Reading from an Arabic text on the Emperor Nero from a time of lost (and manipulated history)… I came upon something incredibly surprising. Read for yourself.

Research on Nero in Bishop of Nikiu

Page 52:

“Chapter LXX. 1. And, after the death of Claudius, the abominable Nero became emperor in Rome. Now he was a pagan and an idolater. 2. And to his other vices he added the vice of sodomy, and he, married as though he were a woman. And when the Romans heard of this detestable deed, they could no longer endure him. 3. And the idolatrous priests particularly inveighed against him, and the senators elders of the people) deposed him from the throne 2 and took counsel in common to put him to death. And when this impure wretch was informed of the purpose of the senators, he quitted his residence and hid himself. But he was not able to escape the mighty and powerful hand of God. 4. For when he fell into this disquietude of heart, owing to the debauchery which he had practised as a woman, owing to this cause (I repeat) his belly grew distended and became like that of a pregnant woman. 5. And he was greatly afflicted by the multitude of his loathsome pains. And therefore he ordered the wise men to visit him in the place where he was (hidden), and to administer remedies. 6. And when the wise men came to him thinking that he was with child, they opened his belley in order to deliver it. And he died by this evil death.

Then it goes right into the next Emperor:

“Chap LXXI 1. And after the death of Titus Domitian his brother became emperor in his stead. And he was a great philosopher among the heathen...”

This made me research what we know about Nero!! Could this Arabic document hold a secret about a much-hated Roman emperor???

Per Google, it says, no way. “The Roman emperor Nero did not die from surgery to his belly. He committed suicide by stabbing himself in the throat with a dagger. The act was reportedly assisted by his private secretary, Epaphroditus, after Nero, declared a public enemy by the Senate, lost his nerve to do it himself. In the lead-up to his death in 68 CE:

The Senate had condemned him to death, and the Praetorian Guard had abandoned him.

He fled Rome and took refuge in a villa outside the city.

Upon hearing that soldiers were approaching to arrest him, Nero decided to take his own life to avoid public execution.”

But this hardly means the case is closed. The circumstances surrounding Nero's death included dramatic elements. Historian Suetonius recorded Nero's final words as "Qualis artifex pereo," which means, "What an artist dies in me!".

The Hidden Emperor: A Thought Experiment on Gender, Power, and Suppressed History

What if one of Rome's most notorious rulers was actually hiding the greatest secret of all?

The Arabic Account: A Window into Lost Truth?

Bishop John of Nikiou's 7th-century chronicle presents a startling account of Emperor Nero's death that diverges completely from Roman sources. Rather than suicide by dagger, John describes Nero as someone who "practiced debauchery as a woman," developed a belly "like that of a pregnant woman," and died when physicians attempted to "deliver" what they believed was a child.

Could this seemingly outlandish account preserve a kernel of historical truth that Roman sources systematically erased?

The Historical Context for Such Deception

Rome's Misogyny Made Female Rule Impossible

Roman society was intensely patriarchal. Women couldn't hold political office, command armies, or rule in their own right. The very concept of female imperial authority was anathema to Roman political culture. Any woman seeking ultimate power would have faced insurmountable obstacles - unless she could successfully present as male.

Precedents Existed for Gender Deception

The legend of Pope Joan, whether historical or mythical, demonstrates that medieval minds could conceive of a woman successfully maintaining male identity in the highest positions of power for years. If such deception was imaginable in the religious sphere, why not the political?

The Julio-Claudian Women Were Extraordinarily Powerful

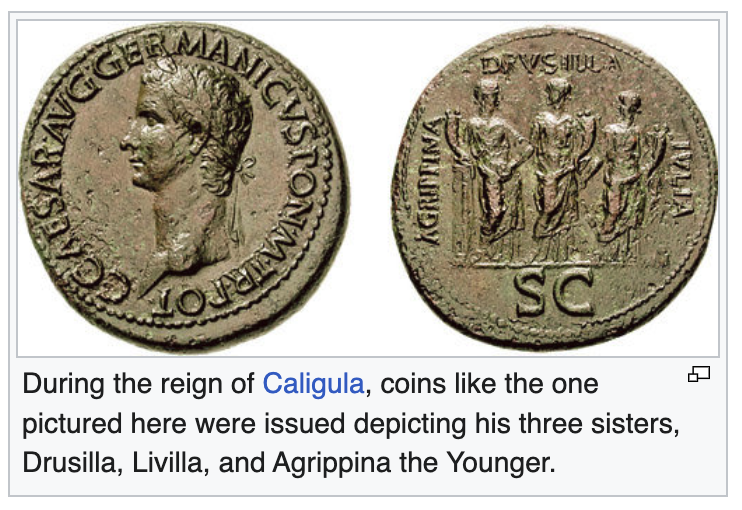

Agrippina the Younger wielded unprecedented influence, appearing on coins, receiving divine honors, and acting as co-ruler with Claudius. She had both the motivation and capability to orchestrate an elaborate deception to place her child on the throne.

Reconstructing a Possible Scenario

Early Years: The Foundation of Deception

If Nero was born female, Agrippina would have faced an immediate crisis. Her child's claim to succession depended entirely on being male. The solution? Present the child as male from birth, possibly with the help of carefully chosen household staff and physicians.

Key supporting evidence:

Domitius's alleged comment that nothing from him and Agrippina "could possibly be good for the state" - perhaps reflecting knowledge of the deception rather than prophecy

The snake-skin bracelet incident during childhood - possibly a cover story to explain why assassins left without examining the child closely

Agrippina's careful control of the household, removing anyone loyal to previous regimes who might discover the secret

Adolescence: Maintaining the Illusion

Historical accounts note that Nero was kept away from public scrutiny during crucial developmental years. If biologically female, puberty would have required increasingly elaborate measures:

Private tutoring with carefully vetted instructors like Seneca

Limited public appearances during adolescent years

Possible use of binding or other concealment methods

Careful management of marriage arrangements

The Marriage Problem

Nero's marriage to Octavia at age 16 would have presented enormous challenges. The marriage was reportedly unhappy and produced no children despite lasting 13 years. If Nero was female:

The lack of consummation could be explained by "impotence" or other medical excuses

Octavia's eventual execution might have been necessary to prevent her from revealing the truth

The subsequent marriage to Poppaea, who died in circumstances suggesting domestic violence, could indicate escalating desperation to maintain the deception

Medical Possibilities

Several conditions could produce symptoms resembling pregnancy in someone assigned male at birth:

Intersex Conditions: Various chromosomal or hormonal variations could result in ambiguous genitalia, potentially allowing someone with XX chromosomes to be initially identified as male.

Pseudocyesis (False Pregnancy): Psychological conditions can produce physical symptoms of pregnancy, including abdominal distension and cessation of menstruation.

Hormonal Disorders: Conditions affecting hormone production could cause unusual physical development and symptoms.

Abdominal Tumors: Various growths could cause the "distended belly" described in the Arabic account.

The Support Network

Such an elaborate deception would require extensive cooperation:

Agrippina's Role: As the architect of the scheme, she systematically eliminated potential threats and maintained control over access to her child.

Household Staff: Trusted slaves, freedmen, and servants who were bound to the family and could be relied upon for secrecy.

