The Name "King"

These sources examine naming traditions, particularly the prevalence of royal and honorific names like "King" and "Queen" in African American culture. They discuss how these names reflect cultural identity, pride, and a connection to African heritage, especially during the Black Power movement, and explore possible ancient linguistic and symbolic connections across different cultures, including Egyptian, Near Eastern, and European goddess names and feminine linguistic markers, suggesting an enduring association between certain sounds, nationality, wisdom, and power. The texts also touch on African female leadership and the underacknowledged African foundations of aspects of Western civilization, like the alphabet and Christianity, arguing that recognizing these contributions helps to reframe historical narratives and foster greater understanding and dignity.

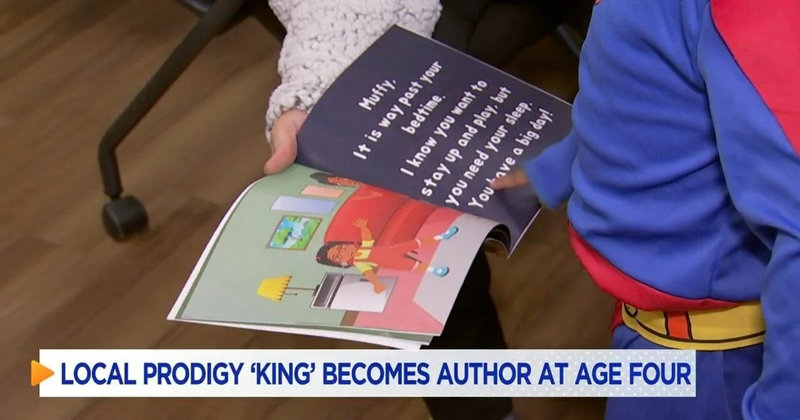

As I looked for an image for this idea, I found an example of the cutest little boy named King who wrote a book at 4 years old, and it’s adorable. And of course, he is African American. There is something about this name that feels particularly African. Why is that?

African naming traditions include names that reference royalty or nobility, though they vary by region, language, and cultural context.

In several African cultures and languages, there are names that directly relate to concepts of royalty, leadership, and divine power:

In Akan (Ghana):

Oba (king)

Ohemaa (queen)

Afia Odo (royal one)

In Yoruba (Nigeria):

Adé (crown, royalty)

Ọba (king)

Ayaba (queen)

In Swahili:

Mfalme (king)

Malkia (queen)

In various Bantu languages:

Simba (lion, often associated with kingship)

Malik/Malika (king/queen, though this has Arabic origins)

In Egypt:

The sun gods Ra and Amun appear each appear almost 100x in pharaoh’s names

The ancient Egyptian Ra/Re sound appears in words related to royalty, divinity, and power across multiple languages and cultures

English/American names use names like "King" and "Prince", though rare, and only usually seen in people of African backgrounds. Some more modern examples of royal honorary names in African American culture can be seen as a continuation or reclamation of African naming traditions.

Some examples include:

King (used as both first and middle name)

Queen (as in Queen Latifah)

Prince

Princess

Royalty

Royal

Majesty

Duke

Earl (though this has Anglo origins too)

Queenie

Empress

Reign

This naming pattern became particularly notable during the 1960s-70s with the rise of Black Pride and Black Power movements, when many African Americans sought to reclaim cultural identity through naming practices.

This naming pattern holds parallel with "Christ" in personal names. Many various “krist’s” existed before JC. The incorporation of divine or royal elements in names does show how cultural patterns move across civilizations. The example of "Mary" (from Egyptian "mry" meaning beloved) demonstrates this cultural transmission from Africa to Europe and beyond.

These naming patterns reflect a powerful cultural practice - using names as affirmations of identity, dignity, and aspiration. The continuation of royal naming in African American culture can be seen as maintaining a connection to African heritage while creating new expressions of cultural identity in the American context.

The Rise of Royal Names in the Black Power Era

During the 1960s and early 1970s, America witnessed a profound shift in African American naming practices. As the Black Power movement gained momentum, many African Americans deliberately chose names that reflected dignity, power, and self-determination.

This wasn't simply a matter of style. It was a revolutionary act of reclaiming identity.

Names like King, Queen, Prince, Royal, and Majesty became increasingly common in African American communities. These weren't just random choices but deliberate statements that challenged centuries of forced anonymity and the erasure of heritage that began during slavery.

Historical data confirms this wasn't just anecdotal. Research by economists Cook, Logan, and Parman found that even in the early 20th century, names like "King" and "Prince" were disproportionately common among African Americans—with Black men being up to five times more likely to have these names than would be expected by their proportion in the population.

Historical Development of African American Names

Distinctive Naming Patterns Began Before Black Power

Research in 2004 documented a "dramatic rise in African-American names of various origins" coinciding with the 1960s civil rights movement, with the Black Power movement triggering "a change in black perceptions of their identity." Wiki

Economic historians found that distinctive Black naming patterns actually existed as early as the antebellum period (mid-1800s), with approximately 3% of Black Americans having distinctively Black names both before and after the Civil War. However, the specific names changed over time - names popular in the 19th century are completely different from those popular today.

The Royal Name Connection

During the Black Power movement of the 1960s-70s, there was a notable increase in names reflecting royalty, power, and nobility:

Names like King, Queen, Prince, Princess, Royal, Majesty, Duke, and Earl became more common

These names served as affirmations of dignity, status, and cultural pride

The adoption of such names reflected a conscious effort to reject names associated with the dominant white culture

Statistical Evidence

While precise statistics on the frequency of royal names specifically are limited, research has found:

Cook, Logan, and Parman's research identified historical African American names including "King" and "Prince" among the 17 distinctively Black male names in the early 20th century, where approximately 2% of Black men had one of these distinctive names. Nber Their research showed that a Black man in North Carolina was nearly four times more likely than a white man to have one of these distinctively Black names, while in Alabama the ratio was sixteen times higher.

