinely with vaccines?

If you're harming your liver, you're harming your detox pathways. And if you're harming your detox pathways during critical developmental windows, the consequences could extend far beyond what we see immediately.

This isn't to scare anyone away from necessary medication. If you have a 104-degree fever, that's a medical emergency where the benefits clearly outweigh potential risks. But it made me think: if we're giving something "like candy" without considering cumulative effects, maybe we should pause and ask more questions.

The Broader Picture: Everyday Products We Don't Question

This brings up a broader point about everyday products we use without thinking. Take Tums, for example—something many pregnant women reach for during those brutal final months of acid reflux. Dr. Mark Hyman discusses how antacids like Tums can seriously mess up our microbiome and acid profile, which is especially concerning when you're building a baby who depends on your gut health.

Or think about lotion ingredients and perfumes. We put fragrances directly on our necks—often even while breastfeeding—without considering that these chemicals are being absorbed through our skin and potentially affecting our children through skin contact or breast milk.

The point isn't to become paranoid about everything, but to recognize that many seemingly harmless things we use casually might deserve more thoughtful consideration, especially during pregnancy and early childhood when systems are developing.

Why We Can't Just Wait for Our Doctors

This isn't about rejecting medical advice—it's about being informed participants in our healthcare decisions. We hire our doctors. They are busy. I believe they are good people, but they are stuck often in an insurance hamster wheel that gives them 5 to 15 minutes with patients. We should not be waiting on our overworked doctors to be getting educated on new science. We would love to, but in reality, they don't have time to unravel the insurance model that pays them. The reality is our healthcare system is incentivized to have patients for life.

We are finally emerging to a point where we own our data. Our doctor can sign off on us getting a blood test, but we can get infinite opinions on how to interpret that data—even to know what blood tests to take! Insurance models do not let us use our insurance money on prevention. That is not good for their bottom line. They don't want to spend money on us looking to see if we can prevent issues before they become real problems (like vitamin and hormone imbalances that are easy to check).

For example, I was interested in having children, and wanted a full blood panel to know my nutrient status, since many things are needed to build a baby's spine and brain and body. My doctor said I would need to have 3 miscarriages to be able to use my insurance money to get the blood tests I was requesting. I was not asking him to interpret them—I was just asking him to OKAY my want to get my blood examined, to take it elsewhere and interpret it myself based on easy-to-find information on what babies need.

This is all to say there are many examples where we need to do this ourselves. Doctors are great for taking care of sick people. But I want to be a vibrant person. I want my children to be given the best opportunity possible. I was never okay not getting A's. I want to get 100% on everything I do, and if I can do something to provide a better starting base for my kids, then I give a damn if someone, anyone, says that we should be cautious with drugs with our kids.

Prevention vs. Treatment: Where We Put Our Energy

When we talk about prevention and lifestyle factors, we're not dismissing the complexity of health conditions or blaming anyone. We're acknowledging that some risks might be modifiable—and that's actually empowering.

The statistic that troubles me most: today, 1/3 of all cancers are found to be related to lifestyle choices. One-third of all cancers would disappear if we made changes we know about. But less than 1% of cancer funds are spent on educating the public on things like this. (Not saying cancer is related to Tylenol, but this falls in the education bucket.)

I think the nurse mom's point was that our research dollars should be put more toward cancer research instead of questioning things like Tylenol. But I disagree. Not enough money is spent on educating the public how they can take control of their health now. Today. The current approach puts too much emphasis on the hope for a pill that will cure ALL KINDS of cancer in ALL KINDS of people, which the science says is not that simple.

We need to work on the upstream end to get out of being pummeled by the wave of needing immediate care, rather than just waiting until we're drowning and then trying to stop it from happening. We each have different toxic loads and burdens and reactions to those specific things—whether food or pollution or whatever stress. We need to learn about ourselves, as well as the things that are bad for everyone. We need to learn there are tools to use when needed, but should not be abused, and should be warned of overuse. Strongly.

Think about it this way: if there was a pill that cured 1/3 of all cancer today, it would be negligent to not prescribe it. Instead, we say, "everything causes cancer" so just go about your day. The stress is not worth the trouble. I disagree wholeheartedly. It is an uphill battle, but as with every hike, it takes just one step in front of the other. And it helps if you have others with you supporting you as you go.

Statistically, we individually are more powerful than waiting on an insurance-modeled system to find the cure. There will be no one bullet for cancer—there are infinite kinds and varieties. But of course, good progress has been made on removing it once we have it. Prevention is a huge part being dismissed.

And here's the thing about Tylenol specifically: it's temporary pain relief that hardly works. If there's science telling us it can do harm to children, in any possible way, ditch it until we know better.