Medical Conspirators: Physicians who could provide cover stories for various physical necessities and treatments.

Political Allies: Senators and administrators who benefited from the arrangement and had incentive to maintain it.

Why Roman Sources Would Suppress This

Political Necessity: Admitting a woman had ruled Rome would have been politically catastrophic, potentially invalidating every law, decree, and military action of the reign.

Religious Implications: Roman religion was deeply tied to male authority. A female emperor would have raised fundamental questions about divine approval.

Masculine Honor: The very concept would have been so emasculating to Roman identity that complete suppression would have been essential.

Precedent Concerns: Acknowledging successful female rule might inspire other women to attempt similar deceptions.

The Arabic Preservation

Why might this truth survive in a Coptic Egyptian source?

Cultural Distance: Egyptian Christianity had different attitudes toward women in religious authority, making the account less shocking to preserve.

Alternative Information Networks: Trade routes and diplomatic contacts could have carried rumors and stories outside Roman control.

Religious Framework: Christian authors might have seen divine justice in the "unmasking" of a pagan ruler's deception.

Time and Translation: The story might have been preserved as curious historical anecdote rather than politically sensitive information.

Modern Implications

If this thought experiment has merit, it would fundamentally alter our understanding of:

Roman History: The entire Neronian period would need reassessment through a different lens.

Gender and Power: It would provide a remarkable example of how gender restrictions could be circumvented through elaborate deception.

Historical Methodology: It would demonstrate the crucial importance of examining sources outside dominant cultural traditions.

Modern Parallels: It might offer insights into contemporary questions about gender identity and presentation.

Conclusion: The Power of Alternative Perspectives

Whether or not Nero was biologically female, this thought experiment illuminates several crucial points:

The systematic suppression of alternative historical sources has created artificial certainties about the past. Arabic and other non-Roman sources preserved different perspectives that challenge dominant narratives, just as we've seen with medieval Arabic Egyptology.

The possibility that a woman could have successfully ruled Rome while presenting as male would represent one of history's most audacious deceptions - and would help explain why Roman sources went to such lengths to demonize and distort Nero's legacy.

Most importantly, it demonstrates how power structures shape historical narratives, and why seeking out suppressed voices and alternative sources remains essential for understanding the complexity of the past.

The truth about Nero may be lost forever, but the Arabic account reminds us that history is far more complex and contested than dominant narratives suggest. Sometimes the most important truths survive in the most unexpected places.

Timeline: Nero's Life and the Politics of Historical Memory

Background: Memory Manipulation Across Cultures

Egyptian Royal Memory Control (3100 BCE - 30 BCE)

Egypt pioneered systematic historical revision millennia before Rome:

Cartouche destruction: Royal names chiseled from monuments

Monument usurpation: Later pharaohs claimed credit for predecessors' buildings

Historical rewriting: Official king lists omitted "unworthy" rulers

Religious justification: Divine pharaoh concept made memory control essential

Egyptian Precedents for Historical Erasure

Hatshepsut (c. 1479-1458 BCE) - The Erased Female Pharaoh

1479 BCE: Becomes regent for young stepson Thutmose III c. 1473 BCE: Assumes full pharaonic titles and regalia

Depicted herself with false beard and male royal clothing

Ruled successfully for ~15 years with economic prosperity

1458 BCE: Dies (natural causes likely) c. 1440s BCE: Systematic erasure begins under Thutmose III

Her cartouches chiseled out and replaced with Thutmose I, II, or III

Statues smashed and buried

Obelisks walled up to hide her inscriptions

Official king lists omitted her entirely

Modern rediscovery:

1822: Champollion first identified her cartouches

1903: Howard Carter discovered her sarcophagus

2007: Her mummy possibly identified through DNA

Assessment: One of most successful pharaohs, erased for being female

Akhenaten (c. 1353-1336 BCE) - The Heretic Pharaoh

c. 1353 BCE: Becomes pharaoh as Amenhotep IV Year 5: Changes name to Akhenaten, establishes monotheistic Aten worship c. 1348 BCE: Moves capital to new city Akhetaten (Amarna)

1336 BCE: Dies; immediate successors begin reversing reforms Under Tutankhamun and Horemheb: Systematic erasure

Akhetaten abandoned and dismantled

Aten temples destroyed, stones reused

Akhenaten's cartouches hammered out

Called "the enemy" or "the criminal" in later texts

Omitted from official king lists

Modern rediscovery:

1880s: Amarna site excavated

1922: Tutankhamun's tomb provides indirect evidence

20th century: Gradual reconstruction of Amarna period

Nefertiti (c. 1353-1336 BCE) - The Vanished Queen

Evidence of power: Depicted in pharaonic regalia, possibly co-ruled with Akhenaten Mysterious disappearance: Vanishes from records around Year 12 of Akhenaten's reign Theories:

Died naturally

Became co-pharaoh under different name

Fell from grace and was erased

Erasure: Subject to same damnatio memoriae as Akhenaten Modern status: Famous bust discovered 1912, but life remains largely mysterious

Earlier Female Rulers

Merneith (c. 2950 BCE):

Not first female pharaoh (this is incorrect)

Mother/regent during early Dynasty I

Possibly ruled briefly but evidence limited

First definitively female pharaoh: Neithhotep (c. 2850 BCE) or possibly later

Sobekneferu (c. 1806-1802 BCE):

Last ruler of 12th Dynasty

Clearly depicted as female pharaoh with mixed male/female regalia

Brief 4-year reign

Later king lists largely omit her

Background: Damnatio Memoriae in Roman Culture

Origins and Practice (509 BCE - 476 CE)

509 BCE: Roman Republic established; early forms of memory sanctions begin against traitors

1st Century BCE: Practice formalized during late Republic to punish enemies of the state

Imperial Period (27 BCE - 476 CE): Approximately half of all Roman emperors suffered some form of damnatio memoriae

Purpose: Erase political enemies from public memory through destruction of images, names, and records

Notable Imperial Victims Include:

Caligula (41 CE) - partial

Nero (68 CE) - extensive

Domitian (96 CE) - severe

Commodus (192 CE) - later reversed

Nero's Life Timeline

37 CE - Birth and Early Childhood

December 15: Born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in Antium

Sources: Suetonius (c. 121 CE) - written 50+ years after death

Reliability: LOW - Suetonius known for scandalous, unverified anecdotes

Father's alleged prophecy: Domitius supposedly said nothing from him and Agrippina "could possibly be good for the state" (highly speculative - likely post-facto propaganda)

Mother Agrippina: Descendant of Julius Caesar, extremely ambitious

Egyptian parallel: Royal mothers crucial for legitimacy (like Queen Ahmose, mother of Hatshepsut)

Sources: Suetonius (121 CE) - 50+ years later, LOW reliability

Egyptian Context: Female Power and Succession

Egyptian royal women regularly held power behind the scenes:

Queen mothers: Often ruled as regents

Divine wives: Religious positions with political influence

Royal marriages: Sisters/daughters married to legitimize male rulers

Precedent: Multiple female pharaohs successfully ruled in their own right

49-54 CE - Agrippina's Rise to Power

49 CE: Marries Emperor Claudius 50 CE: Son adopted as heir

Agrippina's influence: Appears on coins equal to emperor, holds audiences

Egyptian parallel: Queen Tiye (Akhenaten's mother) wielded similar behind-scenes power