The data showed that:

King: 57.1% of men with this name in the 1900 census were Black (when Blacks were only 11.6% of the population)

Prince: 78.1% of men with this name in the 1900 census were Black

These names were significantly more common among Black men than white men

Evolution During the Black Power Era

During the peak of the Black Power movement (late 1960s-early 1970s), many African Americans adopted names that emphasized their identity, reflecting a shift toward racial pride. Wikipedia This naming practice was part of a broader cultural transformation that included wearing African clothes, adopting "Afro" hairstyles, and embracing African cultural elements.

The practice extended beyond individual choices to organizations. For example, the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) allowed applicants to choose new names symbolizing their "New Afrikan" identities, with application forms including lines for both "Slave Name" and "Assumed Name." AAIHS

In contemporary times, these naming practices continue, with royal-style names like King, Queen, Princess, and Majesty remaining more common in African American communities than in other demographic groups.

African American naming practices during the Black Power era deliberately incorporated royal and honorific titles as a way to affirm dignity, identity, and cultural pride

During the 1960s-70s, the Black Power movement explicitly encouraged African Americans to show pride in their heritage through naming practices. This was a deliberate cultural statement against the legacy of slavery and oppression. The adoption of names like King, Queen, Prince, and Royal represented a conscious effort to reject names associated with subjugation and to assert dignity and self-worth.

These royal names have been significantly more common among African Americans than other demographic groups. Names like "King" and "Prince" were overwhelmingly more likely to be held by Black men in early 1900’s in America - with King being held by Black men at a rate nearly five times their proportion in the population.

The linguistic and cultural patterns we've traced across continents and millennia provide an interesting backdrop for understanding these naming practices. Just as ancient Egyptian concepts of divine kingship spread throughout the Mediterranean world, African Americans have used royal naming patterns as a way to preserve and celebrate cultural heritage despite historical disruptions. It may just be an African naming practice to name their children after the divine nature of their people.

Cultural Significance and Meaning

The adoption of royal names during the Black Power era had several cultural and social dimensions:

Assertion of Dignity and Worth These names served as a rejection of the historical degradation experienced during slavery and Jim Crow, symbolically elevating individuals above their socially assigned status.

Connection to African Heritage The "Afrocentrism movement that grew in popularity during the 1970s saw the advent of African names among African Americans, as well as names imagined to be 'African-sounding'." Wikipedia Though many royal names aren't specifically African in origin, they connected with the concept of African royalty and nobility.

Psychological Empowerment As noted by some who adopted this practice: "My ex-wife and I gave our children non-Western names (Imani, Dharma, Vilaschandra) to empower their Spirits." FamilyEducation The names were intended to instill pride and self-determination.

This naming tradition represents more than just linguistic preference - it's a cultural practice with deep connections to identity formation, historical consciousness, and resistance to racial oppression. The continued use of royal and honorific names in African American communities today reflects this ongoing cultural pattern.

Ancient Echoes: The "Ra/Re" Connection

What makes this naming tradition even more fascinating is how it may connect to much older patterns. The ancient Egyptian concept of "Ra"—the sun god and divine king—appears in countless words related to royalty, divinity, and power across multiple languages.

Consider how the "r" sound with various vowels creates words related to royalty and power:

"Ray/Re" (the sun and divinity)

"Royal/Rex/Regina" (kings and queens)

"Reign" (to rule)

This pattern isn't coincidental. The Egyptian pharaoh was seen as the living embodiment of Ra, the sun god, creating a direct connection between divinity and kingship that influenced cultures across Africa, the Mediterranean, and beyond.

When African Americans choose names like King or Queen, they may be unconsciously reconnecting with this ancient tradition that places royalty, divinity, and personal dignity at the center of identity.

Royal Heritage: How African American Names Like "King" Echo Ancient Traditions

In the tapestry of American culture, few threads are as vibrant and meaningful as the naming traditions within African American communities. Names like King, Queen, Prince, and Majesty are more than fashionable, they're powerful statements of identity that connect to recent civil rights history to much deeper cultural roots.

Resistance to Colonization: Ethiopia and Liberia

Among the dozens of African nations, only two fully resisted European colonization during the "Scramble for Africa" in the late 1800’s: Ethiopia and Liberia, each with its own unique story of maintaining independence.

Ethiopia's resistance is particularly noteworthy. When Italian forces invaded in 1896, their Emperor led Ethiopian forces to a decisive victory at the Battle of Adwa—the first time an African nation had defeated a European colonial power. This victory preserved Ethiopia's independence until the Italian occupation of 1936-1941 during the Second Italian-Ethiopian War (which was relatively brief compared to the colonial period experienced by other African nations).

Liberia followed a different path. Founded in 1822 by formerly enslaved Americans, it declared independence in 1847 as Africa's first republic.

Both nations maintained distinctive cultural practices, including preserving distinct language traditions, music, and naming practices.

Preserving Indigenous Languages: Ethiopia maintained Amharic and other indigenous languages as official and literary languages rather than adopting European ones.

Religious Continuity: Ethiopia held onto its Orthodox Christian tradition that dated back to the 300’s AD, maintaining religious practices distinct from European Christianity that evolved later.

Royal Lineage: Ethiopia's monarchy traced its lineage back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba from 970 BC, maintaining a sense of royal continuity from well before European contact (and before Greece or Rome started to form!).