Using Big Data for Individual Health Decisions

And while we have this "big data" problem—too much information to reasonably sort through—we also have resources to help us navigate it all better than ever before. We should put all that data to work, studying in detail all the tiny things and products we individually use and see how everything correlates. Some companies are already doing this, especially related to children's health, asking detailed questions about parents' and grandparents' histories—what toothpastes they used, how they did their hair, what foods they ate, how births went. These kinds of details help us in the long run, because our technology can do the number-crunching work we could never do before, aggregating this information into actionable insights.

The reality might be that during those 9 months of pregnancy—which are often very tough on women—we may just have to tough it out without the Tylenol and Tums. Maybe we'll be very thankful for that choice 9 or 90 years later.

What Does Appropriate Caution Look Like?

For me, appropriate caution means really having conversations with ourselves and our healthcare providers. Is this a minor headache that might pass in an hour, or is this a situation where pain relief is genuinely necessary? What does my doctor think about the emerging research? Are there alternatives for minor discomfort that I haven't considered?

It means thinking about cumulative effects. Regular use is different from occasional use during genuine need. It means staying informed about evolving research while working with trusted medical professionals who are willing to have real discussions about risk and benefit.

Moving Forward

Nothing should be off-limits for discussion when it comes to our children's health. This isn't about fear-mongering or rejecting modern medicine. It's about having honest conversations, asking good questions, and making thoughtful decisions for our families.

It's not blame. It's understanding there are things we can do, and that is power. We should all educate ourselves on ways to help when possible.

In case anyone is interested, I have a full blog on this, and vaccines, on my personal site. I am shy, and don't like to share my opinions, but a few things we should all know: take Tylenol ONLY if you really think you need it. Try to separate children's vaccines so they are not getting mega doses at once in things not studied as administered, and do not give to kids when sick. That's about it. Nothing is off the table. We are allowed to talk about this. It is not voodoo. My kids are totally vaccinated—I just did so while 100% informed.

Our children deserve nothing less than our most informed, thoughtful care.

This is not about rejecting medicine. It’s not about demonizing Tylenol or “blaming moms.” It’s about informed choice. It’s about asking questions and refusing to accept outdated, oversimplified assurances when emerging research raises legitimate concerns.

For me, the takeaway is simple:

Use Tylenol only when truly necessary.

Don’t pair it casually with vaccines or minor discomfort. (this is when side effects seem to mutiply)

Just to throw in, while I have your attention (on broader vaccine research):

Do not allow your child to get a vaccine when they are sick (side effects multiply again)

If you are a parent to a boy, or african american child, or a child with kidney issues, look up MMR vaccine issues and read about things that reduce adverse side effects. Some of those include separating vaccines out to individual doses, and pushing the vaccine out 6+ months from the typical recommendation in CA of 18 months old to help reduce documented adverse side effects in these higher risk groups.

Our children deserve nothing less than our most informed, thoughtful care.

This is my perspective as a parent. It is not medical advice. Always consult qualified healthcare professionals for decisions about your family’s health.

The truth is, we need more research. What we have is not enough. We are not yet certain or sure about any proven links of anything, so anyone claiming DISPROOF is claiming more than they are possibly able.

We cannot claim determinism or not, but we have seen there is a slight chance of increase of risk. We know for sure there is a potential auto immune issue that a mother can express as an antibody. We can now create a well funded study to get to core of the issue.

On the off chance that there is determinism, we should err on the side of caution. The truth is the appropriate safety studies have not been completed. There may be several paths to autism. Maybe there is a 0.05% chance of increase of some issue from one thing, but if you stack that up, and understand it is in combination with a cumulative effect of many more new things in our environment (in the last 100 years), there is reason to be concerned. Most studies are organized around short duration, high exposure. But the cumulative, long term exposure, is starting to present as a real problem, as we have seen with microplastics and endocrine disruptors that can block expression of proteins. Plastics are only now starting to be looked at after 70 years breaking down in our environment and water supply and brains and hearts, true of every novel item we have made. Some things persist, some break down, but there is a cumulative effect that add up and increase probability of things like DNA breaks that do result in cancer, or damage to folate receptors that drive autism spectrum disorder.

Asking these questions is incredibly important. This cannot be just a political point. As scientists, we have to continually interrogate for answers. It is great to question these things and not give the medical industrial complex a pass on all this.

I have also heard that this is not an important issue. Tylenol or autism. I would disagree. It is one drop in a bucket, and not a minor one. The emotional burden on a parent is one thing, but the total annual spend in the U.S. on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was $268 billion in 2015, increased expected as $461 billion by 2025, and is only expected to get much higher in future decades if effective prevention and intervention strategies are not established.

This post reflects my personal perspective and experiences. It is not medical advice. Always consult with qualified healthcare providers about medical decisions for you and your family. Don’t be afraid to ask questions or do your own research. Nobody will fight for your family more than you.