54 CE: Claudius dies, Nero becomes emperor at 16

Agrippina's control: Manages household, removes threatening personnel

Egyptian parallel: Queen Ahmose likely controlled access to young Hatshepsut

54-59 CE - Joint Rule Period

Early reign shows unusual maternal influence:

Agrippina sits beside throne during audiences

Her image appears on currency

She controls palace access and personnel decisions

Egyptian parallel: Hatshepsut began as regent, gradually assumed full pharaonic symbols

59 CE - The Mother's Death

March: Agrippina killed on Nero's orders

Multiple contradictory accounts in sources

Timing significance: Shortly after Nero begins asserting independence

Egyptian parallel: When Hatshepsut died, Thutmose III began her systematic erasure

68 CE - Death and Memory Erasure

June 9: Nero dies by suicide (traditional account) Alternative account: John of Nikiou (680 CE) describes death from "pregnancy" complications

Distance: 600+ years later

Cultural context: Coptic Christian, outside Roman political control

Reliability: Very low, but represents alternative tradition

Immediate damnatio memoriae:

Images destroyed

Names chiseled from inscriptions

Coins melted down

Egyptian parallel: Same techniques used against Hatshepsut, Akhenaten

39-40 CE - Family Crisis

39 CE: Mother Agrippina exiled by brother Emperor Caligula

Accused of adultery and conspiracy (details remain unclear) 40 CE: Father Domitius dies of edema

Child sent to live with paternal aunt

Note: Agrippina separated from child during crucial early years

41 CE - Return from Exile

January: Caligula assassinated; Uncle Claudius becomes emperor Late 41: Agrippina and child return to Rome

Significance: Child reunited with mother around age 4

49-50 CE - The Adoption

49 CE: Agrippina marries Uncle Claudius (considered incestuous by Roman standards) 50 CE: Child adopted by Claudius, renamed Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus

Sources: Tacitus Annals (c. 109 CE) - written 40+ years later

Reliability: MODERATE - Tacitus more reliable than Suetonius but still wrote under different dynasty

Speculation: Agrippina's systematic removal of palace staff who knew previous regime

53 CE - Marriage to Octavia

Age 16: Marries stepsister Claudia Octavia

13-year marriage produces no children

Sources: Multiple but all post-death accounts

Modern assessment: Marriage details likely embellished for political purposes

54 CE - Becomes Emperor

October 13: Claudius dies (possibly poisoned by Agrippina) October 14: Nero proclaimed emperor at age 16

Sources: Contemporary accounts lost; surviving versions from Tacitus, Suetonius

Reliability: MODERATE for basic facts, LOW for motivational details

54-59 CE - "Golden Years" of Reign

Early reign: Guided by mother Agrippina, tutor Seneca, and Praetorian Prefect Burrus

Economic prosperity, diplomatic successes

Sources: Even hostile sources acknowledge this period's success

Note: Success attributed to male advisors in sources, despite Agrippina's documented influence

55 CE - Death of Britannicus

February: Claudius's biological son dies suddenly (age 13)

Allegation: Nero poisoned him

Sources: Tacitus, Suetonius - both writing decades later

Reliability: LOW - Poison detection impossible; convenient accusation for hostile sources

59 CE - Mother's Death

March: Agrippina killed on Nero's orders

Multiple contradictory accounts: Collapsing boat, direct assassination, etc.

Sources: Tacitus (Annals 14.3-9), Suetonius, Cassius Dio

Written: 40-150 years after events

Reliability: LOW for details, MODERATE that she died violently

Speculation: If gender deception theory true, mother's death removes key conspirator

62 CE - Divorce and Remarriage

62 CE: Divorces Octavia, marries Poppaea Sabina 65 CE: Poppaea dies (allegedly kicked while pregnant)

Sources: Hostile accounts from Tacitus, Suetonius

Reliability: LOW - Details likely exaggerated

Note: Pattern of failed relationships with women who might discover secrets

64 CE - Great Fire of Rome

July 19-28: Devastating fire destroys much of Rome

Nero's role: Contemporary sources suggest he organized relief efforts

Later accusations: Started fire to build palace (no contemporary evidence)

Scapegoating: Christians blamed and persecuted

Sources: Tacitus provides most balanced contemporary-adjacent account

65-68 CE - Final Years and Revolts

65 CE: Pisonian conspiracy discovered and suppressed 68 CE: Military revolts in Gaul and Spain

Praetorian Guard abandons Nero

Senate declares him public enemy

68 CE - Death

June 9: Dies by suicide (traditional account)

Location: Villa outside Rome

Method: Dagger to throat with secretary's assistance

Last words: "What an artist dies in me!" (Suetonius)

Alternative account: Bishop John of Nikiou describes death from surgical intervention for "pregnancy"

Reliability of alternatives: VERY LOW - written 600+ years later

Post-Death - Damnatio Memoriae

68-69 CE: Systematic destruction of Nero's images and inscriptions begins Following decades: "False Nero" pretenders appear, suggesting popular support

Extent: More thorough than most imperial condemnations

Survival: Some coins and inscriptions escaped destruction

Comparative Case: Pope Joan (Legendary, 853-855 CE)

First recorded: Martin of Troppau (1277 CE) - 400+ years later Story: Woman disguised as man becomes pope, discovered during childbirth Modern assessment: Mythical - no contemporary evidence

Significance: Shows medieval acceptance that women could successfully maintain male disguise in highest positions

The Legend

Alleged dates: 853-855 CE (Pope John VIII) Story: Woman named Joan allegedly disguised herself as man, became pope, discovered when giving birth during procession Sources: First mentioned by chronicler Martin of Troppau (1277 CE) - over 400 years later Modern consensus: MYTHICAL - no contemporary evidence exists

Why the Legend Emerged

Medieval anxiety about clerical celibacy

Political criticism of papal authority

Folklore motif of disguised women in positions of power

Relevance to Nero theory: Demonstrates medieval minds could conceive of successful long-term gender deception

Source Analysis and Reliability

Nero Source Problems

Contemporary sources: Virtually all lost Later Roman historians:

Tacitus (109 CE): 40+ years later, MODERATE reliability

Suetonius (121 CE): 50+ years later, LOW reliability for personal details

Cassius Dio (220 CE): 150+ years later, VERY LOW reliability

Alternative source:

John of Nikiou (680 CE): 600+ years later, different cultural tradition

Assessment: While extremely distant, represents non-Roman perspective that escaped imperial censorship

Conclusion

While Egyptian examples demonstrate that systematic historical erasure was common in ancient world, and that female rulers could successfully maintain power (whether or not presenting male imagery), the specific theory about Nero's gender lacks any credibility in either direction. The comparison reveals more about how political memory is constructed than about any individual ruler's biology.