Distinctive Music and Art Forms: Both nations preserved distinctive musical traditions, artistic practices, and cultural ceremonies that reinforced their cultural identity.

Naming Traditions: The maintenance of traditional naming practices that connected individuals to ancestral lineages, cultural values, and spiritual traditions.

Cultural elements served as active tools of resistance against cultural domination. By maintaining distinctive cultural practices, Ethiopia and Liberia preserved political independence and cultural sovereignty—the ability to define themselves according to their own traditions rather than adopting European models.

Cultural Preservation in the African Diaspora

This pattern of cultural preservation as resistance echoes powerfully in African American communities and throughout the African diaspora. Even when political and economic freedom was denied, cultural practices provided avenues for maintaining identity and dignity:

Music: The evolution of distinctive musical traditions from spirituals to blues, jazz, soul, and hip-hop served not just as entertainment but as vehicles for preserving cultural memory and expressing resistance.

Language Patterns: The development of distinctive speech patterns, dialects, and linguistic innovations that maintained connections to African language structures while adapting to new contexts.

Religious Practices: The adaptation of Christianity to include elements of African spiritual traditions, creating distinctive forms of worship that preserved important cultural values.

Naming Traditions: The persistence of naming patterns that affirmed dignity, royal heritage, and cultural identity even when these were actively denied by the dominant society.

These cultural practices weren't just passive remnants of African traditions but active strategies for maintaining identity and dignity in the face of oppression. They created spaces of cultural sovereignty even when political and economic freedom was denied, allowing communities to preserve and transmit values, memories, and traditions that might otherwise have been lost.

The Power of Naming

Names are never just labels. They're declarations of identity, hope, and heritage. The prevalence of royal names in African American communities reminds us that naming is perhaps our most fundamental act of self-determination.

When we understand the historical and cultural context of these names, we see them not as unusual or unique, but as meaningful continuations of a tradition that asserts dignity and power through language.

In a society still working to overcome its legacy of racial inequality, these royal names continue to serve as daily affirmations that every child deserves to be treated with the dignity of a king or queen.

The Unacknowledged Foundations

The magnitude of Africa's contributions to human civilization has been systematically underacknowledged, with perhaps the most profound example being the very alphabet we use to communicate. The evolution of writing systems that eventually gave rise to our modern alphabet began in Africa, with Egyptian hieroglyphics evolving into Proto-Sinaitic script, which then influenced Phoenician writing—the direct ancestor of Greek and later Roman alphabets.

This fundamental technology—the ability to record and transmit human thought across time and space—has African origins that are rarely centered in mainstream historical narratives. Instead, the story often begins with Greece or Rome, erasing the African foundations upon which these later civilizations built.

Even more striking is how Rome's vaunted "Golden Age" was fueled directly by African resources. Egypt's legendary grain harvests fed Rome's expanding population. African gold filled Roman treasuries. African intellectual traditions enhanced Roman culture. The glory Rome claimed for itself was substantially built upon African foundations—a historical reality that challenges conventional Eurocentric narratives.

Erased Contributions, Persistent Patterns

When we understand these historical dynamics, the persistence of royal naming patterns in African American communities takes on even deeper significance. These names don't just assert individual dignity—they implicitly challenge historical narratives that have minimized or erased African contributions to human civilization.

Names like King and Queen speak to a truth that persists despite centuries of attempted erasure: that African civilizations weren't peripheral to human development but central to it, that they weren't recipients of "civilization" but among its primary architects. These names carry echoes of a time when African kingdoms weren't just politically powerful but culturally influential, shaping the development of societies across the Mediterranean world and beyond.

The historical revisionism that positioned Rome as the originator rather than the beneficiary of numerous cultural and technological innovations didn't just distort our understanding of the past—it created false hierarchies that continue to influence how we value different cultural traditions today. Royal names in African American communities serve as linguistic resistance to these distortions, affirming connections to cultural traditions that preceded and informed European civilizations.

Beyond Appropriation to Acknowledgment

What's particularly striking about this history is how the appropriation of African knowledge, resources, and cultural innovations was paired with the denial of their origins. Rome didn't just benefit from Egyptian grain—it recast Egypt's achievements within its own imperial narrative. The alphabet wasn't just adopted from its African and Phoenician origins—its lineage was obscured to center European achievements.

This pattern of appropriation without acknowledgment created a distorted historical record that continues to shape contemporary understandings. When we fail to recognize that many "Western" innovations have African origins, we perpetuate a narrative that positions Africa as perpetually catching up to innovations that, in many cases, it helped pioneer.

Royal naming traditions remind us that cultural patterns persist even when their origins are denied or forgotten. They suggest that certain fundamental truths—about human dignity, about cultural achievement, about historical connections—cannot be completely erased, even by centuries of systematic distortion.

Christianity's African Roots

Perhaps one of the most profound examples of historical amnesia involves Christianity itself. The religion that would come to dominate Western civilization and be erroneously characterized as a "European" tradition has deep African and Middle Eastern roots that are frequently obscured in popular understanding.

Christianity emerged in the Middle East among Jewish communities and quickly spread throughout North Africa. Many of the earliest and most influential Christian theologians and leaders were African:

St. Augustine of Hippo, one of Christianity's most influential theologians, was North African

Tertullian, often called "the father of Western theology," was from Carthage in North Africa

The Desert Fathers and Mothers who pioneered Christian monasticism lived and practiced in the deserts of Egypt

Coptic Christianity in Egypt represents one of the oldest continuous Christian traditions in the world

Ethiopia adopted Christianity in the 4th century, making it one of the earliest Christian kingdoms

The early centers of Christian learning and development were not in Europe but in Alexandria, Antioch, and other African and Middle Eastern cities. The formative councils that defined core Christian doctrines took place largely in North Africa and the Middle East, with African theologians playing central roles in shaping what would become orthodox belief.

