Gold and Haram: How Two Words Tell the Story of Women’s Power and Its Loss

Sometimes, history hides in a single syllable.

One word glitters with divine light. Another darkens into walls and silence. Together, they tell the story of how women’s power has been remembered—and how it has been erased.

Gold: The Eternal Light

In ancient Egypt, gold was not just a metal. It was the flesh of the gods—indestructible, eternal, radiant as the sun.

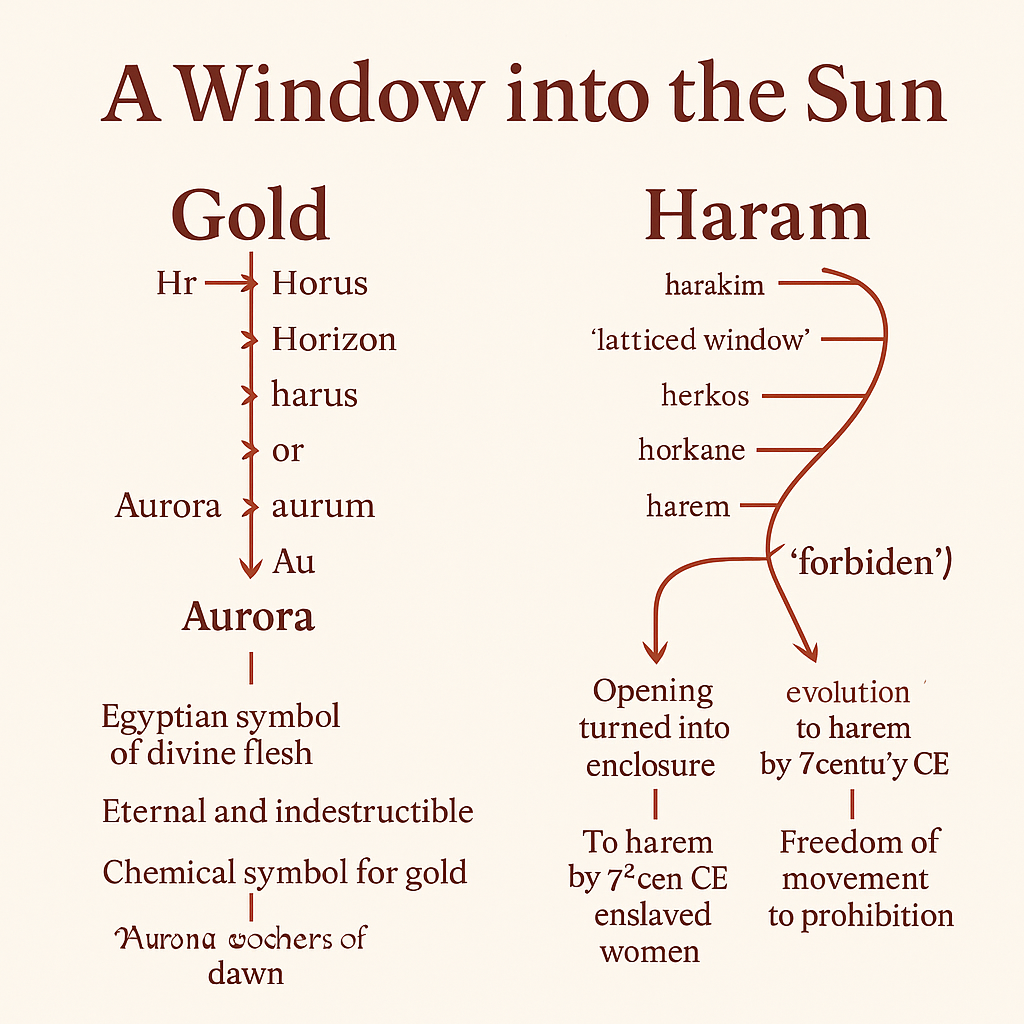

The roots of the word itself preserve this radiance:

Hr / Hrw → Horus, the falcon-headed god of light.

Horus → horizon → the place where his eye met the dawn.

Harus → hurasu → oro → aurum → gold in Canaanite, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Spanish, French.

Aurora → Roman goddess of dawn.

Au → still the chemical symbol for gold today.

The connection is unbroken. From 4th millennium BC Egyptian amulets to the coins in our pockets, the word for gold has carried the same meaning: divinity, light, immortality.

Egypt’s wealth came from its gold mines, yes. But the deeper wealth was linguistic. Every time we say oro, aurum, Aurora, or even see the letters Au, we’re speaking fragments of Egypt’s sacred science of light.

Gold, as a word, is continuity. It is memory preserved.

Haram: From Window to Wall

Now consider a very different word: haram.

It begins innocently enough in ancient Semitic tongues:

harakim → a latticed window, a woman looking outward.

herkos (Greek) → an enclosure, a fence.

horkane → a prison.

haram / harem → “forbidden,” “sacred,” or “women’s quarters.”

The transformation is stark. What began as an opening—a window—slowly became a barrier. A threshold became a cage.

By the 7th century CE, during the Muslim conquests (622–750), the word had hardened. With sudden influxes of enslaved women—sometimes thousands per elite household—the harem became an institution of confinement. Eunuchs guarded the gates. Curtains sealed the rooms. Women became “forbidden” not because of holiness, but because of possession.

Poetry from the Abbasid period speaks the horror: fathers describing the death of a daughter as a blessing—better to lose her to God than to see her enslaved.

And yet, even within the walls, women’s voices refused silence.

Raabi’a al-Adwiyya, a Sufi mystic, sang of divine love.

‘Ulayya bint al-Mahdi, a princess-poet, left verses of piercing clarity.

Courtesans like Shāriyah and Arib al-Ma’muniyya wrote songs still remembered.

But the pattern was set: what had once been freedom of movement became prohibition; what had once been voice became enclosure.

Unlike gold, haram is a word of rupture. It remembers not radiance but restriction, the systematic narrowing of women’s power.

Two Words, Two Histories

Gold carries the story of light preserved: Horus to Aurora, horizon to Au. A word that shines across millennia.

Haram carries the story of light suppressed: a window turned into a wall, a woman turned into “the forbidden.”

One word remembers continuity; the other encodes loss.

Both remind us that language is more than grammar. It is the DNA of culture, carrying forward the choices societies made—whether to honor women’s power, or to confine it.

Why This Matters Now

Every time we admire gold, we are touching Egypt’s gift: a story of light that was never fully extinguished.

Every time we hear haram used casually, we are brushing against centuries of erasure, confinement, and fear of the feminine.

The lesson? Words are not neutral. They carry memory. They preserve both the brilliance and the betrayals of our ancestors.

And by uncovering those memories, we have a choice.

Do we continue repeating the old cages, or do we return to the older gold—where light was divine, where women were honored as radiant, and where language itself was a window, not a wall?