The Egyptian parallels do illuminate how thoroughly ruling dynasties could control historical narratives - a practice Rome inherited and perfected. Egypt had precedents for female rule that Rome utterly lacked. This does not mean one woman could not have made it through the cracks…

Contemporary Sources (Lost)

Official court records

Military dispatches

Administrative documents

Problem: Virtually none survive; most destroyed during damnatio memoriae

Near-Contemporary (75-150 CE)

Pliny the Elder (died 79 CE): Some references to Nero's reign Josephus (37-100 CE): Limited mentions Reliability: MODERATE - closer to events but still politically motivated

Later Roman Sources (100-220 CE)

Tacitus (Annals, c. 109 CE): Most sophisticated analysis

Bias: Anti-imperial, pro-senatorial

Reliability: MODERATE-HIGH for major events, LOW for personal details

Suetonius (Lives of Twelve Caesars, c. 121 CE): Focuses on scandalous anecdotes

Bias: Sensationalistic, court gossip

Reliability: LOW for personal details, MODERATE for basic chronology

Cassius Dio (c. 220 CE): Written 150+ years later

Reliability: LOW - heavily dependent on earlier hostile sources

Alternative Traditions

Bishop John of Nikiou (c. 680 CE): Coptic Egyptian chronicle

Distance: 600+ years after events

Cultural context: Christian, non-Roman perspective

Reliability: VERY LOW for specific details, but represents alternative tradition outside Roman control

Significance: Shows different stories circulated beyond Roman sphere

Modern Historical Assessment

Scholarly Consensus: Most sensational stories about Nero are propaganda Evidence of Manipulation:

Half of details in Suetonius contradict other sources

Many "prophecies" clearly written after events

Archaeological evidence contradicts some literary accounts

What Remains Credible:

Basic chronology of major events

Nero's artistic interests and public performances

Economic and military policies

Violent end to reign

What's Highly Dubious:

Specific personal anecdotes

Motivational explanations for actions

Details about family relationships

Circumstances of various deaths

The timeline reveals how thoroughly political interests shaped the historical record. While the specific theory about Nero's gender remains highly speculative, the systematic destruction of contemporary evidence and the survival of alternative accounts like John of Nikiou's demonstrate that our understanding of this period is built largely on politically motivated sources writing generations after the events they describe.

My Research, in Detail

The name Nero is synonymous with tyranny, but what do we really know about the infamous Roman emperor? After 2,000 years most people still recognise the name Nero, emperor of Rome. He is remembered as a monster and sadist with a chilling list of crimes to his name, from burning down his own capital city to sleeping with his mother and murdering many of his close relatives. Romans told very tall stories about their emperors in general, and the Emperors that came after him were known for undergoing a history wipe out, exaggerating his flaws where his name remained on official record.

Regarding the fire: One writer, not long after the event, describes how Nero watched the blaze from the outskirts of the city, singing to his lyre (though another claims he was actually 60 kilometres away at the time). But the singing doesn't mean that he didn't care. It is clear that after the disaster, he organised efficient relief operations, opening his own palaces for shelter and paying for emergency food supplies. And he introduced new fire regulations, insisting on a maximum height for buildings and the use of non-flammable materials. One graffito ran 'Romans escape, the whole city has become one man's house'. But there is no evidence at all that he torched the city in order to build the palace. Nero himself actually blamed the Christians, as a radical new sect, and had many of them horribly put to death (some burnt alive, others torn to pieces by animals).

Agrippina, the fourth wife of the emperor Claudius, was one of those powerful women in Rome who were probably blamed for many more crimes than they actually committed. But the whole story was wildly embellished, including a bizarre first attempt to stage an 'accident' in a specially constructed collapsible boat (which supposedly failed because, while the boat did collapse, Agrippina turned out to be a strong swimmer!)

Regarding the murders, there has always been a tendency to pin on Nero any sudden death that took place close to the centre of power, whether there is any evidence or not. Britannicus may just have been a victim of illness rather than poisoning. Who knows?

So, was he popular with anyone?

Yes. Outside the city of Rome, he went down well with the people of Greece (he granted them their 'freedom', which amounted to an enormous tax break). Inside the city itself, he most likely had support among the ordinary people. The problem here is that most of our evidence comes from the writing of the upper class, who had their own (snobbish and self-interested) ideas of how an emperor should behave and tended to think of generosity to the poor as buying popularity from the 'rabble'.

Nero sponsored public works, entertainments and shows and gave cash handouts, as well as having 'the common touch' with ordinary people. For years after he died, his tomb was decorated with flowers. Some people wanted to remember him.

This is one of my favorite, due to the connection with Africa. Why did Nero send an expedition into the continent of Africa?

This expedition is mentioned by several Roman writers who differ on the reasons for it. Some thought he was scouting for a possible invasion. Others imagined it was scientific exploration to discover the source of the river Nile. Nero's tutor Seneca (later one of Nero's victims) put it down to the emperor's 'love of truth'. It was probably a bit of both, but it started a European imperialist fascination with the river's source that lasted into the 19th century. This helps us see that Egypt did not dissappear yet, not in significance or interest. The fact that it was illegal for emperors to visit Egypt except under strict vote shows they still had power.

It is also interesting to read that Nero liked to walk among the people, showing more of an interest than Romans would like to think of their elite. Mostly performing on stage, but he is also said to have enjoyed exploring the city's night-life incognito – as later royals have done, right down to the present British royal family. It was, of course, turned against him, especially when he got involved in drunken brawls. After one nasty confrontation, he apparently decided that it was wiser to take an armed guard with him.

How did Nero die? It was an almost poignant end in AD 68. The armies had turned against him and he was deserted by the senior palace officials. Only his slaves and ex-slaves stayed loyal, helping him to take his own life, and taking his body away for burial. By lucky chance the original tombstones of two of these people have been found – Epaphroditus who guided the hands of Nero with the dagger, and Ecloge, his old nurse who buried him. They are a precious link with the real people around the emperor, beyond myth and hype.

But did he really die in AD 68? Some Romans thought not. Uncannily, like Elvis Presley, claims soon surfaced that he was still alive somewhere. In fact, over the next couple of decades, at least three 'false Neros' appeared to take back the throne. This is another hint at his popularity with some, for surely no-one would seek power by claiming to be an emperor that everyone detested.

Most of the stories and 'facts' referred to here come from Suetonius, Life of Nero and Tacitus, Annals (a history of Rome between AD 14 and 68), both written in the early second century AD. You can find translations of both online.

The writer: John of Nikiû, (680–690 AD) was an Egyptian Coptic bishop of Nikiû (Pashati) in the Nile Delta and general administrator of the monasteries of Upper Egypt in 696. He wrote a general history of time from Adam to the Islamic conquest of Egypt in the 600’s. Two originally independent biographies mention John. The Patriarch Simeon removed John from office for having disciplined a monk (presumed guilty of leading other monks into removing a nun from her monastery's cell in Wadi Habib and sleeping with her) so severely that the monk died ten days later.

The original editor of this text, Zotenberg, argued that John of Nikiû's Chronicle was originally written mostly in Greek, theorising that some of the name forms indicate that John wrote the sections concerning Egypt in Coptic. Scholarly opinion has shifted, however, to the belief that this chronicle was probably written in Coptic.[2] The work survives only in a Ge'ez translation.[3] In 1602, an Arabic translation of the original was made. Sections of the text are obviously corrupted with accidental omissions. Most notably, a passage covering thirty years (from 610 to 640) is missing. The narrative, especially the earlier sections up until the reign of Constantine, has many obvious historical errors. These may be due to mistakes by the copyist, or to a policy of deliberate negligence towards Pagan history. There are also many instances of myth and less a reliance on pure history, for instance, Julius Caesar's mother being cut open to birth him, resulting in a Caesarian section. This is a fable made up by later historians and bears no evidence to historical fact.