Furthermore, many of the spiritual practices associated with Christianity—from monasticism to certain forms of prayer and contemplation—were pioneered in African contexts before spreading to Europe. The desert traditions of Egypt and Ethiopia profoundly influenced how Christianity would be practiced throughout the world.

This African foundation of Christianity adds another dimension to understanding the significance of royal names in African American communities. Names that evoke dignity, royalty, and divine connection reflect not just general human aspirations but specific African traditions of spirituality and leadership that helped shape Christianity itself.

Names as Vehicles of Cultural Memory

In this context, the prevalence of royal names like King and Queen in African American communities takes on even deeper significance. These names didn't just assert individual dignity—they participated in a broader pattern of cultural preservation that has characterized both independent African nations and diaspora communities.

Just as Ethiopia maintained its royal traditions as a form of resistance against European domination, African Americans preserved naming patterns that connected them to concepts of royalty and dignity even when their political and economic rights were severely restricted. These names became vehicles of cultural memory, carrying forward concepts and values that the dominant society actively sought to suppress.

The persistence of these naming patterns across generations suggests something profound about cultural resistance—that even in the most adverse conditions, people find ways to preserve and transmit the elements of identity they consider most essential. Names become containers of cultural memory, carrying forward values and traditions even when other forms of cultural expression are restricted.

This understanding enriches our appreciation of African American naming traditions. They represent not just individual choices but participation in a centuries-long tradition of cultural preservation as resistance—a tradition shared with the few African nations that successfully maintained their political independence and with diaspora communities throughout the Americas.

In reclaiming and celebrating these naming traditions, we acknowledge not just their aesthetic or personal significance but their role in a larger story of cultural resilience and resistance. We recognize that cultural sovereignty—the ability to name oneself and one's children according to one's own traditions rather than adopting those of the dominant society—is itself a profound form of freedom that persists even when other freedoms are denied.

The royal names that continue to appear with greater frequency in African American communities aren't just individual expressions but part of this collective tradition of cultural preservation—living testaments to how communities have maintained dignity and identity even in the face of systematic attempts to erase them.

Reclaiming a Stolen Legacy

The disparagement of African heritage wasn't based on objective inferiority, but was constructed to justify exploitation – theft of lands and resources and people. They were diminished because of their power, not due to lack of it.

Rome coveted Egypt's gold, grain, and glory. European powers needed to construct narratives that diminished African civilizations to rationalize their actions. This systematic devaluation of African contributions to human civilization served political and economic purposes, not historical truth.

As we gain greater access to information and scholarship becomes more inclusive, we're beginning to see more clearly how distinctly African many cultural traditions are. The persistence of royal naming traditions might be one small but meaningful thread in this larger tapestry of cultural continuity.

The story of African American naming traditions cannot be separated from the larger tragedy of forced displacement and cultural erasure. Historical accounts document heart-wrenching stories of African royalty—princes and princesses playing on their homeland beaches—suddenly kidnapped and transported across the Atlantic to be enslaved. These weren't just isolated incidents but part of a systematic uprooting that severed millions from their heritage, titles, and identities.

For many African Americans today, ancestry remains an incomplete puzzle with missing pieces—family trees that abruptly stop at plantation records or ship manifests rather than tracing back to their true origins. The royal names that emerged in African American communities might be understood not just as aspirational but as reclamations of what was violently taken away.

In our modern era of increased information access and growing cultural awareness, we have an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider these historical narratives and recognize the richness of African cultural traditions that have persisted despite centuries of attempted erasure. Perhaps in these names – King, Queen, Royal – we can glimpse not just resistance to oppression, but the endurance of ancient wisdom that honors the inherent dignity in every human being.

These historical realities transform how we understand cultural patterns that persist in African American communities. When royal names like King and Queen appear with greater frequency among African Americans, they connect not just to general concepts of dignity but to specific historical traditions in which African leadership, wisdom, and spiritual insight played central roles in shaping human civilization.

The recovery of these historical truths isn't just about setting the record straight—it's about creating a more accurate foundation for understanding our present and imagining our future. When we recognize Africa's central role in human development, from the emergence of our species to the creation of fundamental technologies, spiritual traditions, and cultural patterns, we challenge narratives that have positioned certain peoples as inherently more innovative or civilized than others.

Names like King and Queen participate in this reclamation, asserting connections to royal and spiritual traditions that existed long before European contact and challenging the historical amnesia that has obscured Africa's contributions. They remind us that dignity isn't something bestowed by dominant cultures but something inherent in human identity—a truth that African civilizations recognized and celebrated for millennia before their encounters with European powers.

In acknowledging these connections, we aren't diminishing any culture's achievements but completing our understanding of how human innovation has always been a collaborative enterprise, building on shared knowledge that crosses geographical and cultural boundaries. We're recognizing that the story of human civilization, including our religious and spiritual traditions, isn't a story of separate, competing cultures but of continuous exchange and mutual influence—a story in which African innovations and wisdom played a foundational role that has too often gone unacknowledged.

The royal names that persist in African American communities aren't just assertions of individual dignity—they're threads connecting present identity to this more complete historical understanding, challenging us to recognize not just the trauma of displacement and oppression but the grandeur and influence of the civilizations from which those who were enslaved were torn.

In this light, names like King and Queen can be understood not just as aspirational but as declarative—statements of connection to royal and spiritual legacies that shaped human history long before the disruptions of colonialism and slavery, legacies whose influence continues to resonate in ways we're only beginning to fully acknowledge.