Resources

On the Dangers of Acetaminophen

This is a comprehensive research paper by William Shaw (2013) that proposes acetaminophen (Tylenol) as a major cause of the autism, ADHD, and asthma epidemics. Here's a summary of the key arguments:

Core Hypothesis

Shaw argues that increased acetaminophen use in genetically vulnerable children and pregnant women is largely responsible for rising rates of autism, ADHD, and asthma since the 1980s.

Key Evidence Presented

Timing Correlation:

The switch from aspirin to acetaminophen in the 1980s (due to Reye's syndrome concerns) coincided with rising autism/ADHD/asthma rates

Cuba has dramatically lower autism rates (298x lower than the US) and rarely uses acetaminophen prophylactically with vaccines

Biological Mechanisms:

Acetaminophen depletes glutathione, the body's master antioxidant and detoxification system

Creates toxic metabolite NAPQI that causes oxidative damage

Particularly harmful when combined with vaccines, as it may prevent elimination of heavy metals

Causes specific brain cell death (Purkinje cells) seen in autism

Research Findings:

2008 study: Children taking acetaminophen after MMR vaccine were 8-20x more likely to develop autism than those given ibuprofen or nothing

2014 Danish study: Prenatal acetaminophen linked to ADHD in dose-dependent manner

100% of autistic children in one study had unique lung abnormalities vs. 0% of non-autistic children

Manufacturing Issues:

Decade-long quality control problems with acetaminophen products

Contamination with bacteria and chemicals

Mislabeling leading to overdoses

Critical Assessment

Strengths:

Presents extensive biochemical research on acetaminophen toxicity mechanisms

Identifies interesting correlations (timing, geographic differences)

Cites legitimate peer-reviewed studies

Limitations:

Primarily correlational evidence - correlation doesn't prove causation

Cuba comparison has many confounding variables beyond acetaminophen use

Small sample sizes in some key studies

Relies heavily on parental recall for medication history

Many studies cited don't directly support the autism connection

Scientific Standing: This represents a hypothesis that has generated some research interest but hasn't been widely accepted by mainstream medical organizations. The acetaminophen-asthma connection has stronger research support than the autism connection. The paper calls for large-scale studies to test these hypotheses properly.

The author presents this as urgent public health concern requiring immediate caution with acetaminophen use, particularly around vaccination times and during pregnancy.

Key scientific details that strengthen your argument:

The sulfation pathway deficiency - Shaw explains that people with autism have defective sulfation pathways (phenolsulfotransferase deficiency), which makes them particularly vulnerable to acetaminophen toxicity. This provides a biological explanation for why some children are more susceptible.

The CYP2E1 enzyme induction - Repeated acetaminophen use actually increases the enzyme that converts it to the toxic NAPQI metabolite, meaning each exposure becomes more dangerous. This explains why prophylactic use before vaccines is particularly concerning.

The fasting/illness vulnerability - Shaw notes that acetaminophen is much more toxic when children are fasting or ill (which often happens during vaccine visits), because this increases the toxic pathway while decreasing glutathione production.

The lung findings - Dr. Barbara Stewart's discovery that 100% of autistic children had unique lung abnormalities (doubled airway branches) versus 0% of controls is striking evidence that connects the asthma and autism epidemics.

The manufacturing contamination - The decade of quality control problems, bacterial contamination, and mislabeling that led to overdoses adds another layer of concern about what children were actually receiving.

Personal Notes from own research

Here are my fully pasted notes from studies on the harms of Tylenol:

Connects the increased in autism and other issues with pregnant and pediatric use of acetaminophen, which disrupts the body’s ability to rid itself of toxic chemicals.

The marked increases in these disorders in the United States coincides with the replacement of aspirin by acetaminophen (Tylenol) in the 1980s.

People with autism have a characteristic loss of certain kinds of brain cell (Purkinje cells, some of the largest neurons in the human brain). Overuse of Tylenol causes reduction in glutathione levels in the brain, leading to the same brain cell death seen in autism.

number of Purkinje cells in autistic patients were

15 standard deviations below the mean in one part of the brain,

and 8 standard deviations below the mean in another hemisphere

one of these cerebella also showed an almost complete loss of Purkinje cells from the its cell layer, and susceptibility of these cells to oxidative stress during GSH depletion

Hair mercury concentrations of children with autism are consistent with those taking acetaminophen.

Acetaminophen toxicity may overload a certain pathway, which is already deficient in autism, leading to overproduction of toxins WITH reduced ability to remove toxins, creating more [oxidative] stress and [free radical] damage.

On top of that, major problems in acetaminaphen production led to concentrations much higher than listed on the label, and bacteria contamination, meaning kids getting overdosages of acetaminophen and toxic bacteria for as long a decade.

Making a connection between disease appearance and causative agent is important.