I still wonder, who would WANT to say he was a woman??? John's view of the earliest periods of history is informed by sources such as Sextus Julius Africanus and John Malalas.

Perhaps the most important section of John's Chronicle is that which deals with the invasion and conquest of Egypt by the Muslim armies of Amr ibn al-Aas. Though probably not an eyewitness, John was most likely of the generation immediately following the conquest, and the Chronicle provides the only near-contemporary account. Nero would have been about 600 years before his time! That is like me writing about the year 1400, and before the internet or even the printing press!

Could Nero have been a woman?

There is actually another person in Roman history who was thought to have been a man, until she became pregnant, and controversy ensued. She was actually a Pope, and known as Pope Joan.

I am writing a story on the history of Egypt, and how it is relevant to us, and there is a 1,000 years of the “Dark Ages” in European History where Arab works shed light on our own lineage in America an beyond. Most important to recognize is the widespread use of “Damnacio Memoria” in Roman Times, or the idea of striking a person from history if they were no longer in favor. Nero is one of those Emperors that is widley hated, and did, in fact, get this treatment. It would not be so surprising to see that there is a chance he was actually a she!!

More on Nero, the more common version:

He is thought to be a person who may have started a fire that destoryed his city, yet laughed as it burned. It is said that he killed his pregnant wife out of anger. But then, history books quickly say not to beleive all of that as fact, as the history around him is quite suspect, and known to be manipulated. Given the Arab version of a story, this should definately make us take pause and consider re-evaluating.

His mother’s story

Julia Agrippina lived from 15 AD to 59 AD, the same time as Jesus would have lived. She was a roman empress in her own right for 5 years, and the 4th wife of Claudius. She had some very royal blood: niece of her husband, but also related to Augustus and Julius Caesar (through her mother).

This was a little confusing, but here is what it says:

Agrippina the Elder was related to Julius Caesar through her mother, Julia, who was the only biological child of Augustus (who adopted Caesar's name). Agrippina was Augustus's granddaughter, and because Augustus was Caesar's adopted son (and nephew), this made Agrippina a descendant of Caesar.

I had to ask some more questions to clarify: So the Agrippinas (mother and daughter) were directly blood-related to Julius Caesar. Their shared familial ties came through Caesar's great-nephew and adopted son, Augustus. Augustus was blood-related to Julius Caesar; he was Caesar's great-nephew, the son of Caesar's sister's daughter, Atia. Caesar formally adopted Augustus as his son and heir in his will after his death.

So yes, she was Julius’s great great niece. Julius Caesar's sister, Julia, was the grandmother of Augustus. This made Augustus Caesar's great-nephew by blood. Agrippina the Elder was the daughter of Julia the Elder, making her Augustus's granddaughter and Julius Caesar's great-great-niece.

So anyways, she had some royal heritage, and was one of the most prominent women in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Agrippina's brother Caligula became emperor in AD 37, assassinated 4 years later. That is when Claudius took the throne and married Agrippina in 49 AD. Agrippina has been described by modern and ancient sources as ruthless, ambitious, domineering and using her powerful political ties to influence the affairs of the Roman state, even managing to successfully maneuver her son Nero into the line of succession. (this is where I get interested… could sh e have maneuvered a woman into the throne??)

Claudius eventually became aware of her “plotting” (to what, make her son emperor?? or would this imply more sinister for the times…), (this is as mentioned in Wiki), but died in AD 54 under suspicious circumstances, potentially poisoned by Agrippina herself. She held significant political influence in the early years of her child's reign, but eventually fell out of favor with him and was killed in 59 AD.

Wiki then says somehting confusing to me, so I had to ask about it: “Agrippina's two eldest brothers and her mother were victims of the intrigues of the Praetorian Prefect Lucius Aelius Sejanus.”

The phrase means that Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the commander of the Praetorian Guard, used his influence through manipulative schemes ("intrigues") to arrange the deaths of Agrippina the Elder's two oldest sons (who were also the emperor Tiberius's likely heirs) and later her. This would have been part of the all too familiar Roman scheming of eliminating potential rivals of anyone associated with the Emperor, even, and especially, family.

Germanicus, Agrippina's father, was a very popular general and politician. In the year AD 9, Augustus ordered Tiberius to adopt Germanicus, who happened to be Tiberius's nephew, as his son and heir. Germanicus was a favourite of Augustus, who hoped that he would succeed Tiberius, who was Augustus's adopted son and heir and then emperor following Augustus' death in AD 14.

Aggripina (the Younger, the one we care about, the mother of Nero), was born in 15 AD, most likely at a Roman outpost in Germany along the Rhine River, but the place and year is debated. A different author says she was born in the city of Trier in what was Caul, but along another river Moselle in Germany.

As a small child, Agrippina travelled with her parents throughout Germany until she and her siblings (apart from Caligula) returned to Rome to live with and be raised by their paternal grandmother Antonia. Her parents departed for Syria in AD 18 to conduct official duties. Another sister was born en route to Lesbos. In AD 19, Germanicus died suddenly in Antioch (Turkey). Germanicus' death caused much public grief in Rome, and gave rise to rumours that he had been murdered on the orders of Tiberius (Who ordered his adoption). Agrippina then grew up on the Palatine Hill in Rome with her mother, grandmother, and great Grandmother.

After her thirteenth birthday in AD 28, Tiberius arranged for Agrippina to marry her paternal first cousin, Domitius. Not much is known of their relationship. Tiberius really seems to have had a hand in everything in her life.

Tiberius died in AD 37, and Agrippina's only surviving brother, Caligula, became the new emperor. Being the emperor's sister gave Agrippina some influence. Agrippina and her younger sisters (two different Julia’s). They received the rights of the Vestal Virgins (without having to become one), such as the freedom to view public games from the upper seats in the stadium; were depicted on coins, opposite to their brother; and they were mentioned in oaths as "I will not value my life or that of my children more highly than I do the safety of the Emperor and his sisters".

Around the time that Tiberius died, Agrippina had become pregnant. Domitius (her husband) acknowledged the paternity of the child. In AD 37, in the early morning, in Antium, Agrippina gave birth to a son. Agrippina and Domitius named their son Lucius, after Domitius' recently deceased father. This child would grow up to become the emperor Nero. Nero was Agrippina's only natural child. Suetonius states that Domitius was congratulated by friends on the birth of his son, whereupon he replied "I don't think anything produced by me and Agrippina could possibly be good for the state or the people".

What could that possibly mean??

I asked Google, and it said: this quote reflects the dangerous political climate of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the notorious reputations of both parents. The quote, documented by the Roman historian Suetonius, suggests that Domitius believed a child born of their union was destined for evil and would harm the state.

I don’t know anyone thinks their child was destined for evil. Already, this has the marks of propoganda all over it. These kinds of “prophecies” were often added to “histories” after the fact, to help predict the future, and pretend it was already destined.

Looking into Suetonius and what he thought of the father: According to Suetonius, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus was a "detestable" man with a reputation for brutality and cruelty. He was accused of crimes of murder and cheating the public. Even though Wiki’s article on Agrippina the Younger says she was a model of an upper class Roman Woman, this section calls her the sister of the emperor Caligula, a man infamous for his tyranny and incestuous relationships. Given her own ruthless ambition for power, her family connections were a source of danger rather than security.