Beyond Narratives of Mere Survival

The predominant narrative of African American history often begins with enslavement, as if nothing existed before the Middle Passage. This starting point doesn't just omit crucial chapters—it fundamentally distorts our understanding of African American identity and potential.

Before there were slaves, there were kings and queens, scholars and artisans, spiritual leaders and community builders. Ancient African civilizations produced mathematical innovations, architectural marvels, sophisticated systems of governance, and rich spiritual traditions. Names like King and Queen connect to this deeper heritage—one that existed long before European contact and continued to evolve despite attempts to erase it.

The preference for royal names in African American communities reflects an intuitive understanding that their story didn't begin with bondage but with dignity and agency. These names serve as linguistic anchors to a more complete history, one that acknowledges both the trauma of enslavement and the glory that preceded it.

Persistent Inequalities and Their Remedies

The burden of historical trauma continues to manifest in stark disparities today. African Americans face disproportionate challenges in nutrition, education, environmental justice, healthcare, and countless other measures of wellbeing. The casual dismissal of "Black Lives Matter" as somehow controversial rather than self-evident reveals how deeply ingrained these inequities remain.

Addressing these disparities requires more than acknowledgment of present injustice—it demands a fundamental reframing of historical understanding. When children learn about African and African American history primarily through the lens of victimhood rather than achievement, they absorb limiting narratives about their own potential. Every child deserves to see themselves reflected in stories of greatness, innovation, and leadership.

This isn't about denying the reality of historical oppression but about placing it in proper context—as a disruption of thriving civilizations rather than the beginning of the story. Royal names serve as small but significant threads connecting present identity to this more complete historical tapestry.

A Shared Human Story

The recognition that all humans trace their origins to Africa transforms how we understand these cultural connections. These aren't just important patterns for African Americans to reclaim—they're part of our collective human heritage. When we acknowledge Africa as the cradle of human existence and as a fountainhead of culture, we recognize that African wisdom and traditions aren't peripheral but central to human development.

The cultural amnesia that followed Rome's systematic destruction of earlier knowledge wasn't just a loss for specific communities but for humanity as a whole. We all inherit a historical narrative that was selectively curated by those in power, one that elevated certain contributions while minimizing or erasing others. Recovering these lost chapters benefits everyone, restoring a more accurate and complete understanding of our shared journey.

Breaking Cycles of Disadvantage

The practical implications of this historical reclamation are profound. Children thrive when they see themselves reflected in stories of achievement and possibility. By recognizing the royal heritage that names like King and Queen represent, we offer children powerful counter-narratives to the limitations society might place on them.

Supporting communities that have faced historical marginalization isn't just morally right—it's pragmatically essential for our collective future. Today's children will be tomorrow's leaders, innovators, and caretakers. Their wellbeing is inextricably linked to our own, making investment in their development not just ethical but practical.

The persistence of racism isn't just harmful to its targets—it diminishes us all, constraining human potential and perpetuating cycles of disadvantage that ultimately affect every segment of society. Recognizing our shared humanity and shared origins offers a path beyond these artificial divisions.

A New Chapter of Remembrance

Perhaps we stand at a unique moment in human history—one where technology, scholarship, and evolving consciousness converge to make possible a more complete understanding of our past. The digital age has democratized knowledge in unprecedented ways, allowing marginalized voices to challenge dominant narratives and recover histories that were systematically suppressed.

Names like King and Queen might be understood as small but significant threads in this larger tapestry of reclamation—linguistic artifacts that preserved something essential even when explicit knowledge was lost. They remind us that cultural memory persists in ways that transcend written records, that dignity can assert itself even when actively denied, that human identity remains resilient beyond measure.

In honoring the significance of these naming traditions, we take one small step toward a more complete understanding of our collective past and a more inclusive vision of our shared future. We recognize that the story of humanity isn't the story of some humans, but of all of us—connected by common origins, common struggles, and a common destiny that transcends the artificial boundaries we've too often allowed to divide us.

The royal heritage echoed in these names isn't just a matter of historical interest—it's a living legacy that continues to shape identities, inspire resistance to oppression, and affirm the inherent dignity of those who have too often been denied it. In acknowledging this legacy, we contribute to a more truthful accounting of our shared human journey and the diverse brilliance that has illuminated it from the beginning.

Africa: The Cradle of Humanity and Culture

It's now widely accepted that all humans trace their origins to Africa. The evidence from archaeology, genetics, and paleontology has established Africa as the birthplace of our species. Yet we've been much slower to recognize how much of human culture also has African origins.

The linguistic patterns that spread throughout the Mediterranean world, the mathematical concepts that underpin modern science, agricultural techniques that fed ancient civilizations, and philosophical ideas about governance and spirituality – all have deep roots in African soil. Names that evoke royalty and divinity may be one small but significant thread in this vast tapestry of cultural inheritance.

As our understanding of history becomes more inclusive and less Eurocentric, we're beginning to appreciate the full scope of Africa's contributions to human civilization. The naming traditions that persist in African American communities might be seen as living artifacts of this ancient heritage – cultural memories that have endured despite centuries of attempted erasure.

In recognizing the profound significance of these naming patterns, we glimpse a larger truth: that human innovation, wisdom, and dignity have always flowed from the continent where our species first emerged. The royal names that remain distinctive in African American communities today may be echoes of this original source – not just of our physical existence, but of our cultural identity as well.

In this light, names like King, Queen, and Royal aren't just assertions of dignity in the face of oppression – they're reclamations of a cultural birthright that belongs to all humanity but has special resonance for those whose ancestors were forcibly disconnected from their African origins.