We got better at some things, esp with stuff like knowledge of DDT toxicity (and the fight of one woman single handedly):

acceptable safe limits for levels of lead in the blood have decreased

from 60 μg/dL in 1960

to <5 μg/dL in 2010

One of the most notable cases of serious adverse effects caused by a pharmaceutical agent was the terrible developmental epidemic of the birth of children with seal-like arms and legs (phocomelia) that was linked to the maternal use of the sedative thalidomide 20–35 days after conception. What would have happened if the thalidomide connection had never been made?

One of the difficulties with chemical studies of autism associations is that most chemicals are used worldwide, making it difficult to find a “clean” environment where autism might be less prevalent. One of the clues that led to the discovery of thalidomide as the causative agent of deformed limbs was that it was much more commonly used in Europe than in the United States.

We can actually see this in Cuba. The highest estimate of the total incidence of autism in Cuba is 185 cases out of a total population of 11,000,000 (0.00168% of the population) compared with an estimate of as high as 1.5 million in a total United States population of 300 million (0.50%). This means the rate of autism in the United States is 298x higher in the US than in Cuba, though much more economically challenged, income per person 8x less.

what we can look at here are at other factors around the vaccine, like prescribing acetaminophen as a fever preventative (used in US, not in Cuba).

children with autism had more adverse reactions to the MMR vaccine and were more likely to have been given acetaminophen than ibuprofen for those reactions. Compared with controls, children aged 1–5 years with autism were eight times more likely to have become unwell after the MMR vaccine, and were six times more likely to have taken acetaminophen. Children with autism who regressed in development were four times more likely to have taken acetaminophen after the vaccine. Illnesses concurrent with the MMR vaccine were nine times more likely in autistic children when all cases were considered, and 17 times more likely after limiting cases to children who regressed. There was no increased incidence of autism associated with ibuprofen use.

Direct, drug-induced harm accounts for only part of the overall syndrome of acetaminophen-induced liver injury.

During the immune response, invading inflammatory cells release toxic oxidants and cause a second wave of destruction, equal in damage to the first attack.

It has been speculated that frequent use of acetaminophen might influence asthma and rhinitis by depleting levels of reduced GSH in the nose and airways, thus shifting the oxidant/antioxidant balance in favor of oxidative stress and increasing inflammation.

Acetaminophen decreases GSH levels, principally in the liver and kidneys, but also in the lungs. These decreases are dose dependent

Higher levels of IgG, IgA, and IgE allergies to various foods have been reported in children with autism, together with abnormal cellular immune responses to milk, wheat, and soy.

It has been shown that depleting GSH in the brain induces a neuro-inflammatory response that results in significant release of cytokines and other material toxic to neurons

The beginning of the rapid increase in autism in around 1980 coincides with the rapid increase in asthma, both of which coincide with the rapid increase in the use of acetaminophen following the Reye’s syndrome scare over a possible association with aspirin

2011, Barbara Stewart, a pediatric pulmonologist, found a significant lung abnormality was present in 100% of children (n = 47) on the autistic spectrum examined, but in none of >300 children without autism. She noticed during lung examinations, that, although the airways of the children initially appeared normal, the lower airway had doubled branches that should have been singles.

As of 2012, 145 studies had shown an association between mitochondria function and autism.

Articles:

A 2014 Danish study of 64,000 mothers and children found that acetaminophen use during pregnancy (not ibuprofen) was associated with significantly higher risk of ADHD in their babies. The more they took during pregnancy, the more likely their children were to have severe attention problems and hyperactivity—a dose-dependent relationship.

“a dose-response effect was noted as increasing use of the medication increased the likelihood of neurological problems.”

FINAL CONCLUSIONS

Using prospective data from a well-designed large cohort of pregnant women with a long duration of follow-up and registry-based outcome assessment, we found that prenatal exposures to acetaminophen may increase the risk in children of receiving a hospital diagnosis of HKD or ADHD medication and of exhibiting ADHD-like behaviors, with higher use frequency increasing risk in an exposure-response manner.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24566677/....

Acetaminophen use during pregnancy, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders - PubMed • pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Research from the 1980s on lab animals showed that acetaminophen, especially in the presence of testosterone (meaning boys are more vulnerable), can cause mitochondrial disruption and depletion of glutathione. Interestingly, children with autism consistently have lower than normal glutathione levels. https://www.researchgate.net/.../51218639_Sex_difference...

A 2008 study compared 83 children with autism to 80 without. Children who took Tylenol after the MMR vaccine were significantly more likely to have autism than those who didn't. Children aged 12-18 months were 8-20 times more likely to have autism than children given ibuprofen or no painkiller at all. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18445737/

My Article: On the Potential Harm of Tylenol in Babies and Pregnant Women

My Article: On Childhood Vaccines, A comprehensive Study