The family's legacy of infamy and hunger for power, he supposedly “predicted”, would poison anyone born into it.

The son born to them, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, would become the emperor Nero, whose reign became a byword for matricide, political tyranny, and ruin. The dark family legacy, combined with Agrippina's manipulative quest for power, turned their son into one of Rome's most reviled rulers.

Caligula and his sisters were accused of having incestuous relationships. But they were also all marrying eachother, sooo… was that really a problem?

In AD 38, Drusilla died, possibly of a fever, rampant in Rome at the time. Caligula was particularly fond of Drusilla, claiming to treat her as he would his own wife, even though Drusilla had a husband. Following her death, Caligula showed no special love or respect toward the surviving sisters and was said to have gone insane. Apparently, a year later, Agrippina, Livilla, and their maternal cousin Lepidus were said to be involved in a failed plot to murder Caligula, known as the Plot of the Three Daggers. They were also all accused of being lovers. “Not much is known concerning this plot and the reasons behind it”, though.

At the trial of Lepidus, Caligula produced handwritten letters discussing how they were going to kill him. The three were found guilty as accessories to the crime. (Accessories?) And also known as adulteresses. All of them, like, with each other.

Lepidus was executed. Agrippina and Livilla were exiled by their brother to the Ponza Islands, about 70 miles away from Rome.

Caligula sold their furniture, jewelery, and slaves. In AD 40, Domitius died of edema, a strange skin illness. Their child, Lucius had gone to live with a paternal aunt after Caligula had taken his inheritance away from him.

Caligula, his wife, and daughter, where then all murdered in AD 41. Agrippina's paternal uncle, Claudius, brother of her father, became the new Roman emperor. Claudius allowed Agrippina and her sister to return out of exile, and she was reunited with her child that same year. Livilla was executed a few years later, for a supposed relationship with Seneca, a famous statesman.

Apparently, Agrippina tried to make shameless advances on the future emperor Galba, but he showed no interest. Anyways, Lucius was allowed to have his inheritance reinstated, and he became more wealthy as other aunts and uncles died or remarried. Agrippa remarried some rich guy, Crispus, but little is known about their relationship, and he soon died (AD 47) and left his estate to her son, Nero/Lucius.

Agrippina was very influential at this time, and she apparently kept a low profile and stayed away from the imperial palace. (Interesting as this would have been the time her child was growing up, possibly showing not a man???). Her sister was killed at this point by the first wife of the man she would soon marry.

Then there is a plot to kill her son, (Nero), full of serpents and omens: Messalina considered Agrippina's son a threat to her son's position and sent assassins to strangle Lucius during his sleep. The assassins left after they saw a snake beneath Lucius' pillow, considering it a bad omen. It was, however, only a sloughed-off snake-skin. By Agrippina's order, the serpent's skin was enclosed in a bracelet that the young Lucius wore on his right arm. (like, the whole thing?? how long was this bracelet for a newborn??)

At Crispus’ funeral, a rumour spread that Agrippina had poisoned Crispus to gain his estate. She was left very wealthy, and with no husband, again. Romans really would not have liked her. But apparently, at some later event, Agrippina and her child received greater applause than the Emperor’s wife, Messalina, and she really did not like that.

Messalina was executed in AD 48 for conspiring to overthrow her husband. (Who really knows though…). Around this time, Agrippina became the mistress to one of Claudius' advisers. But Claudius also had just ended his marriage (by executing her) and was looking for a new noblewoman to marry. It has been suggested that the Senate may have pushed for the marriage between Agrippina and Claudius to end the feud between the Julian and Claudian families. (So the Senate was plotting royal marriages??). This feud dated back to Agrippina's mother's actions against Tiberius after her husband died. (always a woman’s fault). But it would have also put her child up for succession, who had all kinds of royal blood.

When Claudius decided to marry her, he persuaded a group of senators that the marriage should be arranged in the public interest. In Roman society, an uncle (Claudius) marrying his niece (Agrippina) was considered incestuous and immoral. But in 49 AD, they did it anyway, with widespread disapproval.

Here it is funny, someone on Wiki writes: “was not based on love, but power – possibly being a part of her plan to make her son Lucius the new emperor.” (Sounds like the Senate’s too!)

At this point, Agrippina ends up on a coin again, but just her face, oppositte to her husbands, and with no ambiguity. She became stepmother to one of her husband’s daughters (from his second wife, though he had 2 more children with Messalina who were not adopted). Apparently Agrippina removed or eliminated anyone from the palace who seemed to have favored his ex wife, Messalina, as well as anyone she saw as a potential threat to her child. (There is a huge chance here there is some truth, that maybe she did not want anyone spending too much time around her child, who was possibly a woman).

Griffin describes how Agrippina "had achieved this dominant position for her child by a web of political alliances," which included a chief secretary and bookkeeper, his doctor, and the head of the Praetorian Guard (the imperial bodyguard), who owed his promotion to her.

In parades, she was bowed to by some (even Celtic Kings) in the same way they bowed to the Emperor (which must be a big deal if had to be noted). In AD 50, Agrippina was granted the honorific title of Augusta. She was the third Roman woman to receive this title. In the 200’s it was synonymous with Mater Patriae (Mother of the Fatherland).

Agrippina quickly became a trusted advisor to Claudius, and by AD 54, she exerted a considerable influence over the decisions of the emperor. Statues of her were erected in many cities, and her face appeared on coins. In the Senate, her followers were advanced with public offices and governorships ( I guess meaning she had some kind of influence on their voting). According to Cassius Dio, Agrippina was often present with Claudius in public, seated on her own platform as a "partner in the empire". This seemed to have caused some resentment in rich families.

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was adopted by his great maternal uncle and stepfather in AD 50. Lucius' name was changed to Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus and he became Claudius's adopted son, heir and recognized successor. Agrippina and Claudius betrothed Nero to his step sister Claudia Octavia, and Agrippina arranged to have Seneca the Younger return from exile (the one her sister was murdered for) to tutor the future emperor.

Claudius founded a Roman colony named after her: Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensis, sometimes just called Agrippinensium, today known as Cologne, after Agrippina who was born there. This was the only Roman colony to be named after a Roman woman. In AD 51, she was given a carpentum: a ceremonial carriage usually reserved for priests such as the Vestal Virgins and sacred statues.

Nero and Octavia were married AD 53. So the daughter of her husband was married to her son. But his other son, his real son, was further separated from his father. In AD 51, Agrippina ordered the execution of Britannicus' tutor Sosibius. Sosibus had confronted her, outraged by Claudius' adoption of Nero and his choice of Nero as successor over his own son Britannicus.

Claudius died in 54 AD, and accounts vary widely over the cause. This seems to have been a private incident, and more modern sources say it is possible that he died of natural causes, being 63 years old. But the more popular roman tale was that Agrippa killed him with a plate of deadly mushrooms at a banquet.