The Unconscious Power of Ancient Sounds

What's particularly fascinating about these naming patterns is how they often seem to emerge without conscious historical knowledge. The "Ra/Re" sound pattern appears across countless languages and cultures, consistently associated with concepts of royalty, divinity, and power. Similarly, African American communities gravitated toward royal names without necessarily knowing their deeper historical resonance.

This raises a profound question: Do certain sounds and syllables carry inherent power that resonates with us on a subconscious level? The persistence of these patterns across time and geography suggests they might.

Consider how:

The "Ra/Re" sound appears in words related to royalty and power across dozens of unrelated languages

Royal naming patterns emerged in African American communities even when direct knowledge of African royal traditions had been systematically suppressed

Similar patterns of dignified naming appeared independently in various African diaspora communities across the Americas

These parallels suggest something deeper than coincidence—perhaps certain sound combinations trigger neurological or psychological responses that feel inherently powerful or dignified to the human ear.

Cultural Memory Beyond Conscious Knowledge

This phenomenon could be explained in several ways:

Deep Cultural Memory: Perhaps cultural knowledge persists in ways that transcend conscious understanding, passed down through subtle patterns of language and behavior even when explicit knowledge is lost.

Universal Sound Symbolism: Certain sounds might naturally evoke particular feelings or concepts across human cultures—what linguists call "sound symbolism."

Convergent Cultural Evolution: Similar naming practices might emerge independently in response to similar social conditions, particularly among people seeking to affirm dignity in the face of oppression.

Whatever the explanation, these naming patterns reveal something remarkable about human culture: important concepts and traditions can persist even when their origins are forgotten. The syllables themselves become vessels of meaning and power, carrying cultural significance across generations without conscious intention.

Reclaiming with or without Knowledge

What makes this particularly meaningful is that many of these naming choices weren't made with full knowledge of their historical connections. African Americans choosing royal names in the 1960s and 70s were often acting from an intuitive sense of what would confer dignity and power, rather than from conscious knowledge of ancient African royal traditions.

Yet this doesn't diminish the significance of these choices—if anything, it enhances it. It suggests that cultural memory can operate on levels deeper than conscious knowledge, that certain patterns of sound and meaning remain powerful even when their origins are obscured.

In this light, the prevalence of royal names in African American communities isn't just a political statement or a fashion trend, but a manifestation of cultural continuity that transcends the ruptures of history. These names carry power precisely because they tap into something deeper than what we consciously know—connecting to patterns of sound and meaning that have signified dignity and importance for thousands of years.

The Power Beyond Understanding

Perhaps there's wisdom in recognizing that not all cultural significance requires conscious understanding. The power of certain sounds, words, and names can be felt even when their histories aren't fully known. The gravitational pull toward royal and dignified names among people who have faced historical indignities may reflect an intuitive reaching toward what feels inherently powerful and affirming.

In a world where so much knowledge has been lost, suppressed, or fragmented, these intuitive connections become all the more significant. They suggest that human culture has resilience beyond what can be documented in books or taught explicitly—that some patterns of meaning persist simply because they resonate with something fundamental about how we experience language and identity.

African American naming traditions remind us that cultural reclamation doesn't always require complete historical knowledge. Sometimes, it begins with an intuitive sense of what feels right, what confers dignity, what sounds powerful. The conscious understanding—the historical connections and linguistic patterns—can be rediscovered later, affirming choices that were initially made from a place of intuition rather than explicit knowledge.

In this sense, names like King, Queen, and Royal aren't just echoes of ancient traditions—they're evidence of how cultural power persists even when its origins are forgotten, how certain sounds and meanings continue to resonate across millennia, how dignity can be reclaimed even when the full history of that dignity has been obscured.

Love as the Path to Recognition

Perhaps the most profound insight here is that understanding these cultural connections requires opening our hearts as much as our minds. It is love—love of humanity in all its diversity, love of truth beyond our comfortable narratives, love that transcends the boundaries of our own experience—that allows us to recognize these deeper patterns of human connection.

When we approach history and culture with love rather than fear or prejudice, we begin to see connections that were previously invisible. We become willing to consider that wisdom and beauty have flowed from sources we may have been taught to dismiss or ignore. We open ourselves to the possibility that cultural patterns once deemed "primitive" or "superstitious" might contain profound insights about human identity and dignity.

The persistence of royal names in African American communities isn't just a cultural curiosity—it's a testament to how human dignity asserts itself even in the most adverse conditions. These naming patterns remind us that all people intuitively reach for symbols of worth and value, that the desire to be recognized as inherently royal—as deserving of dignity and respect—is fundamental to the human spirit.

In recognizing this shared humanity, we begin to put aside the fears and prejudices that have too often divided us. We see that cultural differences aren't threats but treasures, that the diversity of human expression enriches rather than diminishes our collective experience. And we understand that acknowledging the African origins of many cultural patterns isn't about diminishing other traditions but about completing our picture of human heritage.

A Future Built on Understanding

As we move forward, perhaps the most powerful legacy of these naming traditions isn't just what they tell us about the past, but what they suggest about our future. They remind us that human culture is resilient beyond measure, that dignity can be asserted even when it's denied, and that love—love of heritage, love of identity, love of humanity in all its forms—provides the foundation for genuine understanding.

In a world still struggling with division and prejudice, these ancient patterns of sound and meaning offer a gentle reminder: we are more connected than we know, our histories more intertwined than we've been taught, our future more shared than we sometimes imagine. And it is love—love that compels us to look beyond our fears and preconceptions—that will ultimately reveal these connections in their full and beautiful complexity.