There are claims that Claudius later regretted adopting Nero and began to favor his own son Britannicus (born 41 AD), giving Agrippina a motive to allegedly eliminate her husband, so that her child, Nero could quickly take the throne as emperor. In the aftermath of Claudius's death, Agrippina, who initially kept the death secret, tried to consolidate power by immediately ordering that the palace and the capital be sealed. After all the gates were blockaded and exit of the capital forbidden, she introduced Nero first to the soldiers and then to the senators as emperor. Most likely to make sure the soldiers would protect him.

Nero was raised to emperor and Agrippina was named a priestess of the new religion of her deified husband. It was an Egyptian custom to make the Queens and Kings reincarnated Gods, something that allowed Augustus to take the throne- since it upset the Romans to see one of their Emperors as a God. They got around it by deifying after death, but some even while living. This shows how politics- not real religion, was behind who gets turned into a God or Not.

It seems it may not be so hard to believe her son could have been a daughter. The child would have been only 16 years old when taking the throne (born 37 AD). Thanks to the thinking of his mother, his succession that was smooth due to support from the army and the Senate.

His-story says Nero had Britannicus secretly poisoned during his own banquet in February AD 55. In AD 56, Agrippina was forced out of the palace by her son to live in the imperial residence. However, Agrippina retained some degree of influence over her son for several more years, and they are considered the best years of Nero's reign. Nero even threatened his mother that he would abdicate the throne and would go to live on the Greek Island of Rhodes (Turkey), a place where Tiberius had lived after divorced.

The circumstances that surround Agrippina's death in 59 AD are uncertain due to historical contradictions and anti-Nero bias. (ie. nothing about Nero’s life can be certain!!) However, the ancient accounts seem to agree that Nero somehow murdered her.

Some say he murdered his mother because he fell in love with a woman his mother dissapproved of, but he did not ask for divorce until 3 years later, calling into question this theory. Historians theorise that Nero's decision to kill Agrippina was prompted by her plot to replace him with his own cousin or half brother. (But how would that give her any control over her own child? Seems like an odd choice for a power hungry woman to me.)

Nero then told the Senate that Agrippina had plotted to kill him and committed suicide.

Whatever the sinking boat story, Agrippina seemed to have been a survivor, and was met at the shore by crowds of admirers. The Roman historians must not liked to have admitted how much people liked her. Apparently he also tried to poison her, three different times, but she prevented her death by taking the antidote in advance.

But everyone’s account is a bit different.

At his mother's funeral, Nero was witless, speechless and rather scared. He would later have nightmares about her. Years before she died, Agrippina was said to have visited astrologers to ask about her son's future. The astrologers had rather accurately predicted that her son would become emperor and would kill her. She replied, "Let him kill me, provided he becomes emperor," according to Tacitus.

Her household later on gave her a modest tomb in Misenum. (notice the Iss sound? Near Naples, an EtrUScan port)

Agrippina left memoirs of her life and the misfortunes of her family, which Tacitus used when writing his Annals, but they have not survived. Scholars interpret the existence of her memoirs as evidence of Agrippina’s political self-awareness and her attempt to shape her historical legacy—an unusual endeavor for a Roman woman of her time.

Most ancient Roman sources are quite critical of Agrippina the Younger. Tacitus considered her vicious and had a strong disposition against her. But in her summary in Wiki, she was one of the most prominent women in her dynasty, and a beauty. Pliney the Elder even described her looks as signs of good fortune in Ancient Rome, including a double canine in her upper right jaw. Agrippina was described as a beautiful and reputable woman. But by who, when all the Romans were saying awful things, makes us wonder what history books we are not reading to get that information.

How much of nero's story that survives is fact?

Historians caution that much of the surviving story of Emperor Nero is based on propaganda and biased accounts, making it difficult to separate fact from exaggeration and outright fabrication. Most of the primary sources were written by elite Roman senators or upper-class authors who were hostile to Nero and wrote their histories after his death. These biased sources have overshadowed the historical reality that Nero was popular with the lower classes for much of his reign.

A devastating fire destroyed large parts of Rome in A.D. 64. While Nero was not in the city when it began, he did organize relief efforts for the victims. Many teachings like to say Nero may have set the fire and even smiled as it burned. Following the fire, Nero built an extravagant new palace, the Domus Aurea (Golden House), on the cleared land. In this narrative, In an effort to deflect blame for the fire, Nero scapegoated and harshly persecuted Christians (revealing as to who would want to have this opinion embedded in history). After losing the support of the Praetorian Guard amid several revolts, Nero fled Rome and committed suicide in A.D. 68.

Why do we think much of his story was fabricated? we know there was damnacio memorie. But also, some like the legend of Nero playing a fiddle during the Great Fire are known to be completely false. The fiddle didn't exist in ancient Rome, and Nero was not in the city at the time. The rumor was likely created by political opponents to portray him as detached and cruel.

While Nero took advantage of the cleared land to build his palace, the accusation that he started the fire deliberately is likely propaganda from hostile sources like Suetonius.

Stories of Nero's sexual and depraved acts were often exaggerated by sources like Suetonius to discredit him. In many cases, these scandalous tales share similarities with established Roman literary techniques, rather than being factual accounts.

Some details of Nero's crimes were likely embellished for dramatic effect. One historian's account of Nero poisoning his step-brother, Britannicus, contains details about the poison that were not scientifically possible at the time. (when were these available, helping us to know when the story may have been manipulated?)

While Nero's obsession with music and acting was factual, ancient historians presented this as a sign of his degeneracy because such public performances were considered below the dignity of the Roman elite. The common people, however, enjoyed these spectacles.

Because all the major surviving Roman historians—Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio—wrote decades after Nero's death under different ruling dynasties, their accounts are highly suspect. Their anti-Nero bias was motivated by several factors:

Political agenda: Denigrating Nero helped legitimize the subsequent Flavian and other ruling dynasties.

Class animosity: As aristocratic senators, they resented Nero's disdain for their authority and his focus on populist reforms and public entertainment.

Historical convention: Ancient historians often reported rumors alongside facts, allowing readers to draw their own (often negative) conclusions.

Yes, Nero suffered a damnatio memoriae after his death in 68 AD. The Flavian emperors who followed him ordered the destruction of his public images, the erasure of his name from inscriptions, and the destruction of many of his coins, though the practice wasn't completely successful as evidence of his reign still exists today.

Damnatio memoriae is a modern Latin term for the ancient Roman practice of condemning and symbolically erasing a person from public memory.

The punishment involved systematically destroying or altering a person's images and names on public monuments, inscriptions, and coins.

The goal was to remove the condemned individual's legacy from history and prevent them from having a lasting presence.

Nero's damnatio memoriae

Following Nero's suicide in 68 CE, the Flavian dynasty took power and implemented a damnatio memoriae against him.

This was done to erase his negative memory, though it also involved purging good memories of his popular economic reforms.

Despite the systematic efforts to erase him, Nero's memory has continued to be contested and discussed throughout history, largely due to the survival of literary evidence and later attempts to rehabilitate his legacy.

Damnatio Memoriae: On Facing, Not Forgetting, Our Past

the practice of desecrating and destroying public monuments is one with a long history, extending back specifically to the Roman world and its practice of damnatio memoriae.

While the phrase damnatio memoriae—a “condemnation of memory” in Latin—is modern in origin, it captures a broad range of actions posthumously taken by the Romans against former leaders and their reputations. Most prevalent during the Republican and Imperial periods, this tactic generally involved the defacement of all visual depictions and literary records of a condemned individual. This could come in the form of an official decree by an emperor or the senate, or a set of actions taken by the populace—a collective act of expression by the people against an unpopular leader. The literary and archeological records show that instances of damnatio memoriae weren’t decreed with much restraint. In fact, around half of all Roman emperors received some form of the condemnation, and from Caligula in 41 CE to Magnus Maximus in 388 CE, not many could escape its wrath.

When many people think of the Roman world, statues are often among the first artifacts that come to mind. Invocations and celebrations of leaders, gods, and events, these depictions were the bread and butter of any city in the empire. Statues of Roman emperors peppered many central public spaces, serving as symbols of the state’s power. At Roman funerals, relatives of the dead invoked images of the past, donning wax face masks of their ancestors to educate future generations about their heritage. In Roman religious life, many statues and visual representations held apotropaic roles, warding away harm from those they protected.

Surrounded by these statues and images, the average Roman constantly came into contact with the faces of these omnipresent gods, leaders, and heroes, both mythical and real. Many statues served multiple purposes at once; A statue of Augustus in a forum on the fringes of the empire was both state sponsored propaganda and a corporeal invocation of the emperor.

Given the proximity of these monuments to Roman life and the intertwined relationship between the two, it isn’t difficult to understand the visceral reactions many expressed toward these statues when a damnatio memoriae was declared against an individual. Pliny describes such a scene in his Panegyrici Latini, discussing the damnatio memoriae against the emperor Domitian following his assassination:

It was our delight to dash those proud faces to the ground, to smite them with the sword and savage them with [axes, as] if blood and agony could follow from every blow. Our transports of joy—so long deferred—were unrestrained; all sought a form of vengeance in beholding those bodies mutilated, limbs hacked in pieces, and finally that baleful, fearsome visage cast into fire, to be melted down, so that from such menacing terror something for man’s use and enjoyment should rise out of the flames (52.4-5).

For Romans like the ones whom Pliny describes, seeking and receiving the opportunity to not only watch the former emperor’s likeness topple to the ground, but also play a part in the toppling, provided them with a sense of restored justice. When reading his words, the agony of these individuals, who lost their relatives and friends to Domitian’s reign of terror, is tangible; It most likely gave them a remarkable sense of solace, and perhaps even fulfilled a wish for vengeance against the emperor.

Beyond literature, one surviving example that provides clear visual evidence of a damnatio memoriae is the painting of the Severan family on the Severan Tondo, now in the Altes Museum in Berlin. Before his death, the Roman emperor Septimius Severus appointed his two sons, Caracalla and Geta, to rule as co-emperors. However, as so often happens between siblings in Roman history (see: Romulus and Remus), Geta was assassinated by Caracalla, who ascended as the sole Caesar of the Roman state. Assuming his new role, Caracalla declared a damnatio memoriae against his late brother, even threatening execution to those who spoke Geta’s name. Today, the tondo clearly portrays Septimius Severus, his wife, and his son, Caracalla, as a smiling family, while Geta’s face has been not-so-subtly scraped from the portrait.

A second example, one closer to home, can be found within our own Penn Museum and references the damnatio memoriae declared against Domitian. The Puteoli Marble Block contains an inscription on one side, which once spoke in praise of the emperor. However, as Pliny above, as well as Suetonius, describe, following Domitian’s death in 96 CE, the senate, embittered by Domitian’s authoritarian rule and paranoid nature, passed a decree against him; chiseling his name off all inscriptions and removing the heads from his public statues, they worked to erase his face and image from the empire. Nevertheless, the attempted erasure of the Puteoli Marble Block’s inscription wasn’t entirely successful, as one can still make out some of its words. Additionally, despite the efforts to remove his face and name from the legacy of Rome, Domitian still lives on in history as one of the most famous Roman emperors, and even today, his name recalls paranoia and abuse of power.

These unsuccessful and conspicuous “erasures” beg the question: was a damnatio memoriae truly intended to fully erase the memory of these individuals and their actions, condemning their legacies to obscurity, as its name suggests? That is certainly the view of Sarah Bond, who believes the destruction of the memory of a former emperor allowed for easier transition between rulers, serving a “cathartic purpose.” However, the apparency of these vandalisms betrays another intention. Lauren Hackworth Peterson, a professor at the University of Delaware, counters Bond, proposing that damnatio memoriae had the opposite effect on communal memory. In destroying images of their emperors through public actions, she argues, the Romans in fact created a void which “call[ed] attention to itself;” these manufactured absences became monuments to both the removed statue and the events that led to its removal. According to Peterson, when a damnatio memoriae was enacted, the victim’s memory was not forgotten, but rather condemned. As classicists, this is quite clear—one can hardly say that history has forgotten Nero, Caligula and Domitian. Instead, we remember them almost exclusively for their negative attributes and decisions: the things that they did wrong. Their legacies shed light upon the nature and purpose of a damnatio memoriae—it served to reset the political landscape, not by drowning the people’s consciousness in Lethe’s stream, but instead by reshaping the narrative of the past.

Here, it’s crucial to mention that as we draw comparisons between current and ancient events and institutions, we cannot pretend that the ancient world is the same as our own. Nearly two thousand years after the infamous reign of Domitian, public statues no longer serve the same educational functions as they did then, since modern technologies and nationwide schooling have risen to fill those roles.

Still, the legacy of damnatio memoriae has extended far beyond the Romans, having become a fixture of politics and society across nations and cultures. Several years ago, Ukraine removed all statues of Lenin from the country in an effort to move on from its Soviet past. And although calls for statue removals have made national headlines in recent weeks, months, and years, the practice of damnatio memoriae in the United States has appeared throughout many pivotal moments in our nation’s history, particularly during the American revolution.

Rome’s Dislike of his Mother

Rome likes to say his mother was too involved in the beginning, but also, as seen below, he is seen as being a good ruler, at least in the beginning. But instead of crediting his mother, historians credit men, like Seneca and Burrus.

Nero's early reign, guided by the philosopher Seneca and the prefect Burrus, was considered a period of "good government" and a "golden age" for Rome. During this time, he was involved in diplomacy, trade, culture, and the popularization of athletic and artistic competitions.

Nero was a notorious Roman emperor and the last of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, known for his cruelty, extravagance, and alleged involvement in the Great Fire of Rome. Born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in 37 AD, his mother, Agrippina, orchestrated his adoption by her husband, Emperor Claudius, and his subsequent rise to power in 54 AD at age 16. Early in his reign, he received good advice from Seneca and Burrus and was considered an effective ruler, but he eventually became tyrannical, orchestrating his mother's death, his wife Octavia's execution, and engaging in a life of debauchery. He ruled until his death in 68 AD, with the last years of his life marked by rebellion and a desperate attempt to maintain control.

Nero grew increasingly dependent on his own desires, leading to a power struggle with his mother. It is when he was fighting with his mother (supposedly) that also his ruling seemed to suffer, not because of her, but because of himself.

He had his mother executed in 59 AD, divorced his wife Octavia (who was later executed), and married his mistress, Poppaea.

His infamy grew due to his alleged role in the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, a period during which he also allegedly persecuted Christians.

His death marked the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and led to the tumultuous Year of the Four Emperors.