Names like King and Queen aren't just assertions of identity in the present—they're echoes from our shared past and pointers toward a future where all human dignity is recognized and celebrated. In understanding their significance, we take one small but meaningful step toward that future.

Timeline: Royal Naming Traditions and Cultural Memory in Africa and the Diaspora

The timeline covers:

Ancient royal naming traditions across various African kingdoms (Egypt, Kush, Axum, West African empires)

The disruption caused by slavery and colonization - how naming practices were systematically targeted as part of cultural erasure

The persistence of royal names despite these pressures - including research showing names like "King" and "Prince" remained disproportionately common among African Americans

The conscious reclamation of royal naming traditions during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements

Contemporary significance of these naming patterns as forms of cultural memory and resistance

“Scientific” explanations used to perpetuate slavery

Naming practices became even more significant as acts of resistance against a comprehensive system that used "science" to dehumanize African peoples and deny their royal heritage. The persistence of royal names despite this systematic assault demonstrates their profound importance as vessels of cultural memory and dignity.

Ancient Periods: Royal Naming Traditions Emerge

3100-332 BCE: Ancient Egypt

Pharaohs used titles like Nesu (King), Nesut (Royal Woman), and Hemet Nesut (King's Wife)

Royal names often included elements like Ra (sun god) and Amen/Amun (hidden god)

Common naming practice included titling children with royal elements: Malik (King), Malika (Queen)

Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions show names of regular citizens incorporating royal elements as a way to connect to divine power

1000 BCE-1000 CE: Kingdom of Kush/Nubia

Rulers used the title Kandake/Candace (Queen Mother/Queen Regent)

Notable example: Kandake Amanirenas who successfully fought against Roman expansion

Children were often named after royal ancestors to maintain lineage connections

The title Qore (King) also appeared in personal names

300 BCE-700 CE: Axumite Empire (Modern Ethiopia)

Kings used the title Negus (King)

The highest title was Negusa Nagast (King of Kings)

Personal names often incorporated Selassie (Trinity) and Haile (Power)

Example: Later emperor Haile Selassie whose birth name was Tafari Makonnen

700-1600 CE: West African Kingdoms

Ghana Empire: Rulers used the title Kaya Maghan (King of Gold)

Mali Empire: Mansa (King/Emperor) became a personal name element

Songhai Empire: Sonni and Askia (royal titles) became part of naming traditions

Kingdom of Benin: The Oba (King) title influenced naming patterns

Medieval to Early Modern Period: Cultural Exchange and Preservation

1200-1500: Swahili Coast Kingdoms

Title Sultan adopted from Arabic influences while maintaining African naming elements

Personal names began to blend African and Arabic traditions: Sultan Alwali

Names incorporating Mtemi (Chief/King) remained common

1350-1800: Kingdom of Kongo

Title Mwene (Lord/King) influenced personal naming

After Portuguese contact, royal naming incorporated Catholic elements while maintaining African roots

King Afonso I (born Nzinga Mbemba) exemplifies this hybrid naming

1400-1800: Kingdom of Dahomey

Royal title Dokouno (King) appears in personal names

Women with royal connections used Kpojito (Queen Mother) elements in naming

Names incorporated elements like Dada (King) and Hwanjile (Queen)

Colonial Era: Disruption of Naming Traditions and Scientific Racism

1500-1700: Early Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

Enslaved Africans systematically stripped of birth names upon arrival in Americas

Slave traders and owners imposed European names, erasing cultural connections

First major disruption: Transition from meaningful African names to imposed European names

Some enslaved people maintained secret "day names" or hidden African names within families

1700-1800: Height of Atlantic Slave Trade

African naming traditions severely disrupted across the diaspora

Colonial authorities in Africa began imposing European names in official documents

Children increasingly given Christian/European names, with African names becoming secondary

In some regions, speaking African languages (including names) prohibited or discouraged

Documented cases of enslaved people risking punishment to maintain traditional naming practices

1800-1884: Pre-"Scramble for Africa"

Missionary education further eroded traditional naming practices

Colonial records often refused to recognize African names, forcing adoption of European ones

Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855-1868) insisted on maintaining traditional naming despite European pressure

Liberian settlers brought American naming practices back to Africa, creating hybrid traditions

1800-1900: Scientific Racism and the Justification of Oppression

Emergence of "scientific racism" to justify enslavement and colonization

1839: Samuel Morton publishes "Crania Americana," attempting to prove racial hierarchy through skull measurements

1854: Josiah Nott and George Gliddon's "Types of Mankind" furthers racist pseudoscience

1869: Francis Galton coins the term "eugenics," launching movement to "improve" human race through selective breeding

These theories falsely positioned Africans as inherently inferior, providing justification for:

Continued enslavement and later segregation

Denial of voting rights and education

Medical experimentation without consent

Erasure of African cultural achievements and royal heritage

African royal titles and dignified names deliberately suppressed as contradicting the narrative of inherent inferiority

1884-1957: Colonial Rule Across Africa

Berlin Conference divides Africa among European powers

Colonial administrations systematically suppressed traditional naming practices:

Belgian Congo: Official documentation required Christian/European names

British colonies: "Native" names often recorded incorrectly or replaced with English equivalents

French colonies: Policy of "assimilation" actively discouraged traditional naming

Exception: Ethiopia after 1941 maintained traditional naming as form of resistance

Early freedom movements begin reclaiming African names as political statements

Resistance and Reclamation

1800-1900: Hidden Resistance in the Americas

Despite official European naming, evidence shows African Americans continued to use royal-inspired names:

Research by Cook, Logan, and Parman found names like King and Prince disproportionately common among African Americans

Names like Queen, Royal, and Noble appear in historical records

Post-emancipation records show increased use of traditionally African naming patterns

Freedmen sometimes chose new names to represent dignity: Freeman, Justice, Noble

1900-1960: Eugenics, Segregation and Early Civil Rights Era

1907-1937: Eugenics movement reaches peak in America:

32 states pass forced sterilization laws primarily targeting Black and indigenous women

1927: Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell upholds forced sterilization

American eugenics programs later inspire Nazi racial policies

Eugenics movement teaches that African Americans are genetically inferior, specifically attacking:

African intelligence and capability for self-governance

African cultural achievements including royal traditions

African naming practices as "primitive" compared to European names

Jim Crow segregation reinforces social hierarchy allegedly "proven" by eugenics

Despite this oppression:

Names emphasizing dignity become more common in African American communities

Marcus Garvey's Pan-African movement (1920s) encourages pride in African heritage

Early examples of African Americans reclaiming African names (though still limited)

Continued disproportionate use of names like King, Queen, Prince in African American communities

1960-1980: Black Power Movement and Countering Scientific Racism

Dramatic increase in African and royal-inspired naming in African American communities

Notable examples:

Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) reclaims African name

Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) adopts name honoring African leaders

Names like Malik (King) and other royal titles become increasingly popular

Active resistance against scientific racism and eugenics:

Black scholars and activists challenge pseudoscientific racial hierarchies

1968: Association of Black Psychologists formed to counter racist psychological theories

1972: Revelation of Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972) exposes medical racism

Growing academic work reestablishing Africa's historical contributions to civilization

African independence movements inspire naming practices honoring pre-colonial traditions

Names become explicit political statements of identity and resistance against generations of scientific dehumanization

1980-Present: Contemporary Renaissance

African Americans increasingly give children names reflecting royal heritage

Names like King, Queen, Royal, Messiah, Prince, and Princess show statistical prominence

2000s data shows names like King among top 200 names for African American boys

Research shows that "royal" names remain statistically more common in African American naming practices

Cultural renaissance expands to embrace wider range of African naming traditions

Contemporary Analysis: Patterns and Significance

Cultural Memory Despite Disruption

Despite centuries of attempted erasure, royal naming patterns persist

Statistical analysis shows consistent patterns of dignified/royal naming across generations

Suggests deep cultural memory operates beyond conscious historical knowledge

Names serve as vessels of cultural continuity even when other traditions disrupted

Geographic Distribution

Royal naming patterns appear across African diaspora communities (U.S., Caribbean, Latin America)

Similar patterns emerge independently in separated communities

Suggests fundamental cultural pattern rather than coincidental trend

Linguistic Analysis

Royal naming elements show phonetic similarities across diverse African languages

Sound patterns (especially the "Ra/Re" sound) appear consistently in royal contexts

Royal naming practices show remarkable resilience despite linguistic disruptions

Contemporary Significance

Royal names continue to serve as assertions of dignity and cultural heritage

Naming practices represent one of the most enduring forms of cultural resistance

Contemporary reclamation of royal naming connects present identity to ancestral dignity

Names serve as daily reminders of heritage beyond the narratives of enslavement and colonization

Royal names actively counter centuries of scientific racism that attempted to erase African dignity:

Rejecting eugenicist hierarchies that denied African humanity

Asserting dignity in the face of historical dehumanization

Reconnecting with royal and dignified traditions that racist pseudoscience attempted to obscure

Creating counter-narratives to the lingering effects of scientific racism in contemporary society

This timeline illustrates how naming practices reflect broader patterns of cultural continuity, disruption, and reclamation. Despite systematic attempts to sever African peoples from their heritage through enslavement, colonization, and pseudoscientific racism, certain fundamental patterns—particularly those related to dignity and royal identity—have persisted across generations and geographic boundaries.

The scientific establishment's role in justifying oppression cannot be overstated. For over a century, respected Western scientists produced "research" claiming to prove African inferiority, directly attacking the notion that Africans had ever created sophisticated civilizations or held royal status. This pseudoscience deliberately obscured Africa's rich royal traditions while justifying the continued subjugation of African peoples across the diaspora.

Against this comprehensive assault on African dignity, the continued prominence of royal names in African American communities represents a profound form of resistance. These names aren't just a modern fashion but part of a long tradition of maintaining cultural memory and asserting human dignity even in the face of scientific, political, and social attempts to erase it.

Noting specific “Scientific” theories that promoted racism:

Scientific Racism (1800-1900) - How figures like Samuel Morton, Josiah Nott, and George Gliddon created pseudo-scientific theories claiming to "prove" racial hierarchies, directly undermining recognition of African royal traditions

The Eugenics Movement (1900-1960) - The American eugenics movement that:

Led to forced sterilization laws targeting Black Americans

Claimed genetic inferiority of African people

Later inspired Nazi racial policies

Specifically attacked and undermined African cultural and royal traditions

Resistance to Scientific Racism (1960-1980) - How the Black Power movement actively fought against scientific racism by:

Forming organizations like the Association of Black Psychologists

Exposing medical racism like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Reclaiming African names as direct resistance to racist pseudoscience

Contemporary Significance - How royal names today serve as a powerful counter to the lingering effects of scientific racism by asserting dignity and reconnecting with traditions that racist pseudoscience attempted to obscure

These additions highlight how naming practices became even more significant as acts of resistance against a comprehensive system that used "science" to dehumanize African peoples and deny their royal heritage. The persistence of royal names despite this systematic assault demonstrates their profound importance as vessels of cultural memory and dignity.